This weekend was Winter Field Day, an event in which amateur radio operators set up at a remote location and see how many contacts they can make. Two years ago, many hams stayed home in the mistaken belief that being in a field somehow causes COVID. To dispel that notion, I set up at a state park campground, where I operated while socially distancing myself hundreds of feet from other persons.

This weekend was Winter Field Day, an event in which amateur radio operators set up at a remote location and see how many contacts they can make. Two years ago, many hams stayed home in the mistaken belief that being in a field somehow causes COVID. To dispel that notion, I set up at a state park campground, where I operated while socially distancing myself hundreds of feet from other persons.

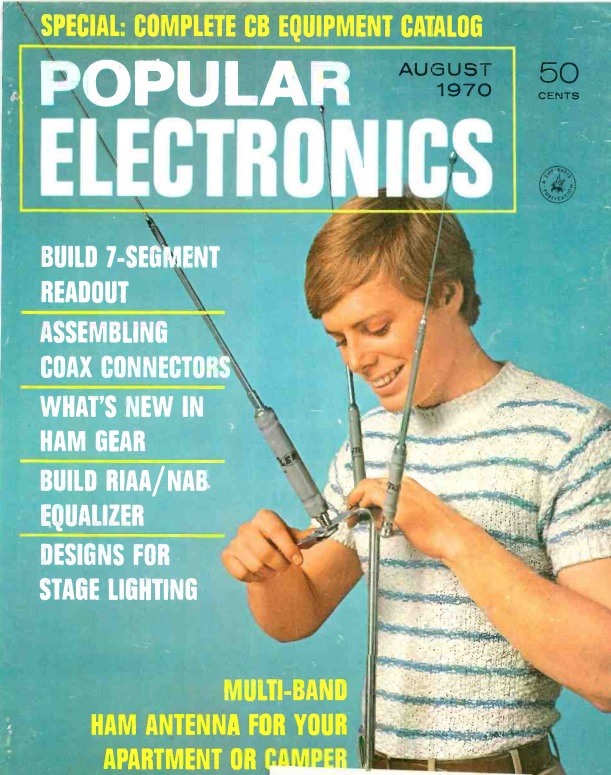

Last year, I operated a little bit from home, albeit with battery power, and doing my best to work only portable stations. But the name of the event is Field Day, and it doesn’t make a lot of sense to do it anywhere but out in the field. Santa Claus recently gave me a new QRP (low power) radio, the QCX Mini for 40 meters, and this was a good opportunity to put it to work.

Review of QCX Mini

I’ve had the QCX Mini, a product of QRP Labs, a few weeks now, and I’m absolutely amazed at how well this radio works. It weighs less than half a pound, and can easily be held in the palm of your hand. It’s available for multiple bands, but I chose 40 meters, which is almost always open to somewhere, day or night. Winter Field Day is, in addition to being a fun activity, an exercise in emergency preparedness, and this tiny rig is one that you could carry with you anywhere. You just need to plug it into a key, headphones, power supply, and antenna. It’s an excellent CW transceiver, and in many ways, it’s comparable with even the best stations.

The receiver is possibly a little less sensitive than a full-size receiver at home, but it’s more than adequate for QRP use. My best DX with it so far was Austria, I was able to pull in the other station’s signal, and he was able to hear me. Additional sensitivity wouldn’t really add much.

It is, however, extremely selective, and has a narrow filter which is ideal for CW. The downside is that the filter is an analog filter permanently wired in, so it’s really not possible to copy AM or SSB signals. You can hear them, and make them out to some extent, but not very well. For example, the receiver is able to tune to both 5 and 10 MHz, and I can hear the beeps from WWV, but can’t really copy the voice messages.

In addition to the transmitter and receiver, the little radio has a built-in keyer, and even a code reader. The code reader doesn’t work quite as well as the one between my ears, but it actually does come in handy. Occasionally, I might miss a letter, but there it is, right on the screen. And if I forget a call sign before writing it down, it’s there on the screen for a few seconds until it scrolls away.

I haven’t tried it out yet, but the QCX Mini also contains a WSPR beacon that might be fun to play with. You can read the QST review of the radio at this link.

If someone wants to get into amateur radio very cheaply, and they’re willing to learn Morse Code, the QCX Mini would be a very inexpensive way to start. Completely assembled, it sells for about $120. Of course, knowledge of Morse code is necessary, but the code reader makes the learning curve a bit easier. As long as the station you’re working is sending reasonably good code, the built-in reader will help you catch all or most of what you might have missed. Even if you’re a little unsure of your abilities at first, you can get on the air right away, and build your speed up on the air, rather than having to worry about “practicing.”

In kit form, the radio is only $55, although you probably want to spend an additional $20 for the case. (But it would work fine with the printed circuit boards exposed.) If you get the models for 80, 40, or 15 meters, only a technician class license is required, and that can be done with a weekend of study (perhaps using the study guide I authored).

Winter Field Day Summary

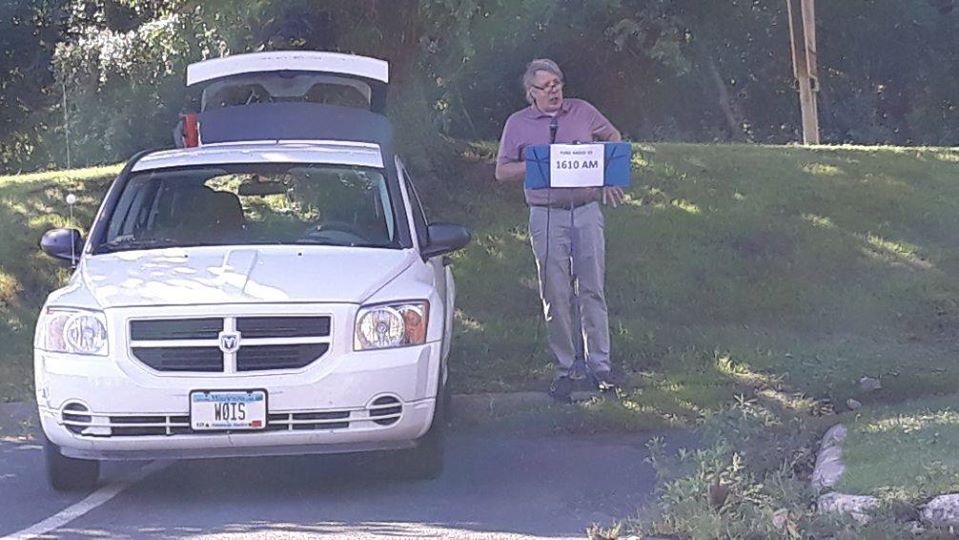

The contest incentivizes operating away from home, so I decided to trek a bit further than my own back yard. I toyed with the idea of just sitting in a folding chair outside, but the temperature was only 5 degrees Fahrenheit, so I opted to sit inside the car for a little protection from the elements. I found an almost-empty parking lot at Como Park in St. Paul, MN, and decided to operate for a couple of hours from there.

The contest incentivizes operating away from home, so I decided to trek a bit further than my own back yard. I toyed with the idea of just sitting in a folding chair outside, but the temperature was only 5 degrees Fahrenheit, so I opted to sit inside the car for a little protection from the elements. I found an almost-empty parking lot at Como Park in St. Paul, MN, and decided to operate for a couple of hours from there.

The 40 meter band is best during nighttime hours, but I wanted to avoid sitting in the dark as much as possible. So I arrived at about 4:00 PM local time, and stayed until a little after 6:00. Most of my time there was in daylight, but with very good band conditions.

My antenna was an inverted-vee dipole. The center was held up with my trusty golf ball retriever shoved into a snowbank next to the car, and the ends were tied to the ground. Normally, I just pick up a stick off the ground and use that as a stake, but when I got there, I realized that all of the sticks were buried under two feet of snow. A search of my car found a water bottle, which I pushed into the snow to serve as an anchor at one end, and my windshield scraper, to which I tied the other end. The antenna, made of cheap speaker wire, was up in about 10 minutes. Since I was in my car, I just plugged the radio into the lighter socket. But I would normally run it with my fish-finder battery. In fact, the radio will work just find on as little as a 9-volt battery, although I’m guessing one battery would last less than an hour or so. A better compromise for small size but reasonable battery life would be 8 AA batteries or 8 D cells.

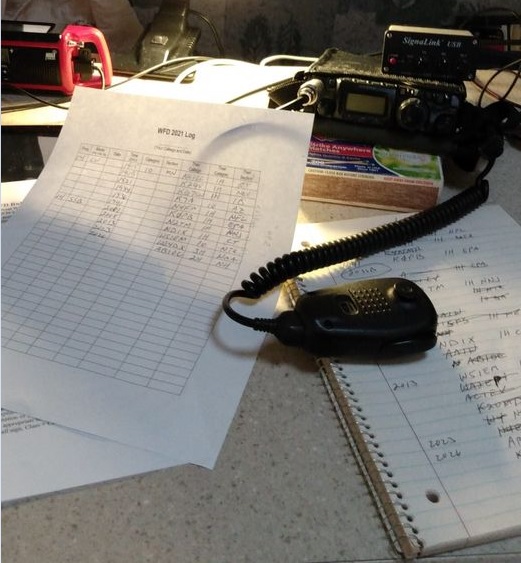

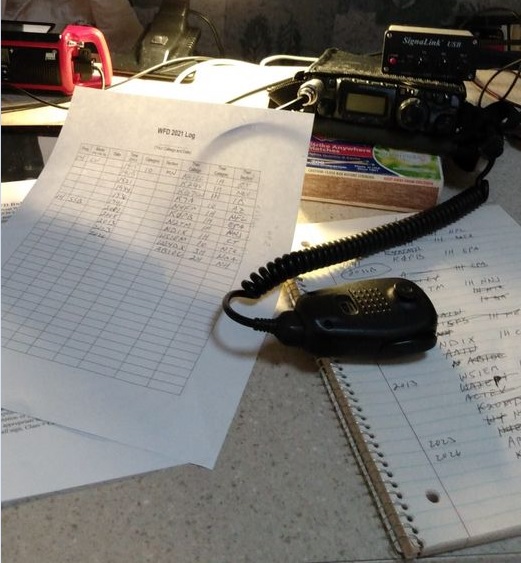

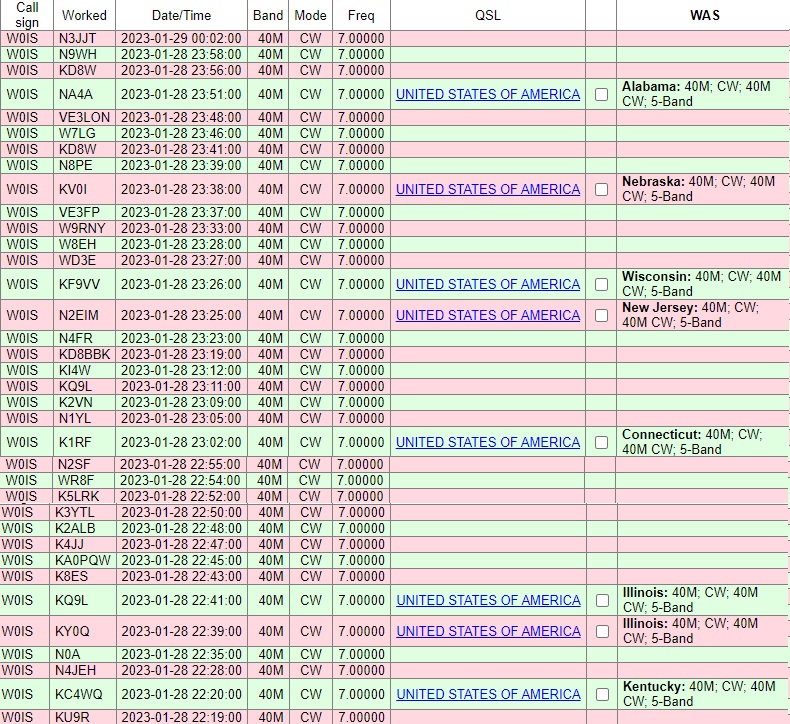

As soon as I turned on the radio, it sprang to life, and I made a total of 34 contacts over the course of two hours. You can see from my log below, the radio does get out. The log image below was made shortly after the contest and confirmations continue to trickle in, but other states worked included Texas, Louisiana, New York, and Pennsylvania, as well as Ontario, Canada. Surprisingly, I worked nothing to the west, but there are a couple of explanations. Forty meters is primarily a nighttime band, and it was still daylight to the west of me. Also, the antenna had an east-west orientation, meaning that it would get out the best to the north and south, which explains the good signal into Texas and Louisiana.

As soon as I turned on the radio, it sprang to life, and I made a total of 34 contacts over the course of two hours. You can see from my log below, the radio does get out. The log image below was made shortly after the contest and confirmations continue to trickle in, but other states worked included Texas, Louisiana, New York, and Pennsylvania, as well as Ontario, Canada. Surprisingly, I worked nothing to the west, but there are a couple of explanations. Forty meters is primarily a nighttime band, and it was still daylight to the west of me. Also, the antenna had an east-west orientation, meaning that it would get out the best to the north and south, which explains the good signal into Texas and Louisiana.

If you see your call sign here, thanks for the contact. And if you don’t see your call sign here (or if you don’t have a call sign yet), I look forward to seeing you on the air next year! Maybe by then I’ll try out QRP Labs’ QDX digital transceiver. Starting for just $69, it’s a multi-band digital transceiver. It plugs into your computer, and you can immediately start bouncing your signals off the ionosphere into other states and countries. If you get the entry-level technician license, you can use it immediately on 10 meters. While that band is very hot right now, that’s not always the case. Therefore, I would recommend also taking the test for the slightly more difficult general class license. But you’re in luck, as I’m also the author of a study guide for that test.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after following the link.

about his experiences living in Kyiv, Ukraine, in the middle of a war. Wlad, like me, is an attorney, and lived a middle-class existence similar to mine, until Russia invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014. He and his family then relocated to Kyiv, but with Russia’s 2022 invasion, he was once again in the middle of the war. His wife and teen son and daughter evacuated to Poland, where they were able to find an apartment, thanks in part to the generosity of friends in America and elsewhere.

about his experiences living in Kyiv, Ukraine, in the middle of a war. Wlad, like me, is an attorney, and lived a middle-class existence similar to mine, until Russia invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014. He and his family then relocated to Kyiv, but with Russia’s 2022 invasion, he was once again in the middle of the war. His wife and teen son and daughter evacuated to Poland, where they were able to find an apartment, thanks in part to the generosity of friends in America and elsewhere.