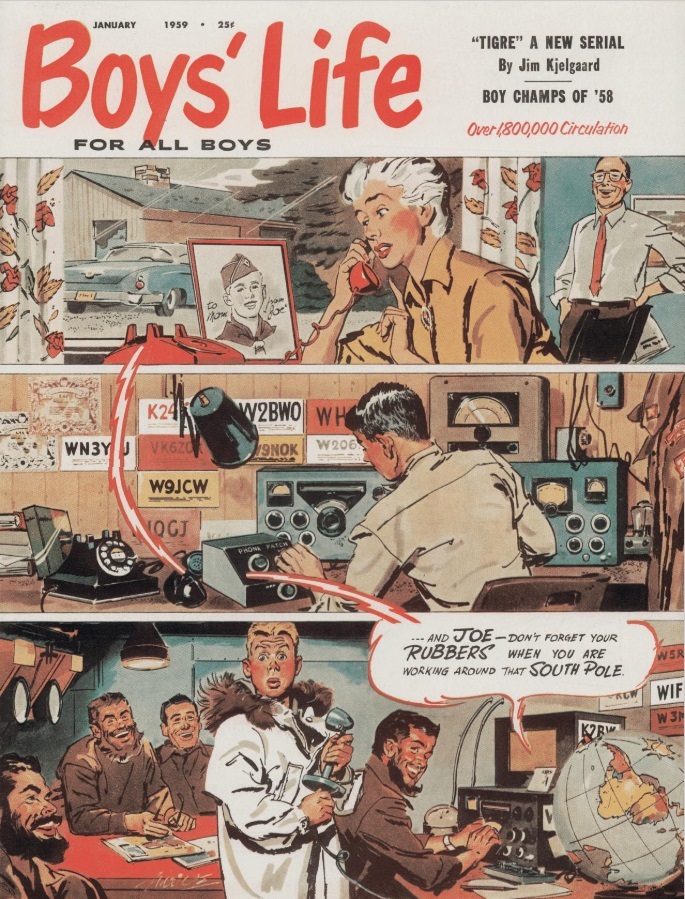

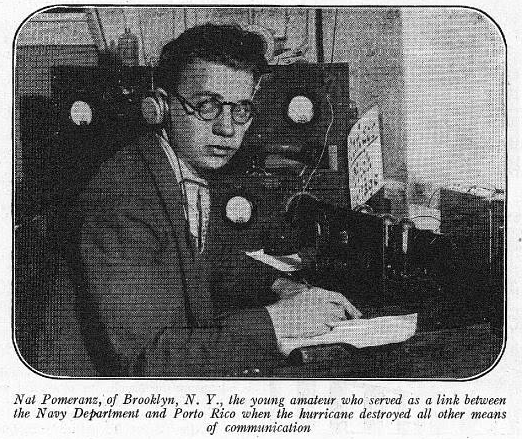

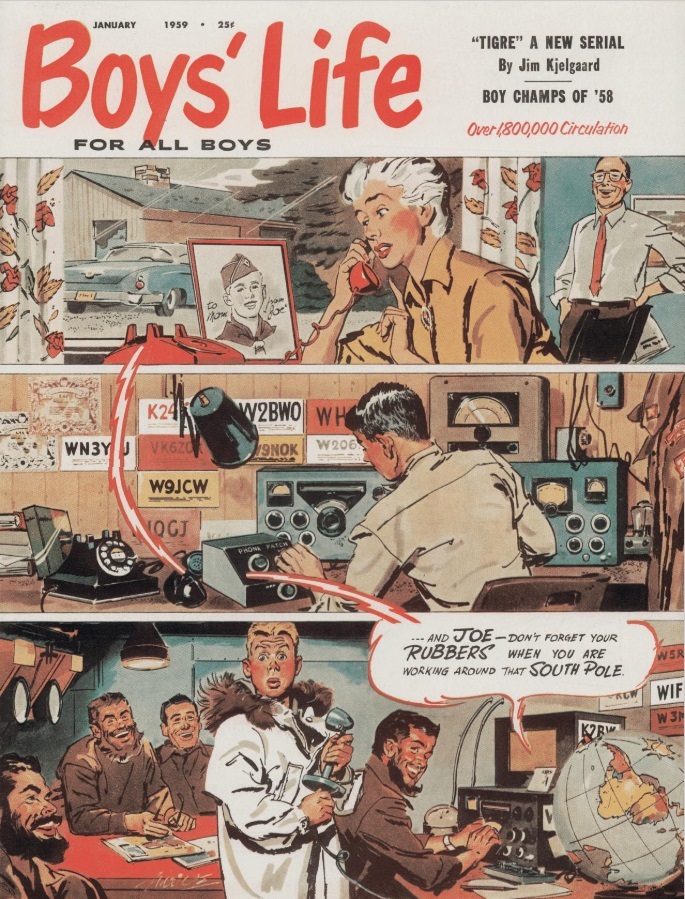

Sixty years ago this month, amateur radio made the cover of Boys’ Life magazine’s January 1959 issue, which featured an article entitled “Hamming is Fun” by long time ARRL staffer Perry Williams, W1UED.

The article featured the radio adventures of a number of young hams, including Jules Madey, K2KGJ, of Clark, NJ, who apparently inspired the cover. Madey, a high school student, put in as many as 49 hours a week running phone patches for men at the McMurdo base in Antarctica. Since the best conditions were in the middle of the night, Madey made a habit of going to bed right after supper and setting the alarm for 10:30 PM.

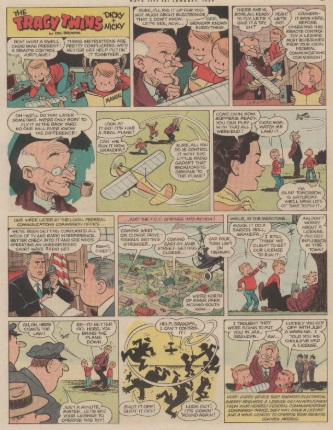

The magazine contains two more radio features. First of all, the Tracy Twins comic shows the boys receiving a radio control airplane that Grandpa insists on operating without a license. Of course, he gets busted as an FCC helicopter and car swoop in. Fortunately, he gets off with a warning.

The magazine contains two more radio features. First of all, the Tracy Twins comic shows the boys receiving a radio control airplane that Grandpa insists on operating without a license. Of course, he gets busted as an FCC helicopter and car swoop in. Fortunately, he gets off with a warning.

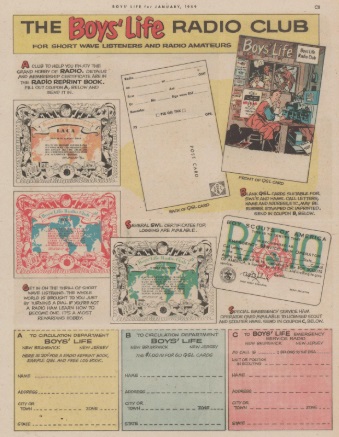

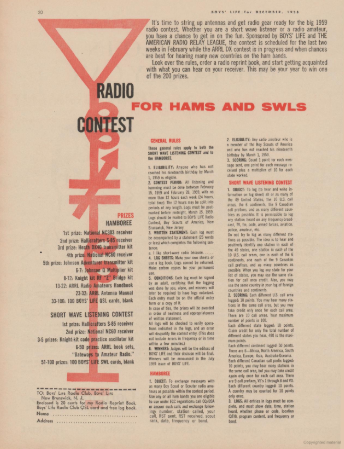

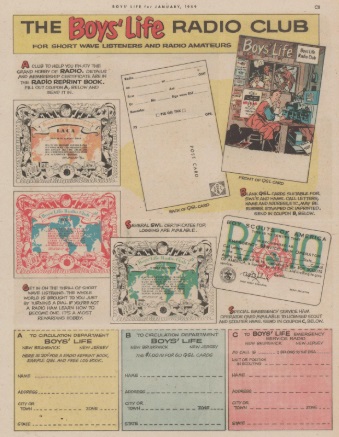

Finally, the Boys’ Life Radio Club had three offerings. For just 20 cents, they would send out the Radio reprint book containing reprints of earlier articles, along with a free log book. One dollar would get 60 QSL cards. And for no cost, the club would send any licensed ham operator scout or scouter a card identifying the bearer as an emergency service ham.

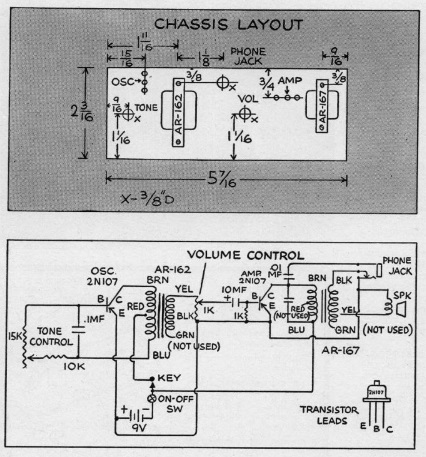

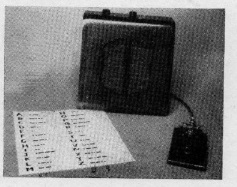

Sixty years ago this month, the March 1959 issue of Boys’ Life showed scouts how to put together this two-transistor code practice oscillator. Powered by six penlight cells, one 2N107 transistor served as oscillator, with the other as an audio amplifier. So chances are, the output was both clean and loud. The set featured both tone and volume controls, and had provision for headphones or a built-in speaker.

Sixty years ago this month, the March 1959 issue of Boys’ Life showed scouts how to put together this two-transistor code practice oscillator. Powered by six penlight cells, one 2N107 transistor served as oscillator, with the other as an audio amplifier. So chances are, the output was both clean and loud. The set featured both tone and volume controls, and had provision for headphones or a built-in speaker.