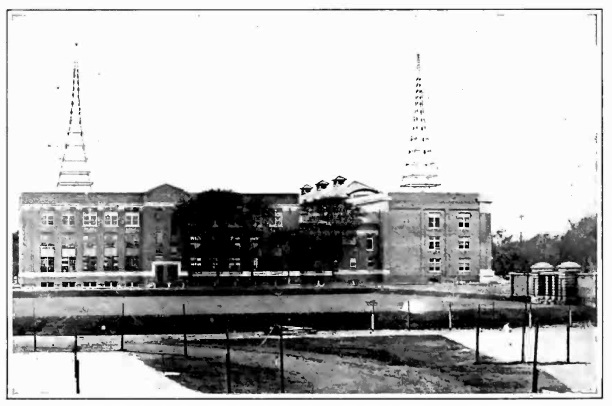

Today marks the 50th anniversary of WWV’s move to its current location in Fort Collins, Colorado. At 0000 hours GMT on December 1, 1966 (5:00 Mountain Standard Time on November 30), the station began its transmissions from the new location on the familiar internationally allocated standard carrier frequencies of 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 megacycles.

The move was announced in the November 1966 issue of Electronics Illustrated, which contained the photograph shown above. At the center of the photo is the station’s 10 MHz dipole antenna. The 3-1/8 inch diameter transmission line can be seen snaking off to the right. In the background to the left is the WWVB transmitter building (WWVB and WWVL had previously been located at Ft. Collins). The antennas in the background are, at the left, a backup 88 foot monopole, and at the right, the 400 foot WWVL tower.

To celebrate the move, the station issued a special first-day QSL card for reception reports on the first day. To ensure that SWL’s had really picked up the station, the voice identifcation used a special message on the first day, which had to be copied exactly to receive the special QSL, which is shown here.

According to the accompanying note on the card, WWV had apparently planned to award a photograph of the new station to the first three reception reports. However, it proved impossible to determine which were the first three, and three were selected from the batch. One of those went to long time ARRL staffer Lewis “Mac” McCoy, W1ICP.

The station had previously been located at Greenbelt, Maryland. The move was designed to give better coverage and to move the station closer to the National Bureau of Standards’ frequency standard lab in Boulder, Colorado.