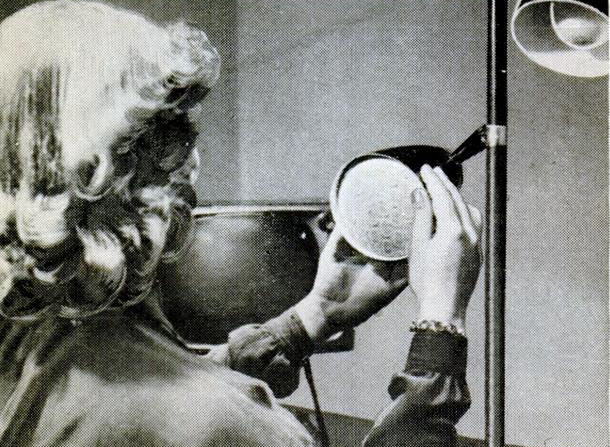

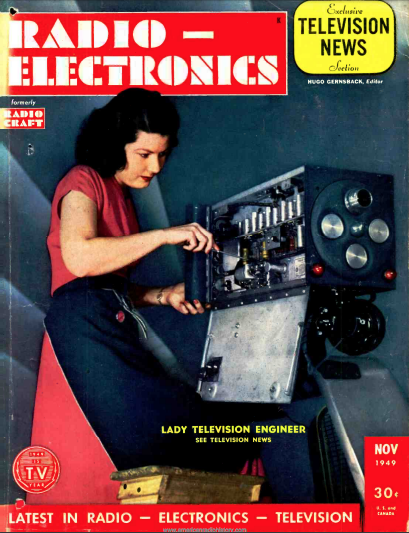

Shown here 70 years ago this month on the cover of Radio-Electronics, November 1949, is Rose Ann “Tex” Barbarite (nee Longnecker), described by the magazine as a “lady television engineer.” The magazine contains a brief autobiography of her as a pioneer in engineering.

Shown here 70 years ago this month on the cover of Radio-Electronics, November 1949, is Rose Ann “Tex” Barbarite (nee Longnecker), described by the magazine as a “lady television engineer.” The magazine contains a brief autobiography of her as a pioneer in engineering.

She writes that radio had been her hobby since her youngest days, when she built crystal sets with her brothers. When those were outgrown, they moved to vacuum tube circuits.

When she started a private girls school, however, she found herself unhappy, since the school viewed science and math as unnecessary for a girl. Undaunted, however, after graduation, she started at the Texas College of Mines in El Paso majoring in math. She was offered an electrical engineering scholarship at Purdue, where she found that the engineering profession was opening up to women, due to wartime labor shortages.

At the time of the magazine article, she was employed by RCA at its Exhibition Hall in New York. She had also taught basic radio theory and code to Civil Air Patrol cadets.

Ms. Barbarite eventually stopped working to raise four children. However, from 1985 to 1987, she was a member of the Peace Corps and taught at a high school in Belize. She died in 1998 at the age of 73 in Columbia, Maryland.

She was licensed as a ham in 1957 as W3FUS.