I remember seeing this notice (or possibly one like it from another source) fifty years ago in the March 1973 issue of Boys’ Life magazine.

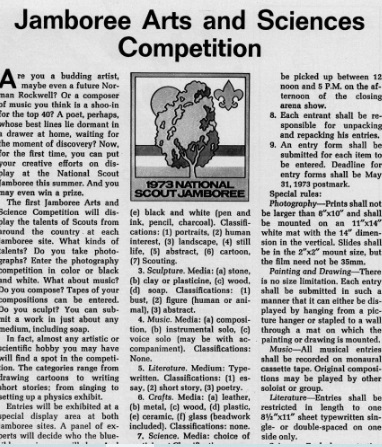

I remember seeing this notice (or possibly one like it from another source) fifty years ago in the March 1973 issue of Boys’ Life magazine.

As an aspiring scientist and Tenderfoot Scout, I was, of course interested in this opportunity to showcase my scientific knowledge before a national audience. The quadrennial National Scout Jamboree was to take place that year, and I was going. Normally, mere 12-year-old Tenderfoots did not participate in this event, but 1973 was an exception. That year, the Jamboree was being held at two separate locations, in Pennsylvania and Idaho. 1973 was the only year it was split that way. And 1973 also had the distinction of being open to regular troops. Normally, individual scouts sign up and are assigned to a provisional Jamboree troop. But in 1973 the BSA made the good decision, never repeated unfortunately, to open it up to all scouts to attend along with their normal troop and leaders. (Among the other events was the “wide game”, about which I’ve previously written.)

By March of that year, we were already signed up, and this announcement showed another opportunity. The Jamboree was to host an “Arts and Sciences” competition–a science fair combined with an art exposition. I don’t even remember the art part of the event, but I did sign up right away for the science fair. My exhibit was Atomic Energy, and I cobbled together a few interesting objects to put on display on my assigned 2-1/2 by 4 foot table. I remember borrowing a Geiger counter from the county civil defense department, and I had an illustrated brochure from the Monticello nuclear power plant. It was set up in a tent somewhere on the Jamboree grounds. After setting it up, I did visit a couple of times, although there wasn’t a lot of traffic.

I didn’t come home with a blue ribbon, but I did earn a red ribbon. In retrospect, it was probably a participation trophy, but it’s still a prized possession. Interestingly, this was before I got my ham license, and I never did run into KJ7BSA, the Jamboree’s special event station.