You are probably on this page because you, or your child, have a science fair project that’s due tomorrow, and you haven’t even started! We feel your pain! Listed below are some of our earlier science fair projects that can be done in a very short amount of time, and with materials that you probably already have around the house. (You won’t have time to make the Jacob’s Ladder shown above, but you still have a chance to take home the blue ribbon.)

You are probably on this page because you, or your child, have a science fair project that’s due tomorrow, and you haven’t even started! We feel your pain! Listed below are some of our earlier science fair projects that can be done in a very short amount of time, and with materials that you probably already have around the house. (You won’t have time to make the Jacob’s Ladder shown above, but you still have a chance to take home the blue ribbon.)

If you have more time, you might want to browse through our entire category of science fair projects. But most of those ideas require too much time, and/or require things that you don’t have.

The projects shown on this page can be done immediately, and your teacher won’t know that you waited until the last minute! Listed below are the projects, along with a list of materials.

Most of these projects are adaptable to various grade levels, so look them over and find what’s appropriate. Follow your teacher’s instructions, as the project will also include a display board, writing a question that the experiment answers, and other requirements. But with one of these projects, an acceptable experiment can be done in less than an hour with materials you already have.

- Lens Simulator made with sand

Materials needed: Sand, cardboard - Balancing Act

Materials needed: Ruler, hammer - Trajectory of a moving object

Materials needed: Two marbles, hacksaw blade or similar springy object - Viscosity

Materials needed: Two cans, string, water, sand or something similar (salt, sugar, etc.) - What melts faster: Clean snow or dirty snow?

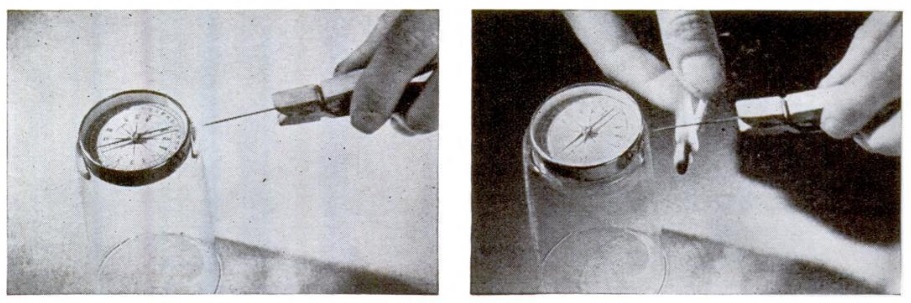

Materials needed: Lamp, snow, two glasses - Earth’s magnetic field

Materials needed: Cork, magnet, cup, water - Measuring the moon’s diameter

Materials needed: Cardboard, tape. (Can only be done on a night when the moon is visible.) - Homemade boxes

Materials needed: Paper - Sound through a string

Materials needed: Spoon, string - Vinegar and baking soda

Materials needed: Vinegar and baking soda; mothballs and/or candle - Parabolic reflector

Materials needed: Two umbrellas. - Airfoils

Materials needed: Candle, cardboard - Best clothing to keep you cool

Materials needed: Lamp, candle, black and white cardboard - Center of mass

Materials needed: Cardboard, nail, string - Time zone converter

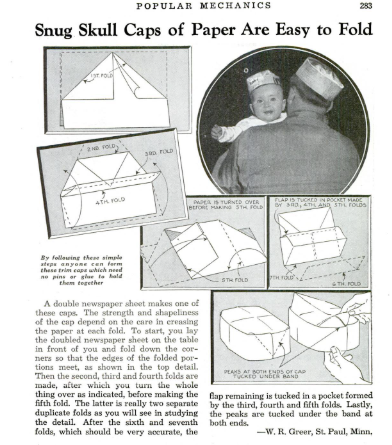

Materials needed: Paper and access to printer - Making a pressman’s cap

Materials needed: Large sheet of paper