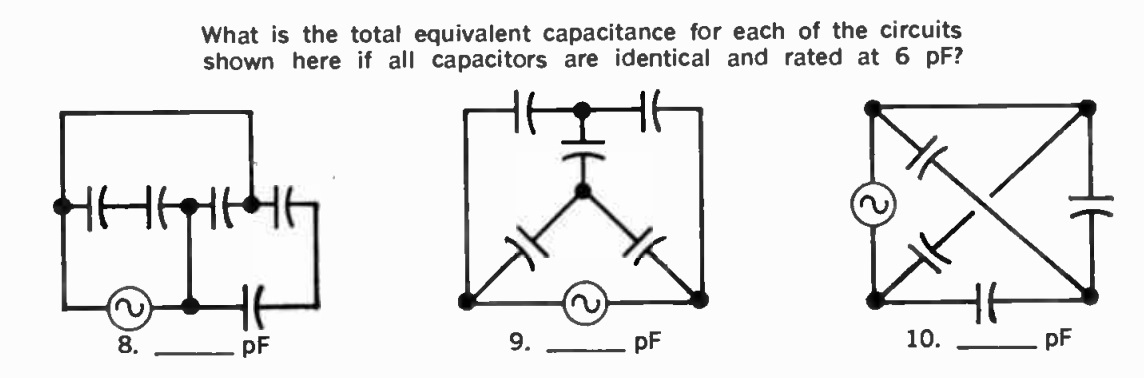

This quiz appeared in Popular Electronics 50 years ago this month, January 1971. With a little bit of re-drawing and some basic math, you should be able to come up with the answers. If not, we’ll post them here tomorrow.

This quiz appeared in Popular Electronics 50 years ago this month, January 1971. With a little bit of re-drawing and some basic math, you should be able to come up with the answers. If not, we’ll post them here tomorrow.

This quiz appeared in Popular Electronics 50 years ago this month, January 1971. With a little bit of re-drawing and some basic math, you should be able to come up with the answers. If not, we’ll post them here tomorrow.

This quiz appeared in Popular Electronics 50 years ago this month, January 1971. With a little bit of re-drawing and some basic math, you should be able to come up with the answers. If not, we’ll post them here tomorrow.

Sixty years ago this month, the January 1961 issue of Electronics Illustrated showed this automotive record player, the Norelco “Auto Mignon” (sold in Europe under the Philips name).

Sixty years ago this month, the January 1961 issue of Electronics Illustrated showed this automotive record player, the Norelco “Auto Mignon” (sold in Europe under the Philips name).

The set played 45 RPM records, which were loaded from the front with a “trap door,” not unlike how CD’s are loaded into most car players. The set played through the car radio, and ran off either 6 or12 volts. It retailed for $57.50

You can see a well preserved specimen of the model in this video:

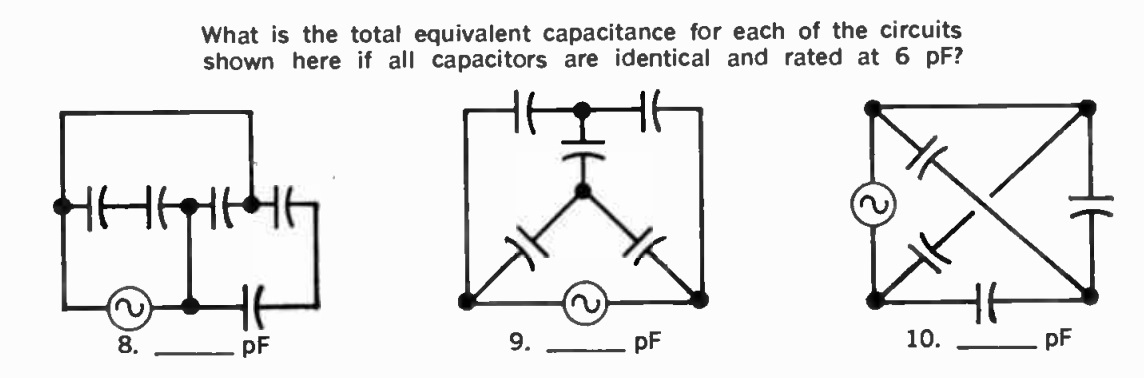

Shown here as it appeared 80 years ago is the service shop of Sam Tagart, who had recently moved his shop to this fine modern store at 37th & W. North Avenue, Milwaukee.

Shown here as it appeared 80 years ago is the service shop of Sam Tagart, who had recently moved his shop to this fine modern store at 37th & W. North Avenue, Milwaukee.

The move to a prime location was made possible by direct mail advertising. The January 1941 issue of Radio Service Dealer reported that Tagart started out by mailing 250 direct mail ads four times per year to radio set owners, along with occasional mailings to radio dealers. At first, he got a return of about 10%, which worked its way up to 20%. He had recently increased his mailings to 1200 each time.

Part of his success was the spic-and-span shop shown here. He worked on sets in view of his customers, and many regular customers came from those who watched him work. Above his workbench is a mirror, which allows him to easily keep an eye on the front of the store.

The building that housed Tagart’s shop is no longer standing, but the building next door is. There’s now a Citgo gas station where that shop once stood:

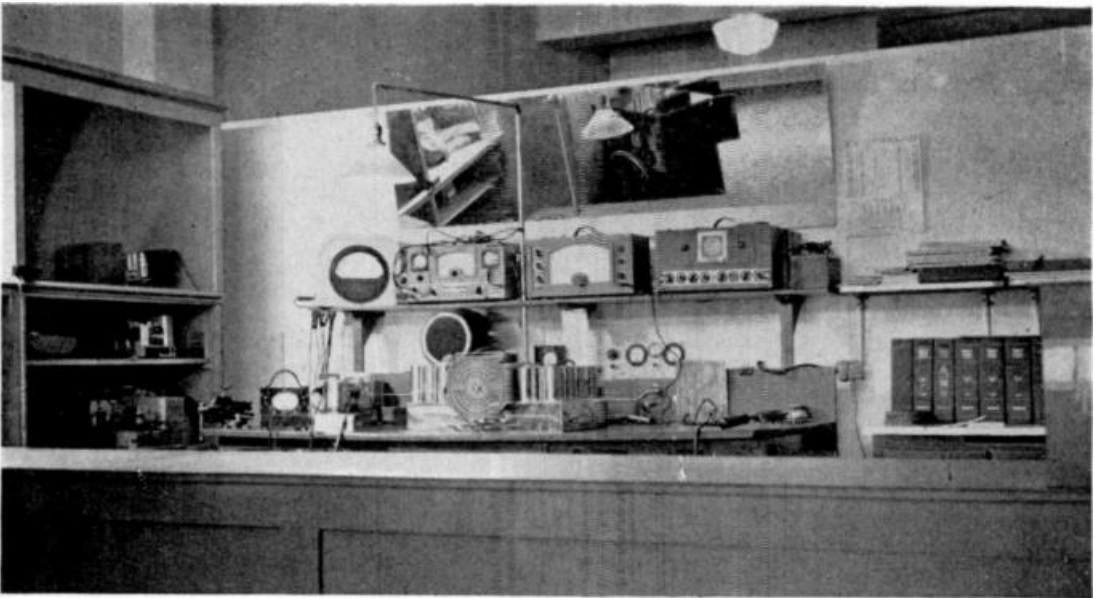

This utilitarian-looking receiver appeared fifty years ago this month in the January 1971 issue of the British Radio Constructor magazine. Complete with its own coat of arms, the set was dubbed the Crusader, and tuned longwave (150-375 kHz), mediumwave (545-1546 kHz), and shortwave (1.85-18.75 MHz). Even though it was billed as being for the near beginner, the 6-tube set was a superheterodyne, and probably did an admirable job of pulling in the weak stations. Construction was simplified by the pre-assembled coil pack, which is undoubtedly unobtainium today. It featured a transformer power supply, making it a safe set to operate from the AC mains.

This utilitarian-looking receiver appeared fifty years ago this month in the January 1971 issue of the British Radio Constructor magazine. Complete with its own coat of arms, the set was dubbed the Crusader, and tuned longwave (150-375 kHz), mediumwave (545-1546 kHz), and shortwave (1.85-18.75 MHz). Even though it was billed as being for the near beginner, the 6-tube set was a superheterodyne, and probably did an admirable job of pulling in the weak stations. Construction was simplified by the pre-assembled coil pack, which is undoubtedly unobtainium today. It featured a transformer power supply, making it a safe set to operate from the AC mains.

If Junior is looking for a science fair project, the teacher probably wants the students to create an experiment to answer some question. Often, the student is required to submit the question for approval. If the teacher deems the question to be appropriate, then the students are allowed to proceed with the experiment.

If Junior is looking for a science fair project, the teacher probably wants the students to create an experiment to answer some question. Often, the student is required to submit the question for approval. If the teacher deems the question to be appropriate, then the students are allowed to proceed with the experiment.

Occasionally, teachers have been known to be nitpicky with this process, rejecting questions based upon their personal perception of scientific merit. Therefore, there might be some advantage to proposing a question that the teacher doesn’t understand. Then, they can’t reject the question without revealing their own scientific ignorance.

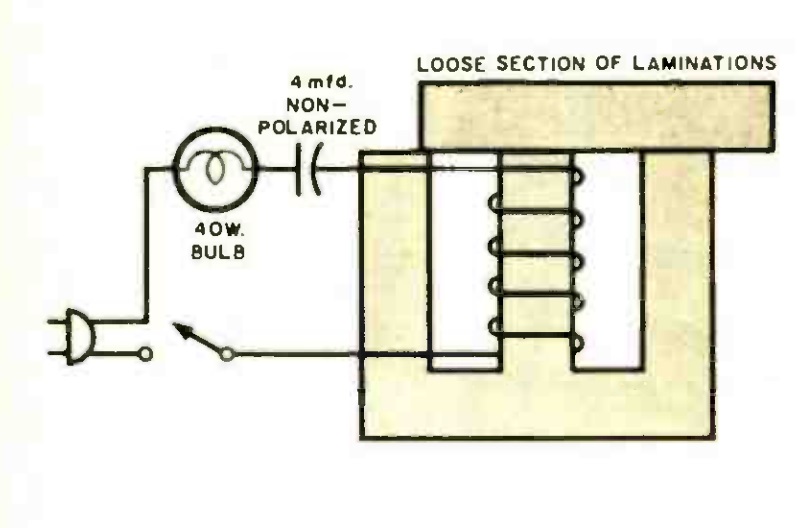

We can guarantee that Junior’s teacher has never heard of ferroresonance. Therefore, if Junior proposes a project involving ferroresonance, then the teacher is bound to accept. Junior’s question could be something along the lines of: “Can non-linear inductance be used to make a ferroresonant relaxation oscillator?” It turns out that the answer is yes, according to the January 1961 issue of Popular Electronics, and it can be proven by the experiment shown here.

M. Boucherot. Image courtesy of École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la Ville de Paris.

Ferroresonance was first described in 1907 by French electrical engineer Joseph Bethenod, and named by French engineer Paul Boucherot.

A circuit is resonant when the capacitive reactance and inductive reactance are equal. And normally, the reactance is dependent upon the frequency alone. But other factors, such as magnetic flux of the inductor, can cause non-linear effects at the time when the circuit is initially switched on.

The heart of this experiment is an old choke of more than 1 Henry, capable of handling at least 50 mA. I’m guessing that one could use an old power transformer. Remove the frame to reveal the “E” shaped core inside. From another old transformer, obtain a section of laminations, which will be laid on the top.

According to the magazine, “the point of adjustment is quite critical and requires a bit of patience.” The loose section starts completely on top of the “E”. With the switch on, the bulb should not light. That section is slowly moved, about 1/32 of an inch at a time, with the switch turned off after each move. At the critical point, the bulb will flash on and off at intervals of about 1 second.

Junior will thus have demonstrated that by varying the magnetic flux, he has introduced a non-linearity which causes the circuit to flash.

It should be noted that this experiment involves 120 volt electrical current, so proper precautions should be taken.

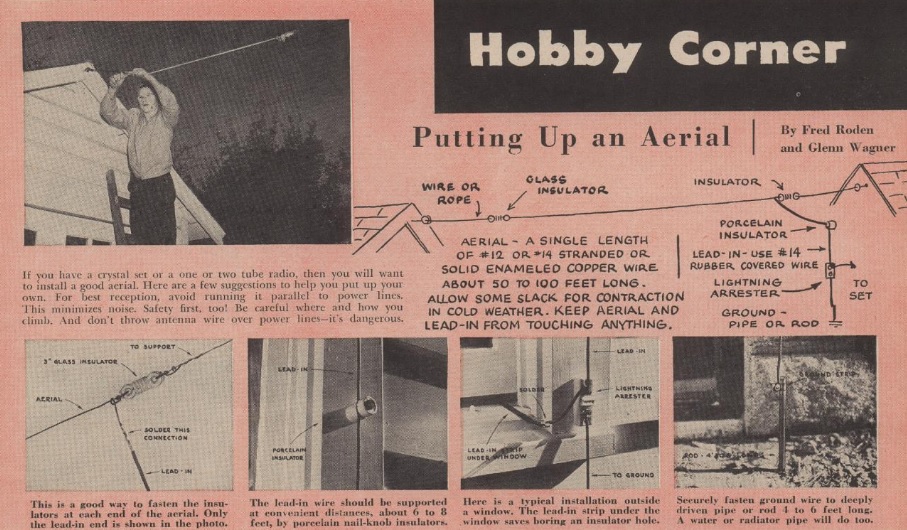

Seventy years ago, it was a pretty good bet that a Boy Scout would have an interest in radio, so the “Hobby Corner” feature of Boys’ Life, January 1951, offered some pointers for a Scout on how to up an aerial.

Seventy years ago, it was a pretty good bet that a Boy Scout would have an interest in radio, so the “Hobby Corner” feature of Boys’ Life, January 1951, offered some pointers for a Scout on how to up an aerial.

The magazine noted that if you had a crystal set or a one-tube radio, then a good antenna would ensure good reception. It recommended a run of about 50-100 feet of copper wire, with glass insulators carefully placed at either end. Because the wire would contract in cold weather, some slack was called for. To avoid noise, the antenna should not be parallel to power lines, “and don’t throw antenna wire over power lines–it’s dangerous.”

Eighty years ago, this couple were pulling in so many foreign stations on their two-tube receiver that they had to get out the globe to figure out where they were all coming from. They built the inexpensive set themselves by following the plans in the January 1941 issue of Popular Mechanics. Thanks to plug-in coils, the set could cover the broadcast band up to 9-1/2 meters. The set ran off household current, and could power either a loudspeaker or headphones. A 6SJ7-GT served as regenerative detector, with a 32L7-GT serving as audio amplifier and rectifier.

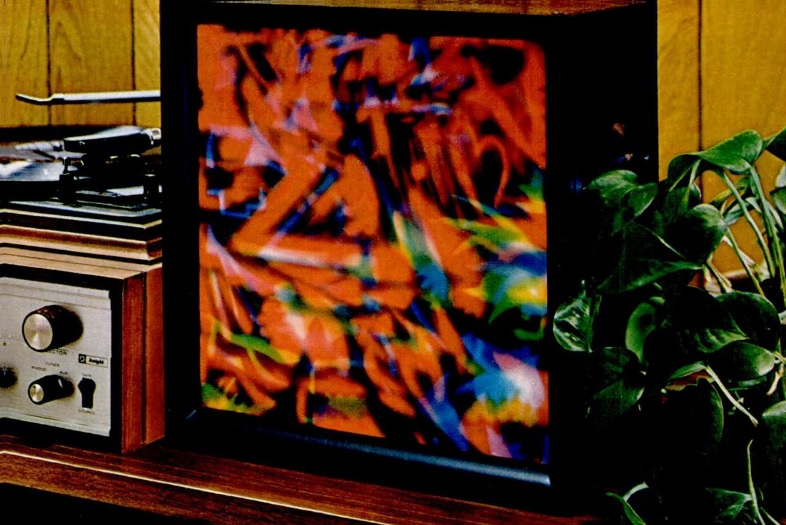

Fifty years ago, the December 1970 issue of Popular Mechanics showed how to make this “dancing light display”. The idea was quite simple, and employed no electronics. It simply used a string of Christmas tree lights made up of flasher bulbs mounted on the rear. These were projected through a cardboard with cutouts of various geometric shapes, only a sheet of plastic on the front. Optionally, a speaker could be mounted inside the cabinet.

Fifty years ago, the December 1970 issue of Popular Mechanics showed how to make this “dancing light display”. The idea was quite simple, and employed no electronics. It simply used a string of Christmas tree lights made up of flasher bulbs mounted on the rear. These were projected through a cardboard with cutouts of various geometric shapes, only a sheet of plastic on the front. Optionally, a speaker could be mounted inside the cabinet.

Even though the changing of the lights was random, according to the article, when music was playing, it would give the illusion of being in time with the music.

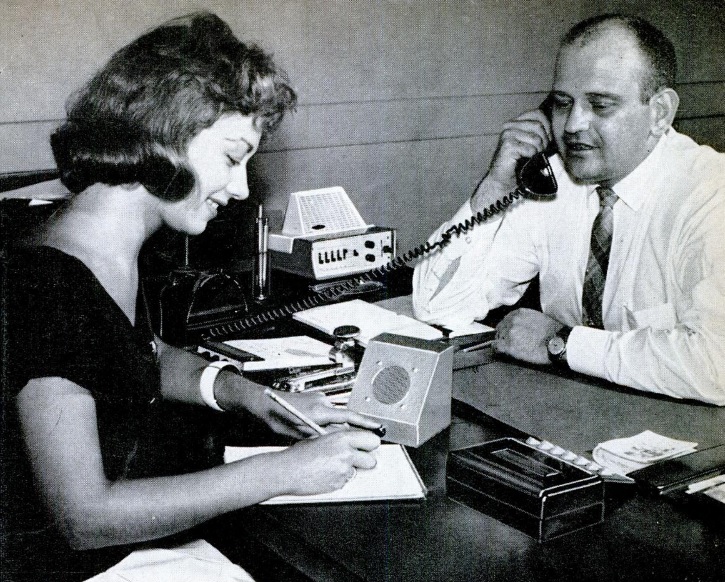

Sixty years ago this month, this stenographer dutifully takes down a verbatim transcript of her boss’s telephone conversation, thanks to a Lafayette telephone amplifier. The amp is connected to the phone through a telephone pickup coil, still readily available today. With it plugged into the amp, she can easily hear both sides of the conversation.

Sixty years ago this month, this stenographer dutifully takes down a verbatim transcript of her boss’s telephone conversation, thanks to a Lafayette telephone amplifier. The amp is connected to the phone through a telephone pickup coil, still readily available today. With it plugged into the amp, she can easily hear both sides of the conversation.

The unit was actually a kit. While it is not specified, we suspect that the secretary put it together herself, since it freed her of the need to use a headphone for such tasks, and probably made her work much easier.

The photo appeared in the December 1960 issue of Popular Mechanics, which highlighted a number of available kits, and pointed out how many, such as this one, could make things run more smoothly at the office.

EIghty years ago today, the December 27, 1940, issue of the Washington Evening Star carried this Sears-Roebuck ad for a radio-phonograph-recorder. The set came complete with microphone and five blank discs for $47.88.

EIghty years ago today, the December 27, 1940, issue of the Washington Evening Star carried this Sears-Roebuck ad for a radio-phonograph-recorder. The set came complete with microphone and five blank discs for $47.88.

It appears to be the Sears Silvertone model 5731. You can view some photos at this link.