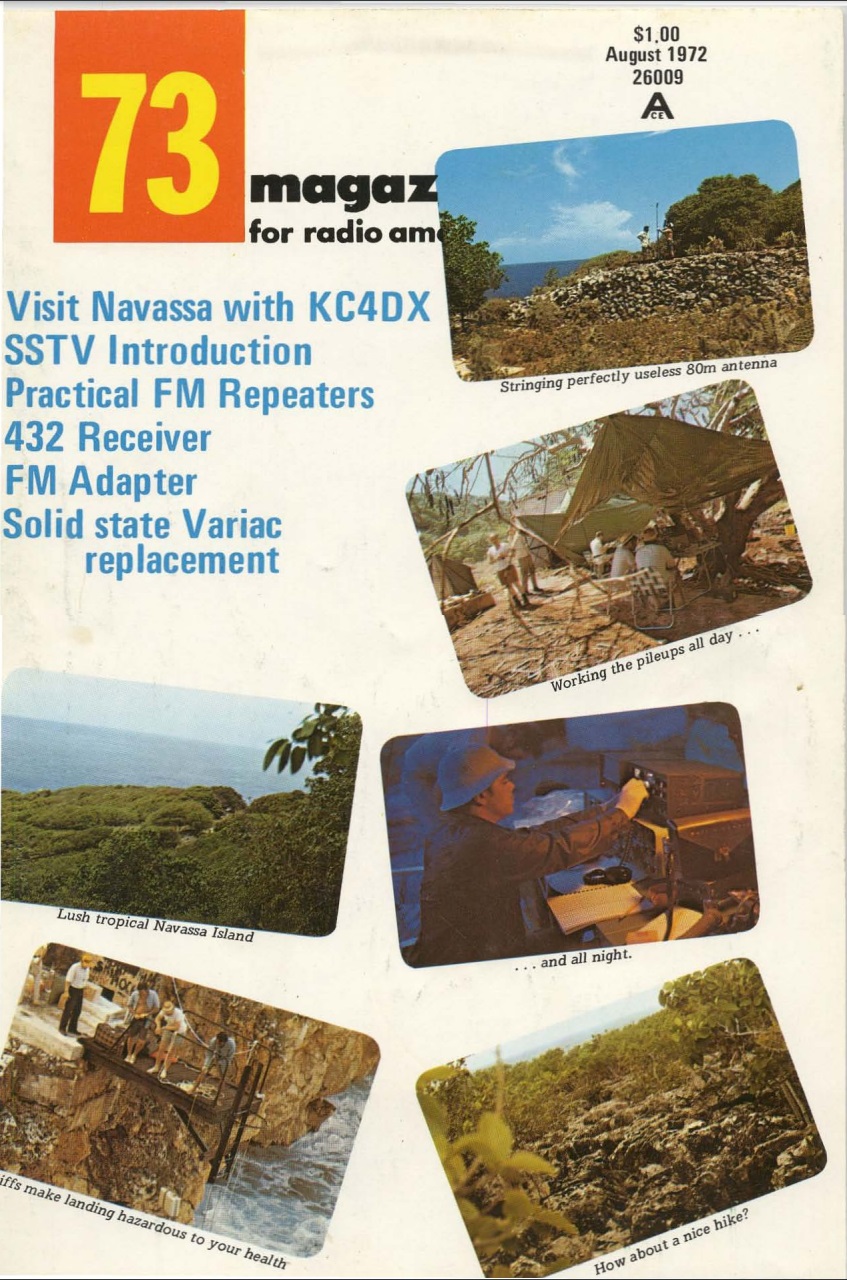

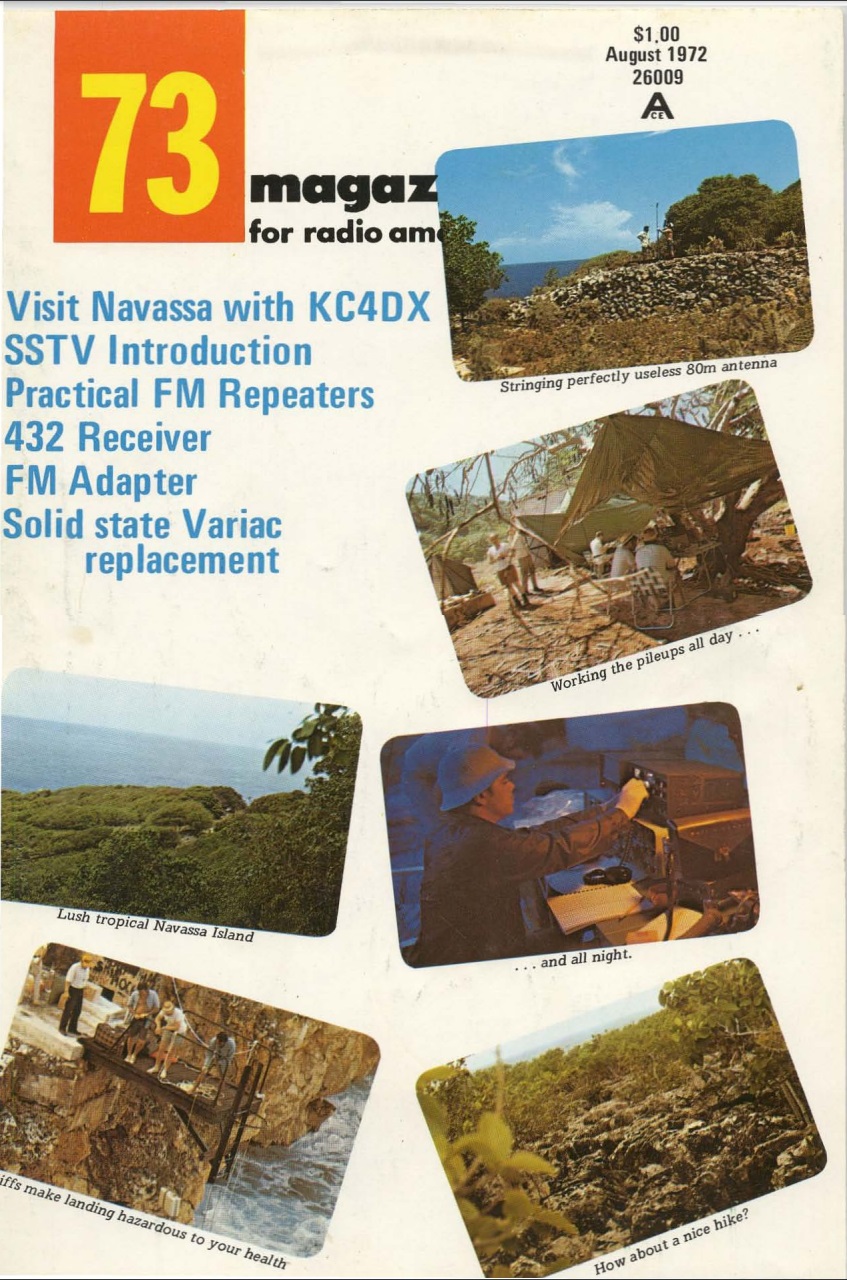

Fifty years ago this month, the August 1972 issue of 73 magazine devoted its cover and an extensive article to the May 12-15, 1972 KC4DX DXpedition to Navassa Island, a two-square-mile island nestled in the Caribbean between Cuba, Haiti, and Jamaica. The island is a U.S. possession, although also claimed by Haiti. Surrounded by cliffs on all sides, it has no beaches, and the only access by sea is a wire ladder dangling down from a platform cantilevered over one of the cliffs.

Fifty years ago this month, the August 1972 issue of 73 magazine devoted its cover and an extensive article to the May 12-15, 1972 KC4DX DXpedition to Navassa Island, a two-square-mile island nestled in the Caribbean between Cuba, Haiti, and Jamaica. The island is a U.S. possession, although also claimed by Haiti. Surrounded by cliffs on all sides, it has no beaches, and the only access by sea is a wire ladder dangling down from a platform cantilevered over one of the cliffs.

The magazine’s publisher, Wayne Green, had done a DXpedition to the island in 1958 with the call KC4AF, and when he caught wind of plans to go in 1972, he signed on as photographer.

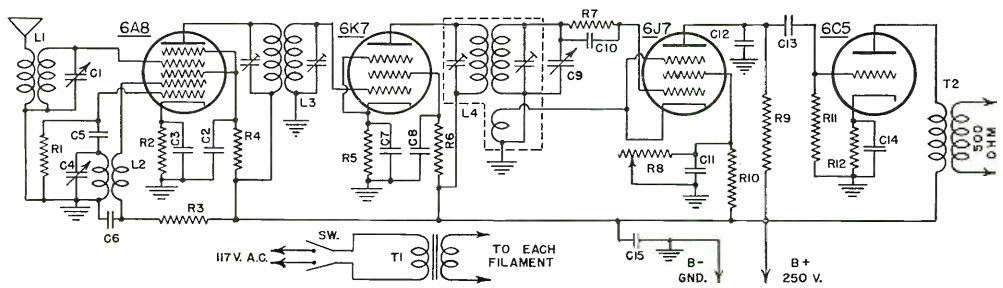

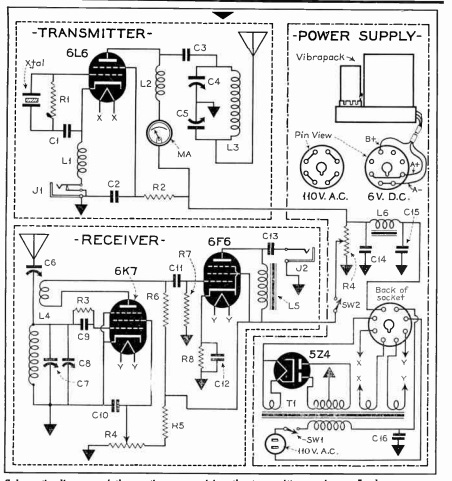

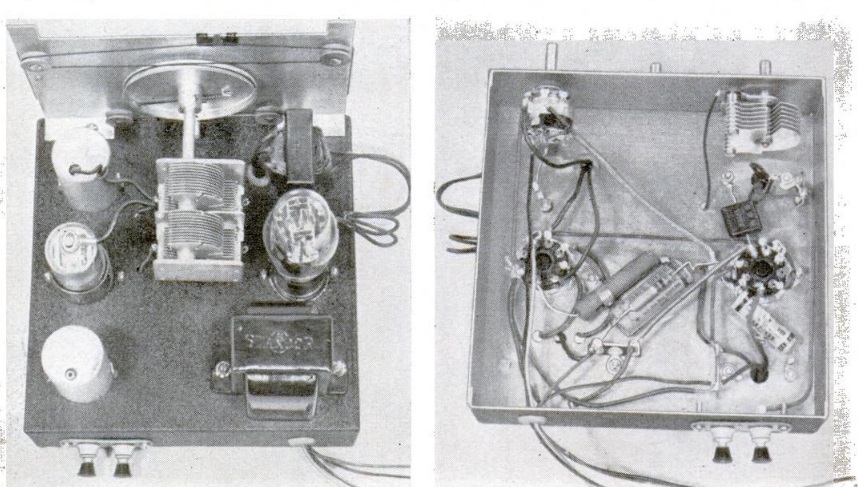

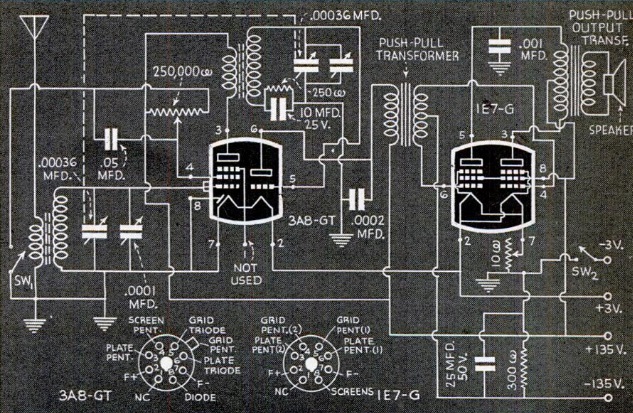

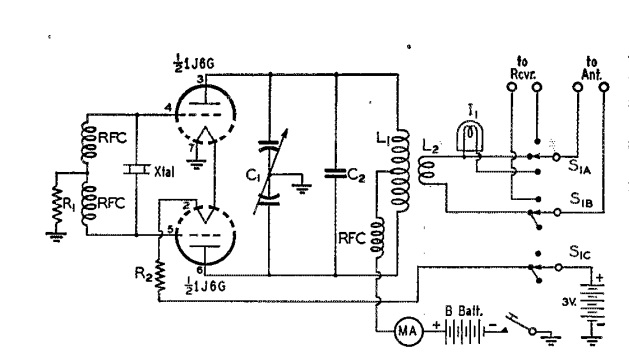

The 1972 expedition used only three radios, a Swan 500C transceiver, as well as a pair of Heathkit SB303 receiver/SB401 transmitter. Two gasoline generators powered the stations, which operated for only 54 hours. The Swan transceiver was incapable of “split” operation. That, coupled with the fact that only modest antennas were used, hampered the operation somewhat, although 5500 contacts made it into the log.

In addition to the 73 article, which you can read at the link above, you can find this account, complete with some videos, by W4GKF.

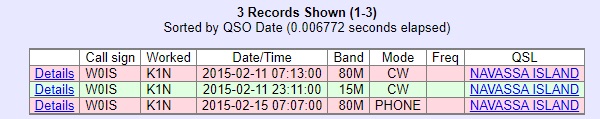

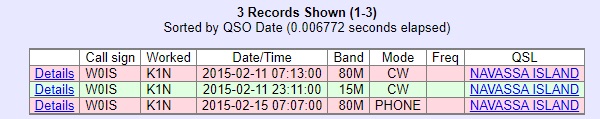

At the time of the 1972 operation, the island was under the control of the U.S. Coast Guard, who still operated a lighthouse there. It was last activated in about 1997 until a 2015 DXpedition, K1N, again put it on the air. By this time, the island was administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which had traditionally been reluctant to allow civilians on the island. This, however, was arranged, and the operators and equipment were brought in by helicopter, since the famous ladder had been removed when USFWS took over administration. This time, 140,000 contacts were made, with 30,000 different stations. As you can see, I made it in the log in 2015:

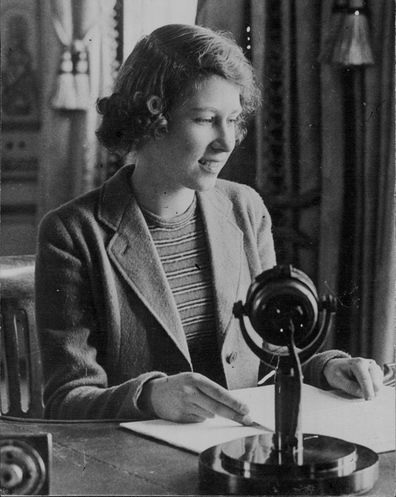

Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom died today at the age of 96. She was preceded in death by her husband Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, Patron of the Radio Society of Great Britain.

Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom died today at the age of 96. She was preceded in death by her husband Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, Patron of the Radio Society of Great Britain.