T.E. Nikirk in 1923.

(QST, Feb. 1923, p. 29.)

When I look for historical items for this blog, I usually start by browsing old magazines or newspapers looking for items of interest. In most cases, they’re interesting in their own right as showing what life was like in the early part of the twentieth century, especially with respect to the new field of wireless. I usually make some effort to follow up on the people involved, but the trail usually grows cold, and I’m often left wondering what happened to the people who had one newsworthy accomplishment.

Such was not the case, however, for one Thomas Edison Nikirk of Washington, D.C. Mr. Nikirk, born in 1901, was a thirteen-year-old Boy Scout in Troop 10 when he made the pages of the Washington Times on several occasions in 1914. The May 31 issue reported that young Mr. Nikirk had earned Personal Health merit badge. The October 11 issue reported his earning the Cooking merit badge.

The Wireless Merit Badge wasn’t created until 1918, so it’s unlikely that Thomas ever earned it. But had it been available, it’s likely that he would have been one of the first, as evidenced by this article in the paper’s June 7 edition:

Thomas Edison Nikirk a Wireless Operator

Scout Thomas Edison Nikirk, of Troop 10, is now registered as a wireless operator with permission to operate anywhere in the United States. He obtained his papers the first part of last week and has the distinction of being the only Boy Scout wireless operator in the District. Tom is in his fourtenth year, and has been for the past seven months a student of H.B. DeGroot, who teaches a wireless class in this city.

According to the 1916 Call Book, Nikirk held two call signs. His main call, licensed at 411 12th St. SE, Washington, D.C., was 3VU. He also held the call 3EE, which the book indicates was for a portable station. (According to the same book, his “Elmer,” H.B. DeGroot, was the licensee of special land station 3ZH. It’s likely that DeGroot was affiliated with the Scout troop, since one Alfred DeGroot earned the rank of Eagle Scout on October 30, 1920, according to the National Eagle Scout Association database.)

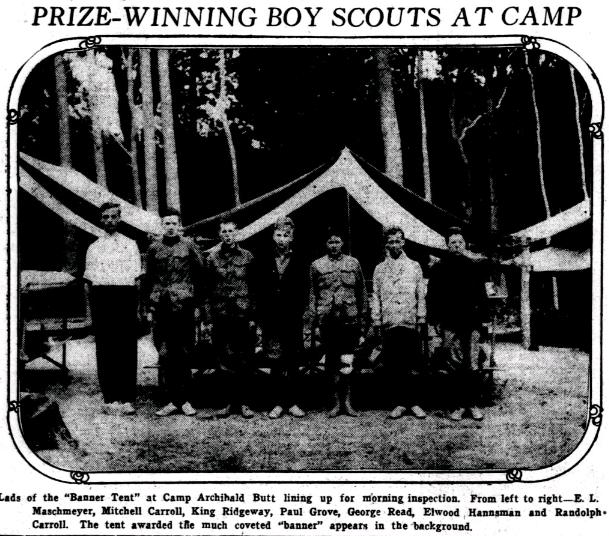

According to the July 26 issue of the Times, young Mr. Nikirk, the ink barely dry on his new license, brought his wireless station to summer camp. The paper reports that a number of national and council officials visited Camp Archibald Butt at Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. A number of them stayed overnight, and were able to see a demonstration of 3VU’s capabilities. The paper reports that Nikirk was “experimenting with his wireless outfit, receiving and sending messages at long distances. Recently he attempted to receive a wireless message from Washington, but did not succeed with the twenty-foot aerial now in use at the camp.”

(The Camp was operated from 1914-16 by the Washington and Baltimore Councils of the BSA, and was named after Maj. Archibald Butt, an aide to Presidents Taft and Roosevelt, who died in the sinking of the Titanic. I’m not sure of his connection with Scouting, but Butt is shown in this 1912 photo along with Lord Baden-Powell and President Taft.)

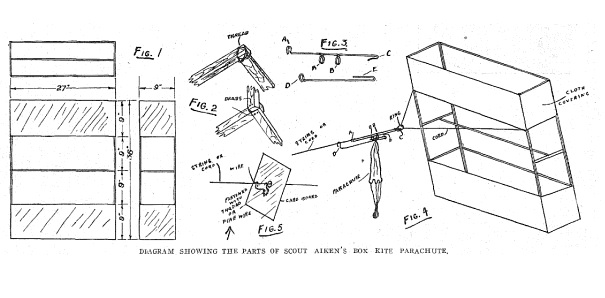

Undoubtedly disappointed by the poor July performance of the aerial, Thomas promptly set out to improve on it. The paper’s August 9 issue carries the following dispatch from camp:

CAMP BUTT RADIO TOWER IMPROVED

Thirty-Foot Aerial Expected to Send Messages for 100-Mile Radius.

Following many futile attempts with the thirty-foot wireless tower at Camp Archibald Butt, Cheseapeake Beach, Md., to transmit messages at long distances, a new aerial, twice the height of the one found wanting, has been devised and is now in operation with Scout Thomas Nikirk, of Troop No. 10, acting as wireless operator. Nikirk asserts that with the aid of the newly constructed aerial, he will, under normal conditions of the weather, be able to send and receive messages within a radius of 100 miles.

At some point between 1916 and 1920, Thomas moved to California. The 1920 edition of the amateur call book shows him licensed for 500 watts as 6KA, and the general call book shows him as the licensee of experimental station 6XBC, both at 1050 West 89th St., Los Angeles, Calif.

In many cases when I research an old name, the trail will grow cold at this point. But Thomas Nikirk went on to be a prominent California Ham operator, and continued to hold the call 6KA (later to become W6KA) until his death in 1955.

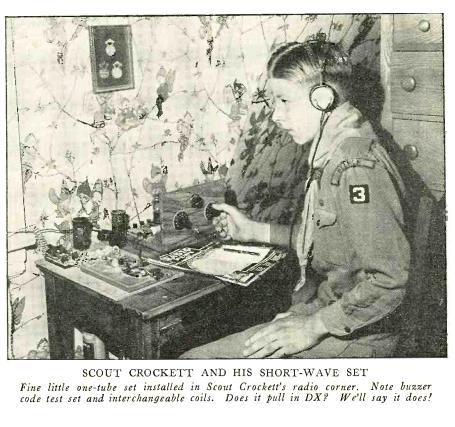

By 1923, Nikirk had by all accounts one of the best amateur stations on the West Coast. He is featured in two articles in the February, 1923, issue of QST. The first article (from which the photo above is taken) reports that his signals had bridged the Pacific, and had been heard off the coast of China, at a point reported as being 5830 miles west of San Francisco. And in addition, his signals had been copied in Europe. After listing the stations heard off the coast of China, QST opines:

With all due credit to the entire list of successful stations, we think that 6ZZ [in Douglas, Arizona] and 6KA are the stars, for they are in the China list and they also got over to Europe, including all the long 2500-mile drag over the Rockies and across the United States. That is real performance and represents so much more of an accomplishment than the Atlantic crossing by eastern stations.

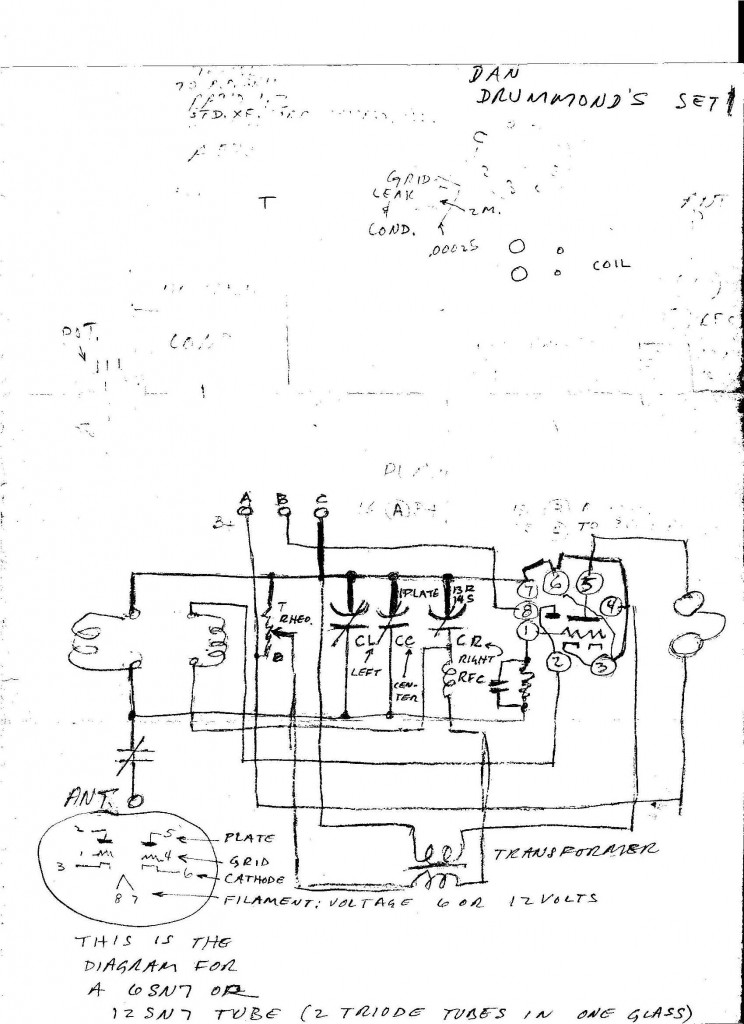

It goes on to describe “6KA, the ether-buster of T.E. Nikirk at Los Angeles,” whose antenna was a “T”, with five wires on 14 foot spreaders, running 57 feet long and 73 feet high, and with a 9-wire counterpoise covering an area measuring 45 by 70 feet.

The transmitter consisted of a single tube rated at about 250 watts. The normal antenna current was 12-13 amps. It reports that the plate current could be run up to 8000 volts! Normally, however, he ran closer to 3000 volts.

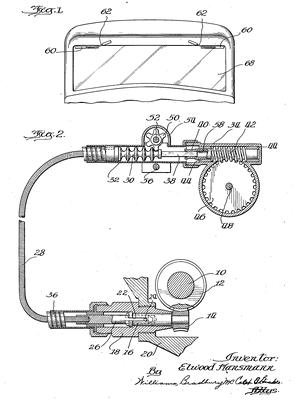

How he managed to get that much DC voltage on the plate is described in another article in the same issue, authored by Nikirk, entitled, “Synchronous Rectifiers for Plate Supply: A 3600 R.P.M. Rectifier.” In that article, he describes a mechanical rectifier consisting of a synchronous motor running at 3600 RPM, spinning a bakelite disc with two semicircular conductive edges. The high voltage AC from the transformer was fed to two brushes on opposite sides of the spinning disc. Two other brushes served as the output. The net effect was that the polarity reversed twice each cycle. Therefore, the output consisted of direct current.

According to a 1939 issue of Radio News, Nikirk served as chairman of the Federation of Radio Clubs. He is also the author of a Stray in the December 1946 issue of QST regarding the use of floor wax to repel water on transmission line.

According to his front-page obituary in the San Marino (Calif.) Tribune, July 14, 1955, he died of a heart attack. The paper reported that in addition to his ham station, he was the owner of an electronics store in Pasadena. He was a member of the Institute of Radio Engineers, the Pasadena Amateur Radio Club the ARRL, and a newly formed medical electronics group at Cal Tech. During World War 2, he served in the Air Force.

The call sign W6KA is still assigned, and is now held by the Pasadena Radio Club, of which Nikirk was a member.

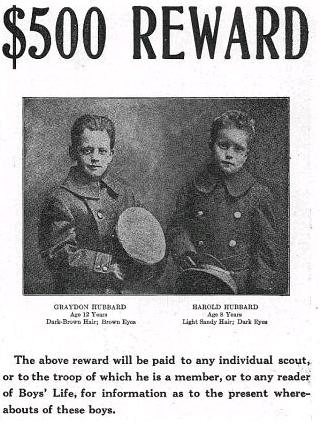

Finally, it appears that Thomas Nikirk’s Troop 10 was in existence until about 1940. According to the NESA database, nineteen Scouts from that troop earned the rank of Eagle between 1919 and 1940. As noted above, one of those Scouts was Alfred DeGroot, who became an Eagle Scout in 1920, and who I suspect was the son of 3ZH. Surprisingly, one of those Troop 10 Eagle Scouts was science fiction author and religion founder L. Ron Hubbard. According to the NESA database, his Eagle Board of Review date was March 28, 1924.

The Washington, D.C. Council, of which Troop 10 was a part, is now known as the National Capital Area Council of the BSA, and covers much of Maryland and Virginia, as well as the U.S. Virgin Islands. From the list of “Troop 10” Eagle Scouts, it appears that the troop number was reused multiple times, since there were Scouts from both Maryland and Virginia who became Eagles in the years 1959-1964, 1973-1977, 1989-1999, and 2001 through the present. The current caretaker of the Scouting legacy of Scout Thomas Edison Nikirk is Troop 10 of the Piedmont District of the National Capital Area Council, located in Warrenton, Virginia.

Seventy years ago today, November 19, 1944, these four young men were featured in the Chicago Tribune after having become Eagle Scouts. For the first time in the history of their community, five Scouts had become Eagle at the same time.

Seventy years ago today, November 19, 1944, these four young men were featured in the Chicago Tribune after having become Eagle Scouts. For the first time in the history of their community, five Scouts had become Eagle at the same time.