The Novice Class license was first authorized by the FCC effective July 1, 1951. Actually, July 1 was a Sunday, so the first exams probably took place on July 2, with the licenses arriving several weeks thereafter. Novices were allowed to operate initially on CW on 80 meters (3700-3750 kHz) and on the old 11 meter band (26.96-27.23 MHz), as well as both CW and ‘phone on 2 meters (145-147 MHz). The June 1951 issue of QST carried a feature “How To Pass the Novice Examination,” and included the 28 question study guide for the 20 question multiple-choice test.

The Novice Class license was first authorized by the FCC effective July 1, 1951. Actually, July 1 was a Sunday, so the first exams probably took place on July 2, with the licenses arriving several weeks thereafter. Novices were allowed to operate initially on CW on 80 meters (3700-3750 kHz) and on the old 11 meter band (26.96-27.23 MHz), as well as both CW and ‘phone on 2 meters (145-147 MHz). The June 1951 issue of QST carried a feature “How To Pass the Novice Examination,” and included the 28 question study guide for the 20 question multiple-choice test.

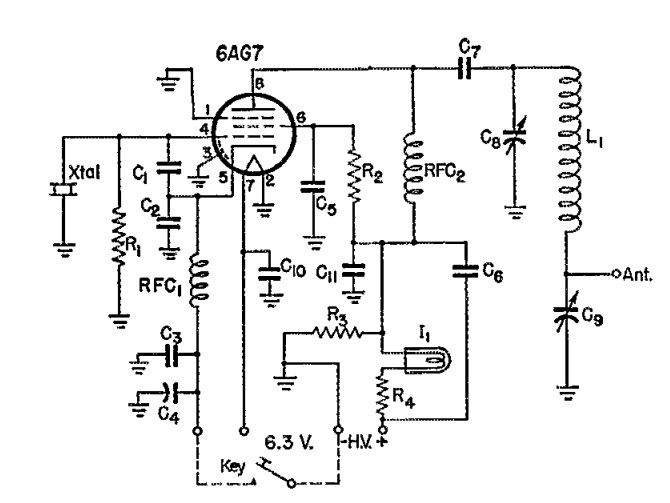

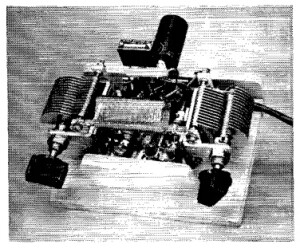

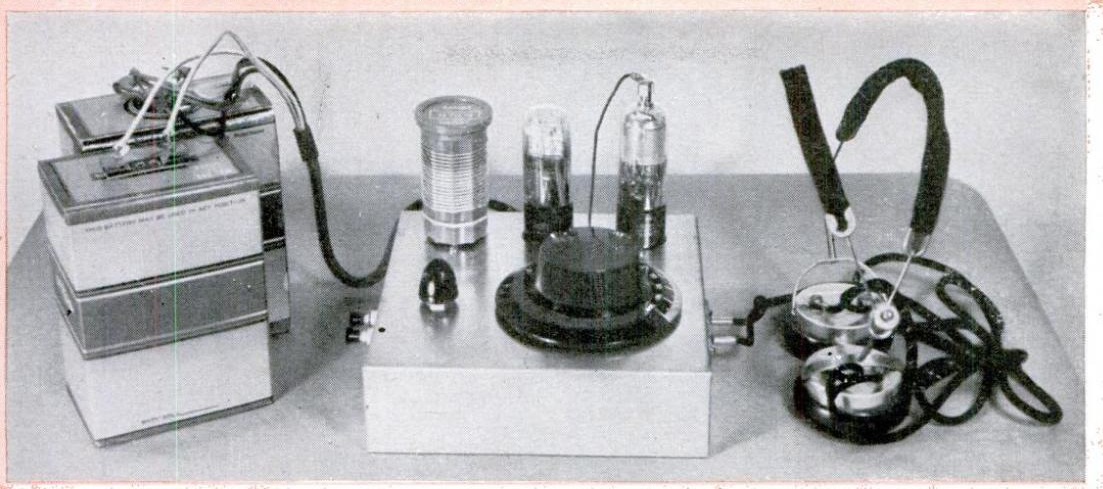

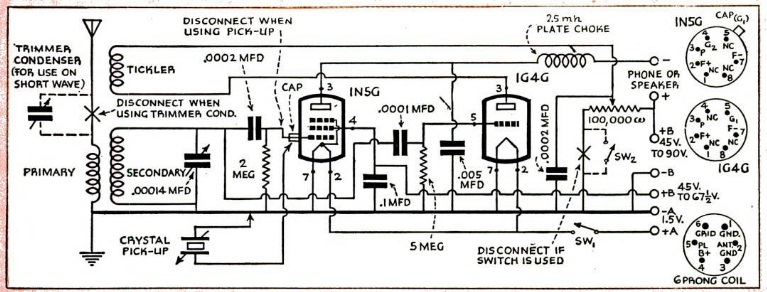

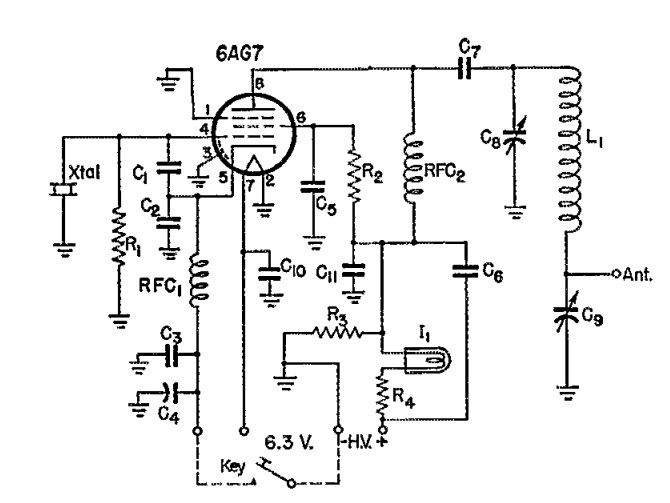

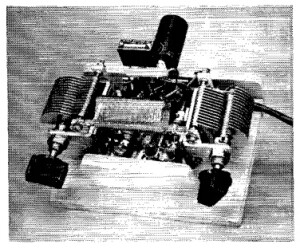

The May and June issues also carried the plans for a simple transmitter for the novice to get on the air. The set was designed by ARRL Technical Editor Don Mix, W1TS, who pointed out that a higher power transmitter, or one on the 11 meter band, might require additional shielding or other precautions to avoid television interference. The simple circuit here, however, was capable of contacts even with an antenna as short as five feet, although longer was, of course, recommended. The retail cost of all of the transmitter components was only $15, and the set required only four hand tools to put together: screwdriver, pliers, hand saw, and soldering iron. The chassis consisted of a board, and the tube socket was mounted horizontally on two metal angle pieces.

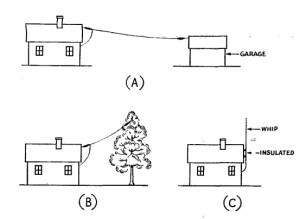

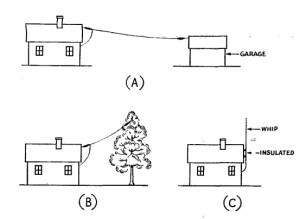

The May issue showed how to put together the transmitter, and the June issue showed an accompanying power supply as well as ideas for an antenna. The author reported that with brief tests from West Hartford, Connecticut, he was able to put stations in Wisconsin and Florida in the log at night, with Maine and Pennsylvania during the day. The set was designed to run to a random wire, and some ideas for the transmitting antenna are shown here. A long outdoor antenna was, of course, recommended, but if necessary, and indoor antenna could be used, and the set would load up into an antenna as short as five feet.

The May issue showed how to put together the transmitter, and the June issue showed an accompanying power supply as well as ideas for an antenna. The author reported that with brief tests from West Hartford, Connecticut, he was able to put stations in Wisconsin and Florida in the log at night, with Maine and Pennsylvania during the day. The set was designed to run to a random wire, and some ideas for the transmitting antenna are shown here. A long outdoor antenna was, of course, recommended, but if necessary, and indoor antenna could be used, and the set would load up into an antenna as short as five feet.

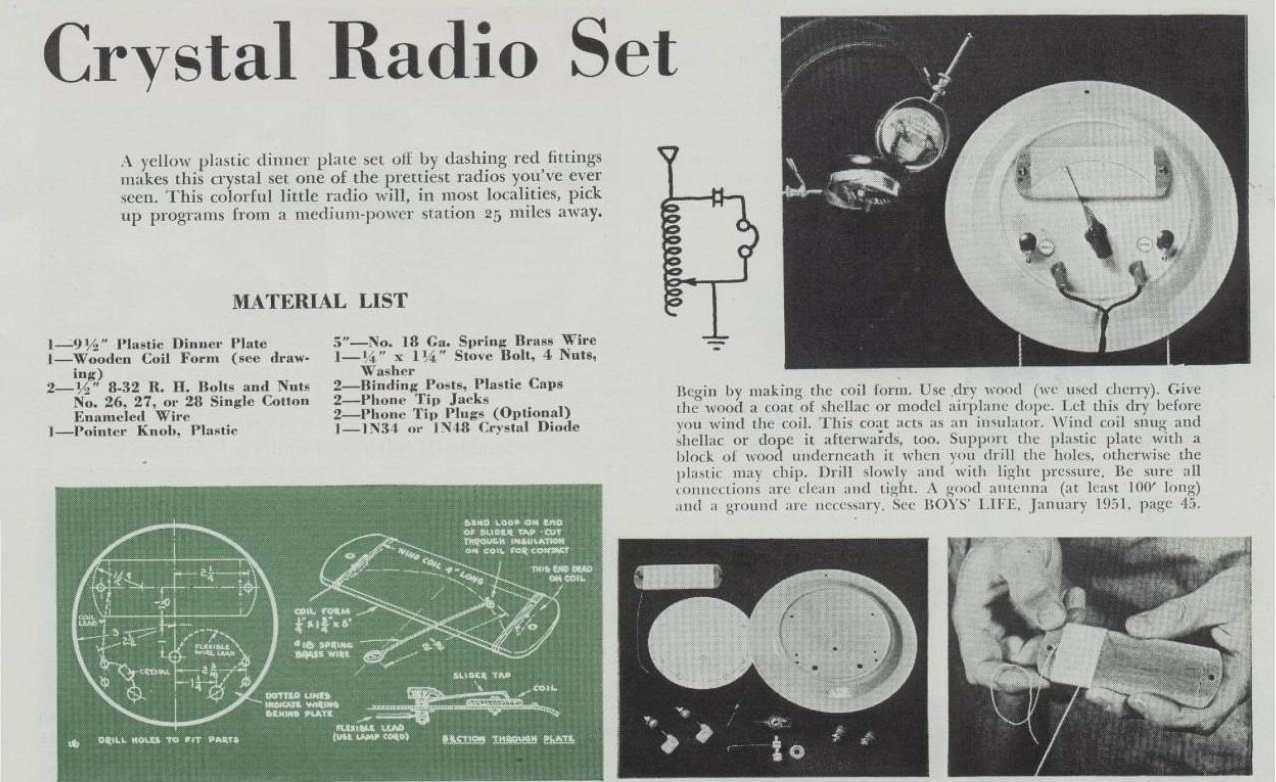

Seventy years ago, the May 1951 issue of Boys’ Life carried these plans for “one of the prettiest radios you’ve ever seen.” The chassis was a plastic dinner plate, and the magazine specified that the dish should be yellow, with dashing red fittings. With a good antenna (at least 100 feet) and ground, the set would pull in medium power stations up to 25 miles away.

Seventy years ago, the May 1951 issue of Boys’ Life carried these plans for “one of the prettiest radios you’ve ever seen.” The chassis was a plastic dinner plate, and the magazine specified that the dish should be yellow, with dashing red fittings. With a good antenna (at least 100 feet) and ground, the set would pull in medium power stations up to 25 miles away.