Pierre H. Boucheron was obviously our kind of people, as evidenced by his article a hundred years ago this month in the May 1920 issue of Electrical Experimenter, entitled “A One Tube Radio-Telegraph and Radio-Phone Transmitter.” It appears that Boucheron was on the cutting edge of radio technology. He starts his article by noting: “Amateurs, do you realize that a great deal of interesting experimenting is at the present day done by many amateurs all over the country employing undampt (in other words, CW, rather than spark) transmission? For the most part this is being accomplisht by the use of one or more vacuum tubes on oscillating circuits well below two hundred meters (in other words, above 1500 kHz). This is possibly one of the reasons why you do not hear them. Another reason is that it is continuous wave and not readily intercepted when ordinary dampt wave receivers are employed.”

Pierre H. Boucheron was obviously our kind of people, as evidenced by his article a hundred years ago this month in the May 1920 issue of Electrical Experimenter, entitled “A One Tube Radio-Telegraph and Radio-Phone Transmitter.” It appears that Boucheron was on the cutting edge of radio technology. He starts his article by noting: “Amateurs, do you realize that a great deal of interesting experimenting is at the present day done by many amateurs all over the country employing undampt (in other words, CW, rather than spark) transmission? For the most part this is being accomplisht by the use of one or more vacuum tubes on oscillating circuits well below two hundred meters (in other words, above 1500 kHz). This is possibly one of the reasons why you do not hear them. Another reason is that it is continuous wave and not readily intercepted when ordinary dampt wave receivers are employed.”

He went on to point out that there were hotbeds of such activity in places such as New York, Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, Chicago, New Orleans, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. He pointed out that ranges of five miles were easy on 100 meters (3 MHz), and offered a number of circuits to get on the air.

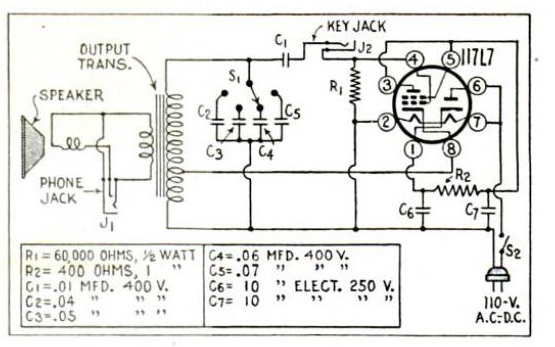

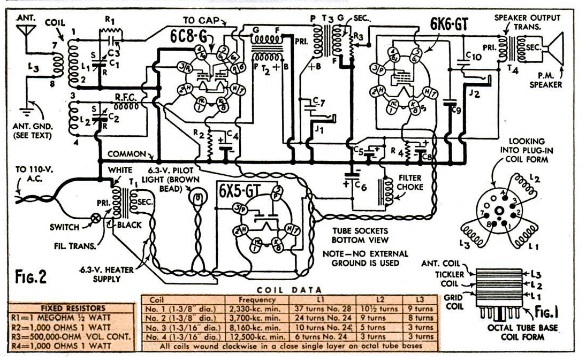

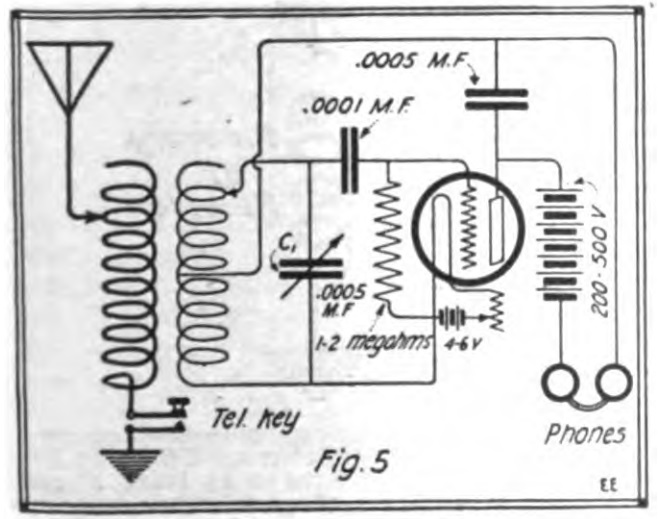

One of the most intriguing is shown above. It’s a single tube regenerative receiver, suitable for pulling in CW signals. But since it can quickly be adjusted to oscillate, a key between the antenna coil and ground would turn it into a transmitter.

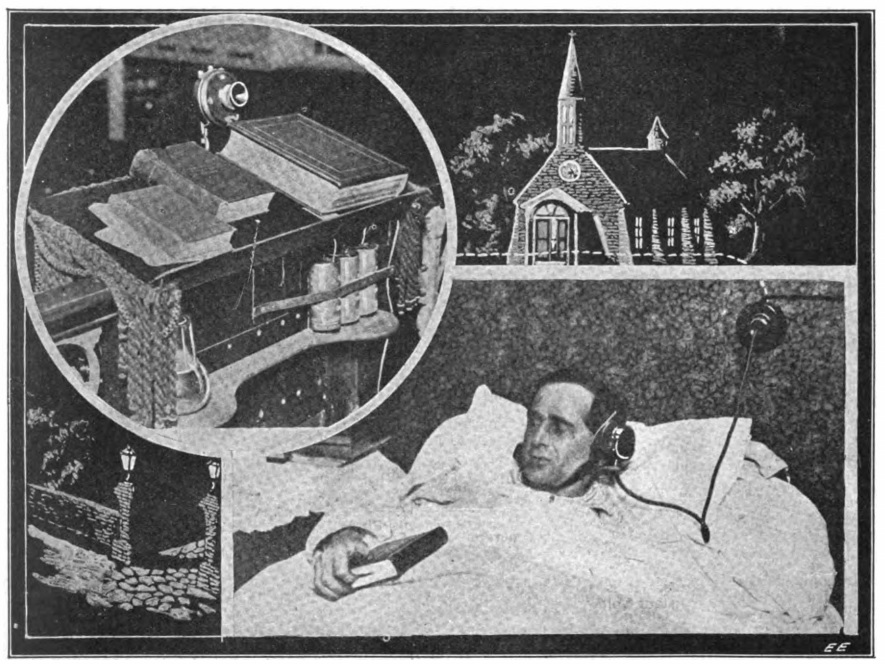

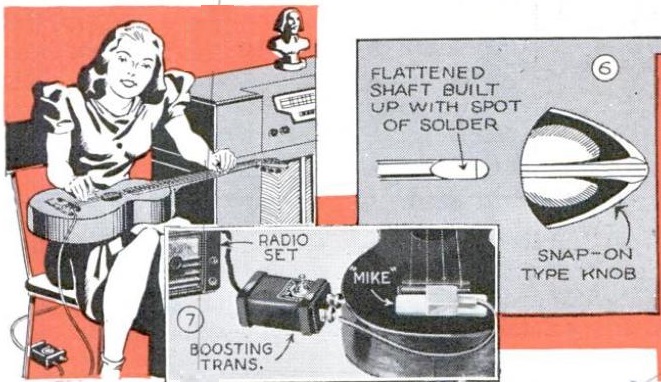

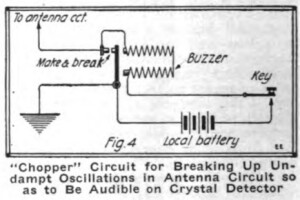

Another interesting idea is the one shown at the left. If you own an audion, but your buddy across town doesn’t, it’s possible to turn your undamped CW signals into faux spark signals. A buzzer is simply placed in series with the antenna circuit of your transmitter. When it’s keyed, the antenna is interrupted many times per second. The result is a signal modulated at the frequency of the buzzer, which can be picked up by your buddy with a crystal detector.

Another interesting idea is the one shown at the left. If you own an audion, but your buddy across town doesn’t, it’s possible to turn your undamped CW signals into faux spark signals. A buzzer is simply placed in series with the antenna circuit of your transmitter. When it’s keyed, the antenna is interrupted many times per second. The result is a signal modulated at the frequency of the buzzer, which can be picked up by your buddy with a crystal detector.