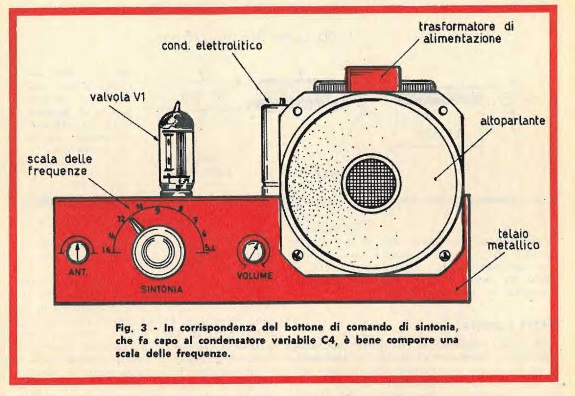

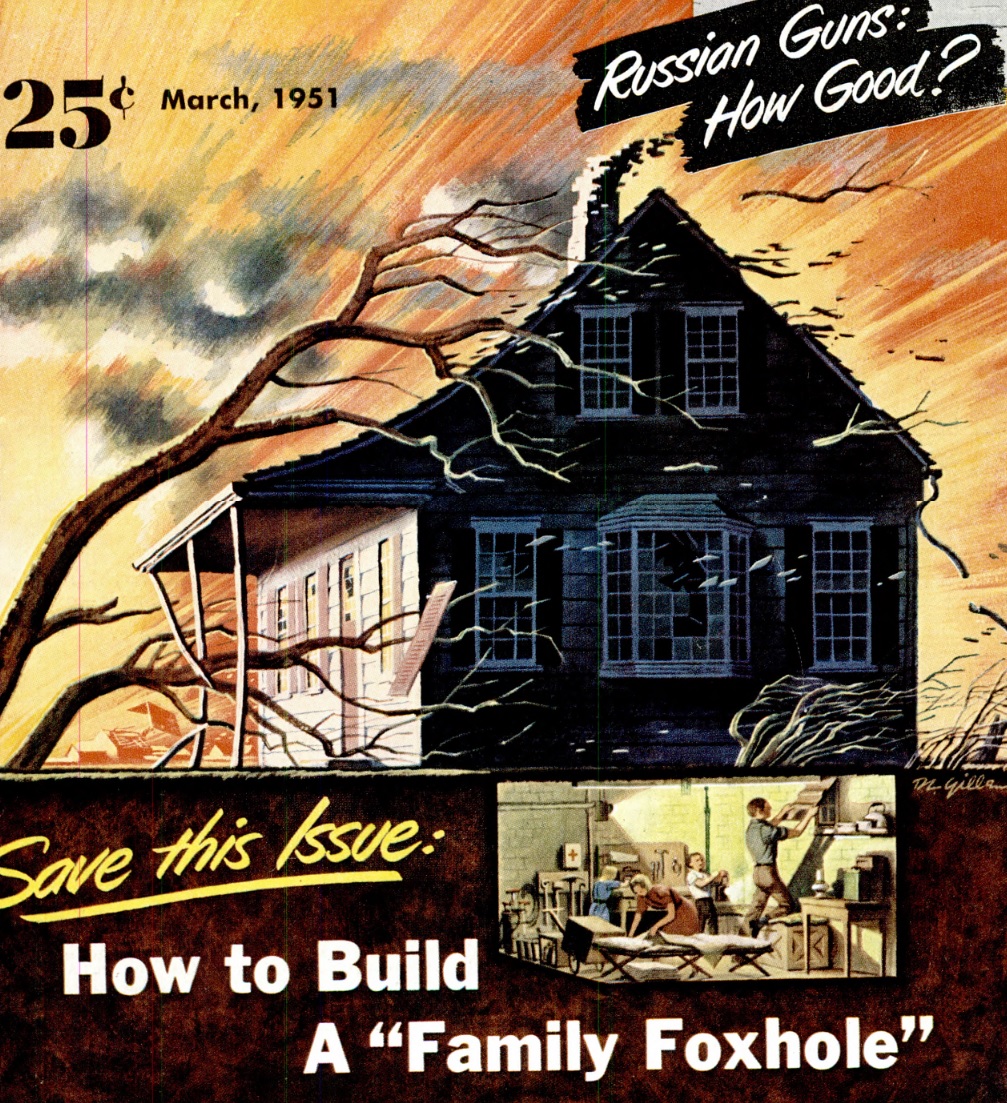

Seventy years ago this month, the cover of the March 1951 issue of Popular Science featured this artwork by artist Denver Gillen (who made the first drawings of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer, and later, numerous covers for Outdoor Life) showing “what an A-Bomb blast may do to your home,” but with an inset of a family safely hunkered down in their family foxhole.

Seventy years ago this month, the cover of the March 1951 issue of Popular Science featured this artwork by artist Denver Gillen (who made the first drawings of Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer, and later, numerous covers for Outdoor Life) showing “what an A-Bomb blast may do to your home,” but with an inset of a family safely hunkered down in their family foxhole.

The cover entreats the buyer to save the issue, since it contains a special section on emergency preparedness written by Michael Amrine, formerly of the Atomic Energy Commission.

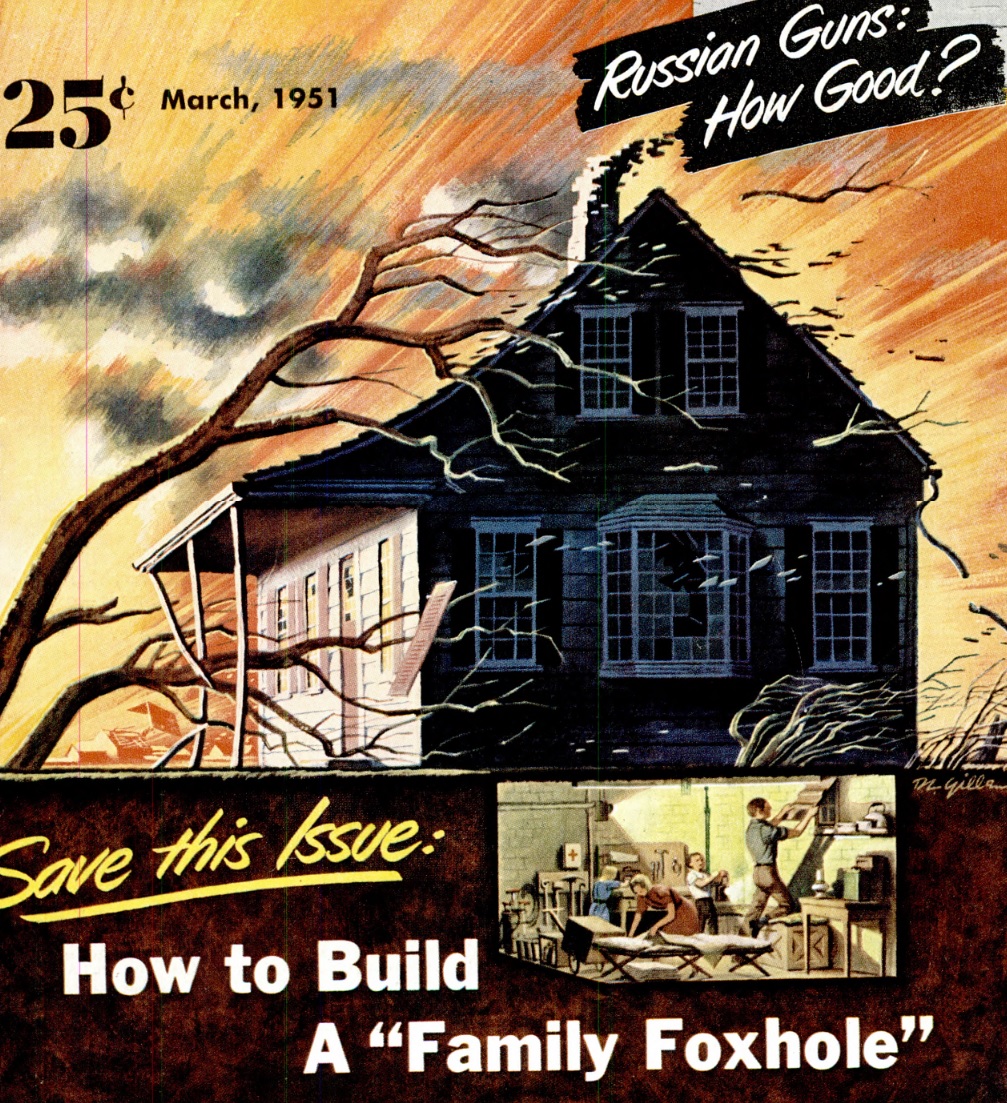

The magazine’s editors noted that much of the literature regarding civil defense was “tragic nonsense–aspirin for cancer. Even the official booklets say mainly, ‘Keep calm, keep covered, and follow directions.” But it goes on to say that official directions might not be forthcoming, since there did not exist civil defense organizations comparable with the problem. Instead, the magazine advocated “planning and plain hard work” by individual homeowners, and the magazine contained advice on how to do that. “The hard truth is that the most you can expect from civil defense will be control and rescue work after a bombing. The most effective preparation for atomic attack will be family by family, house by house.”

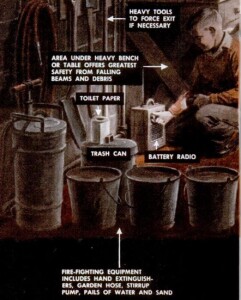

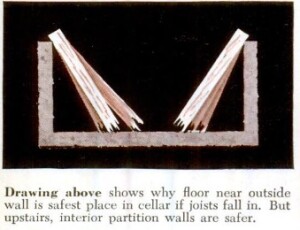

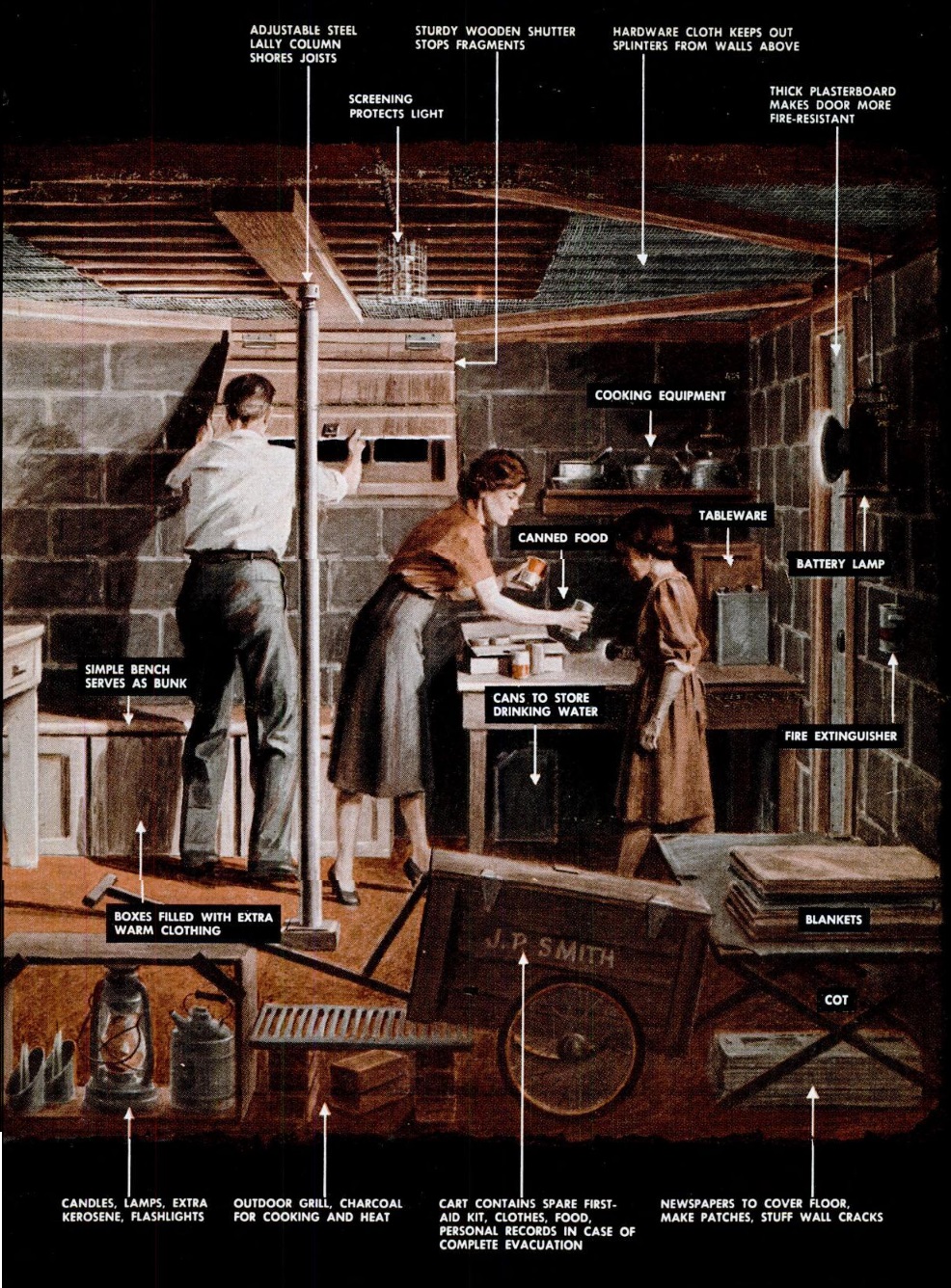

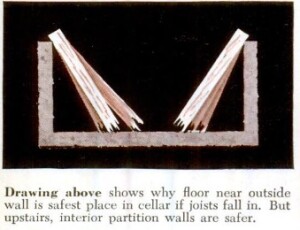

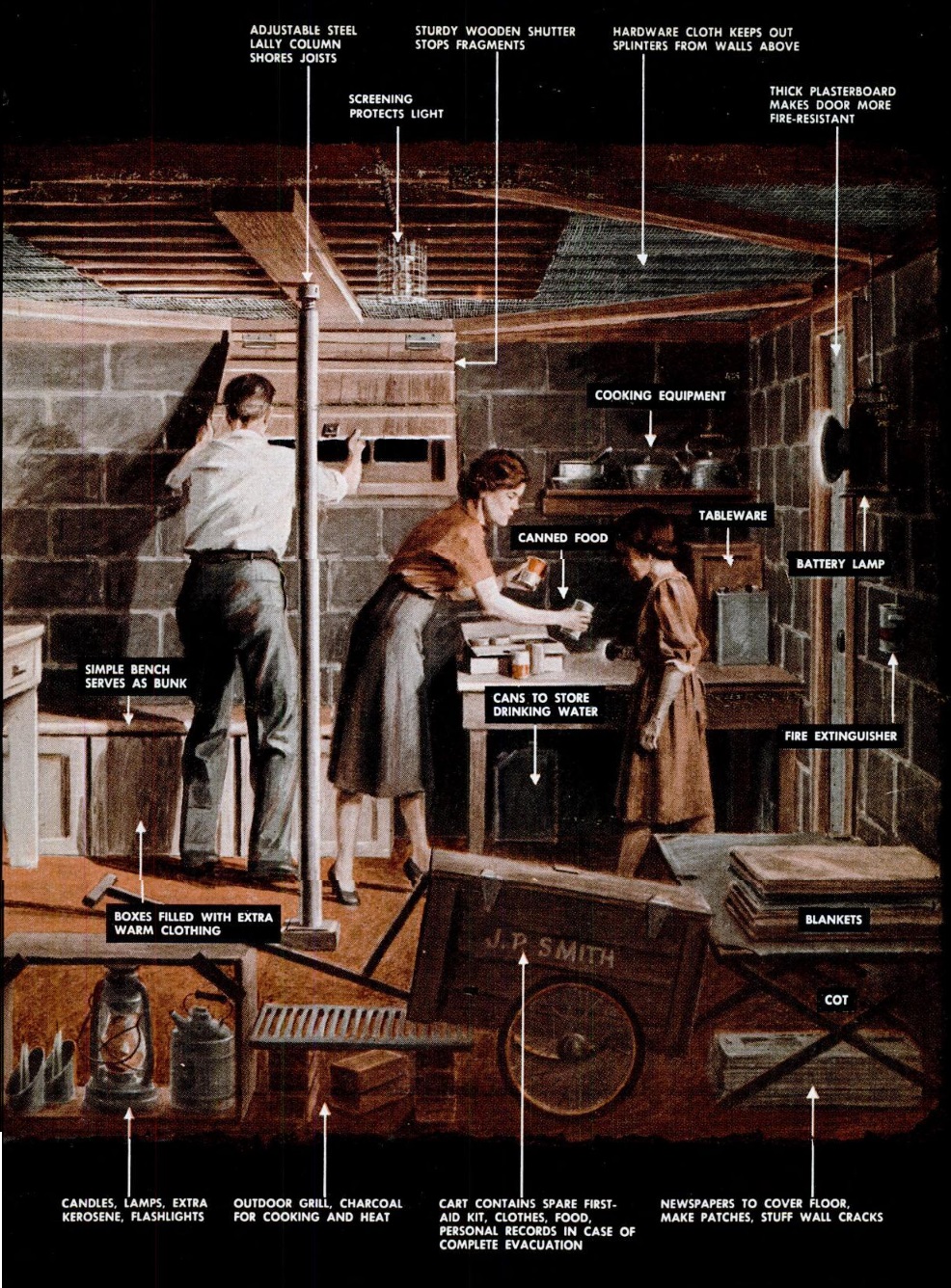

The article first noted what not to do, and pointed out that steps such as blacking out the house, taping windows, or even buying a Geiger counter were of very minimal utility. It noted that, as in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, radiation was not going to be the big killer. Instead, it would be the familiar forces of heat and blast, and the article gave pointers on preparing a refuge room to protect against them. The author asked readers to “imagine that your house is in a cyclone or hurricane belt, and next door to a gas tank” and plan accordingly. The most important principles in planning a refuge room were making sure there were at least two exits, keeping out from under heavy furniture or appliances, and preferably being in a corner of the cellar with the least windows or exposure. The importance of using a corner is illustrated by the drawing at left.

The article first noted what not to do, and pointed out that steps such as blacking out the house, taping windows, or even buying a Geiger counter were of very minimal utility. It noted that, as in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, radiation was not going to be the big killer. Instead, it would be the familiar forces of heat and blast, and the article gave pointers on preparing a refuge room to protect against them. The author asked readers to “imagine that your house is in a cyclone or hurricane belt, and next door to a gas tank” and plan accordingly. The most important principles in planning a refuge room were making sure there were at least two exits, keeping out from under heavy furniture or appliances, and preferably being in a corner of the cellar with the least windows or exposure. The importance of using a corner is illustrated by the drawing at left.

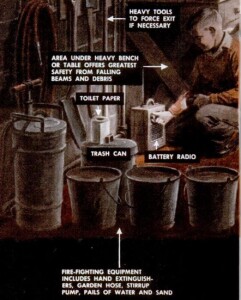

After a spot was located, ideas such as shuttering windows and making use of a heavy table or workbench were outlined.

The article included a number of frequently asked questions, including “what should I tell the children?” The answer was simple: the truth. They should be instructed where to go in a raid and how to hit the deck. You shouldn’t scare them, but don’t make it a game, either.

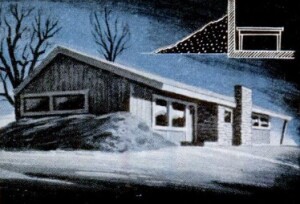

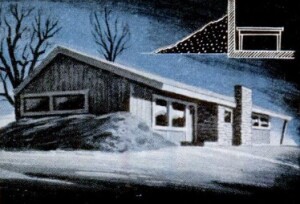

For homes without a basement, the author suggested placing earth or logs against an outside wall, with a sturdy table inside.

For homes without a basement, the author suggested placing earth or logs against an outside wall, with a sturdy table inside.

The list of recommended supplies included the usual suspects such as canned food and battery operated lights. Under the category of “valuables,” the recommendation included an extra pair of glasses and a lockbox for valuable papers. Rounding out that category was money (in small bills), on the assumption that, as in the last war, the economy would be in full operation.

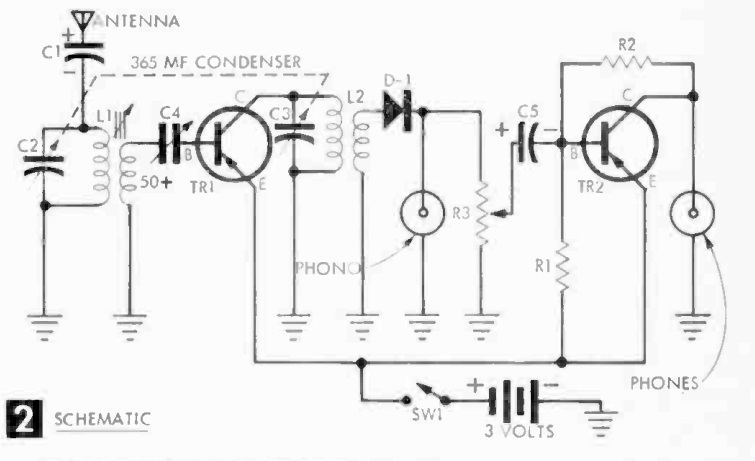

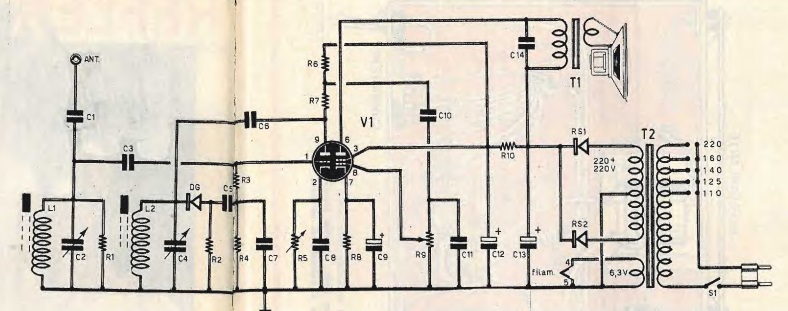

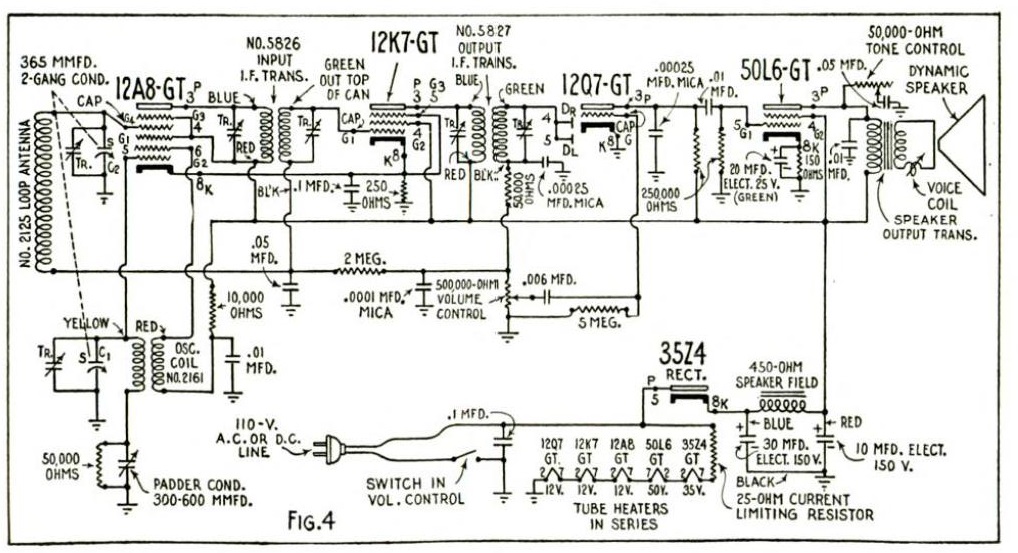

The list included a wind-up clock and maps of the city and county. The battery operated radio made its usual appearance on the list. The article noted that utilities would probably be out, although some, especially the gas lines, might continue to function for a time. Since battery operated radios were still quite rare (but not unheard of) in 1951, the article noted that a car radio would also work.

The article did note that it was dealing with just the Hiroshima-style A-bomb, and not the H-bomb. It notes that the H-bomb was then still just a theoretical possibility, but that if perfected, it would wreak the same level of damage over a still larger area.

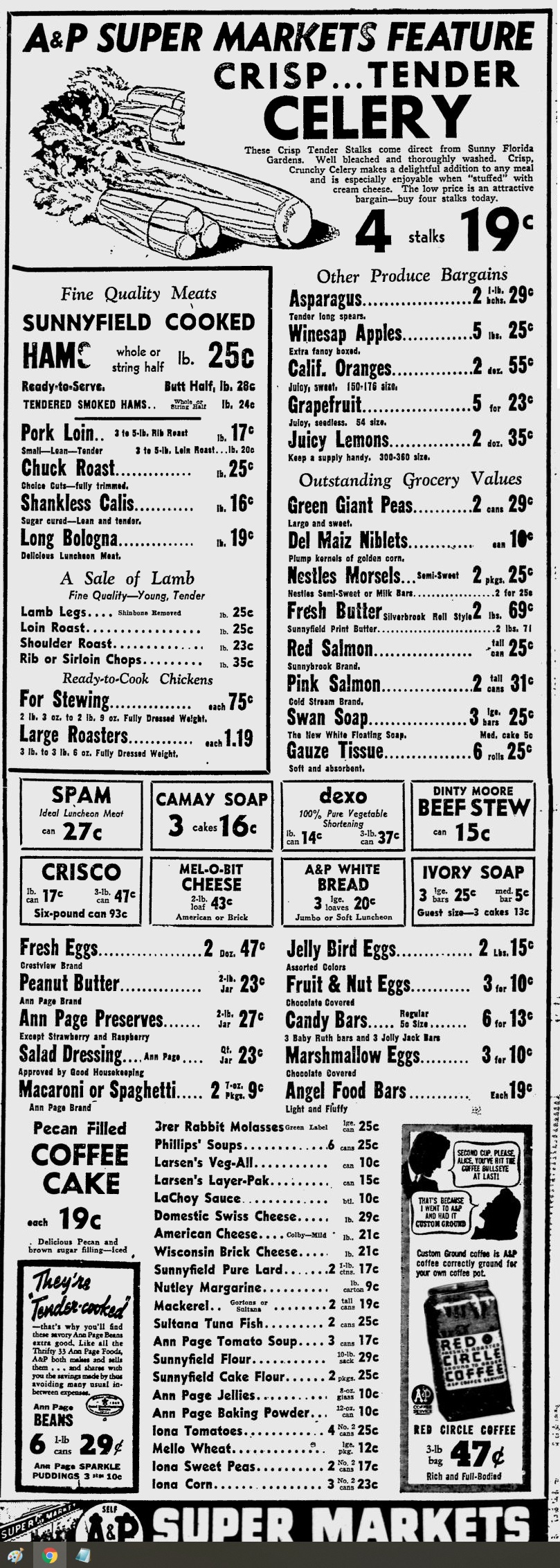

Here’s a snapshot of the cost of groceries just before World War II, from the Pittsburgh Press, March 28, 1941.

Here’s a snapshot of the cost of groceries just before World War II, from the Pittsburgh Press, March 28, 1941.