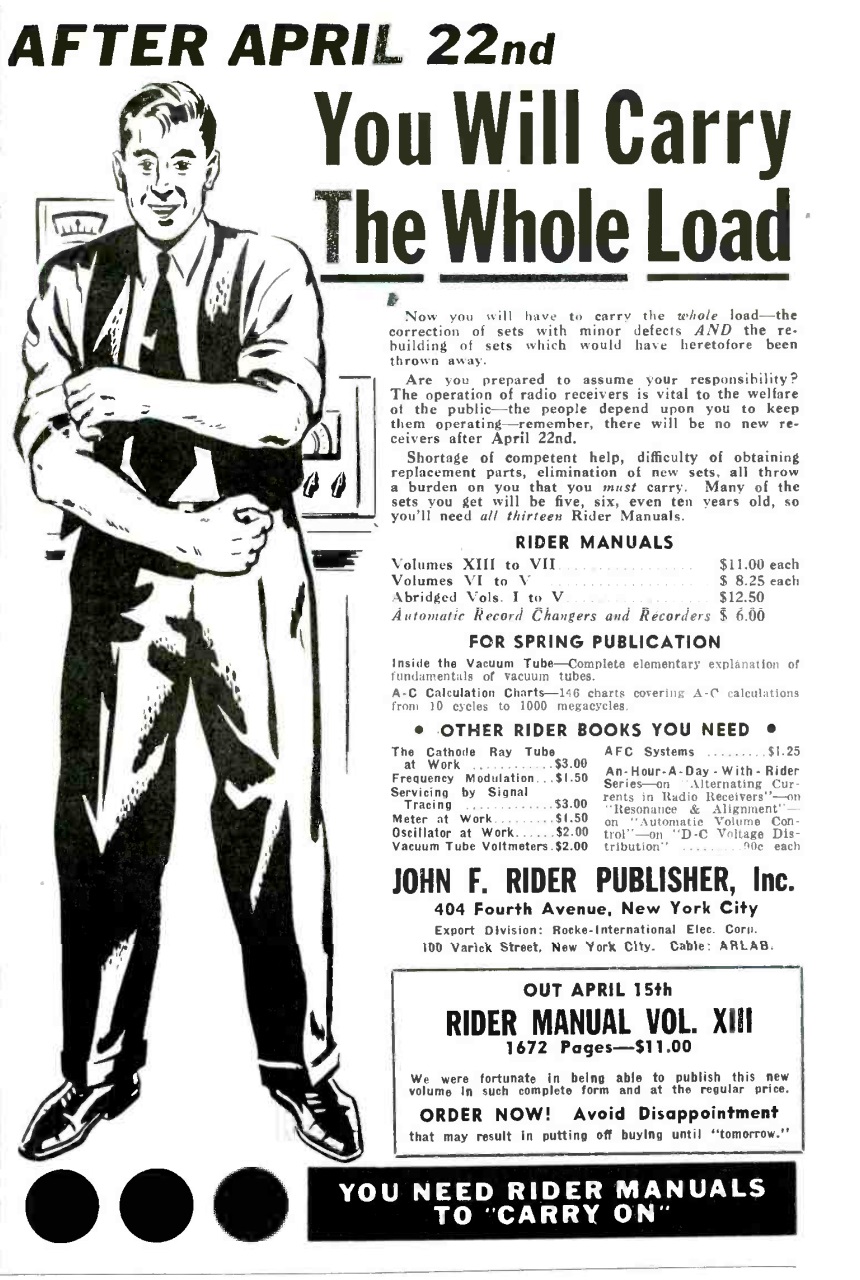

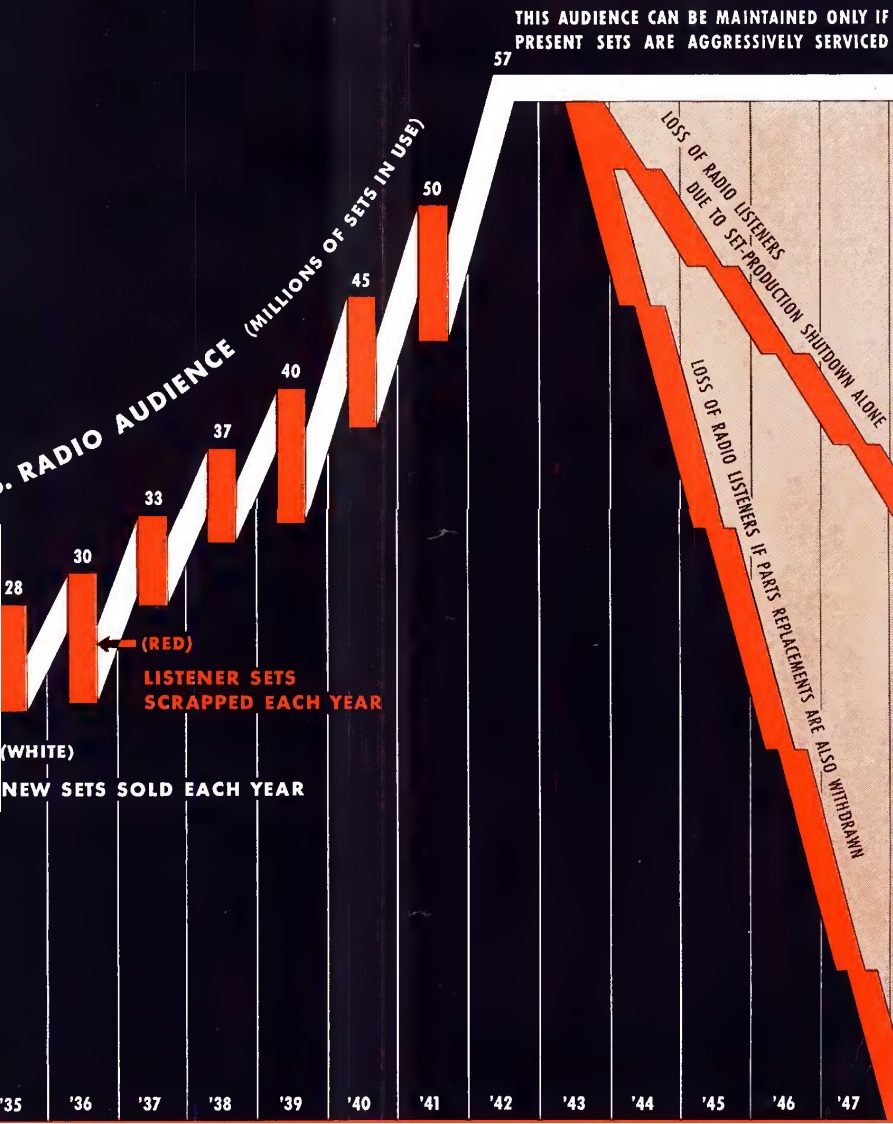

As we’ve previously reported, civilian radio production in the United States ended for the duration of the war on April 22, 1942. The graph above, which appeared on the cover of the April 1942 issue of Radio Retailing, showed how critical the radio repairman would be to keep the nation informed. As of that date, there were 57 million radios in American homes. In the years prior to the war, about 10 million new sets were made each year, but about 5 million old sets were scrapped by their owners each year, for a net increase of about 5 million.

As we’ve previously reported, civilian radio production in the United States ended for the duration of the war on April 22, 1942. The graph above, which appeared on the cover of the April 1942 issue of Radio Retailing, showed how critical the radio repairman would be to keep the nation informed. As of that date, there were 57 million radios in American homes. In the years prior to the war, about 10 million new sets were made each year, but about 5 million old sets were scrapped by their owners each year, for a net increase of about 5 million.

With the end of production, the supply would remain at 57 million for the duration–but only if every radio was kept in service. If the prewar trend of 5 million radios per year being scrapped continued, then the number would be as shown in the graph at the right. And if repair parts became unavailable, then the situation would be even worse. The supply of radios would plummet, as shown by the steeply declining graph.

The message was clear: To keep the American public informed, dealers would need to concentrate their efforts on repairs, and manufacturers and the government would need to make sure that repair parts remained available.