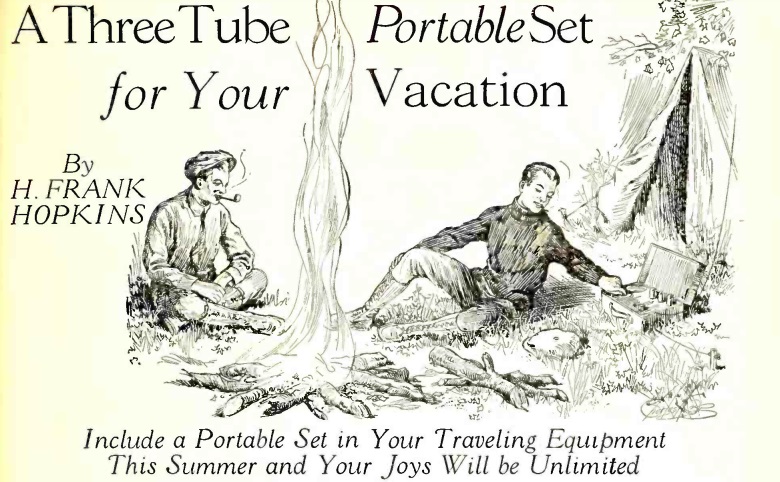

101 years ago, this duo were camped out in the great outdoors. After a day of adventures, they were able to tune in some music, or perhaps listen to the news of the world, thanks to the foresight of bringing along a radio. And for the 1925 season, the April 1925 issue of Radio Age showed how to build the set.

101 years ago, this duo were camped out in the great outdoors. After a day of adventures, they were able to tune in some music, or perhaps listen to the news of the world, thanks to the foresight of bringing along a radio. And for the 1925 season, the April 1925 issue of Radio Age showed how to build the set.

The author began poetically by quoting a portion of The Call of The Wild by Robert W. Service:

Have you seen God in His splendors,

Heard the text that nature renders?

(You’ll never hear it in the family pew.)

The simple things, the true things,

The silent men who do things –

Then listen to the Wild –

It’s calling you.

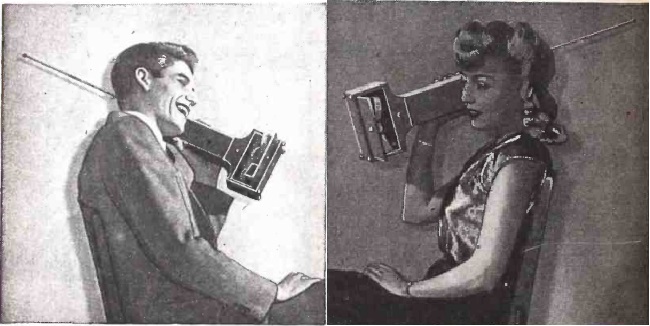

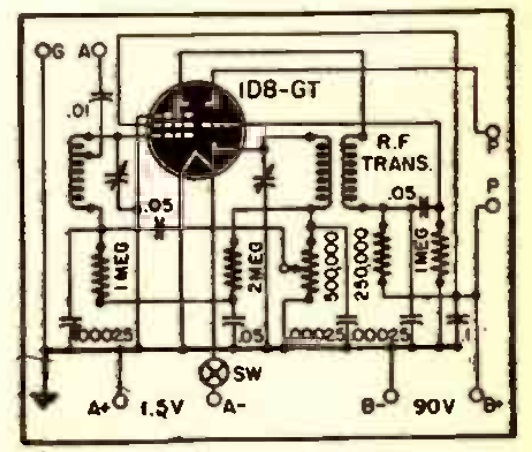

And the best way to pull in the call of the wild is with a three-tube TRF set, as described in the article. The set was said to pull in DX, and the next step up would be a much more complex superheterodyne. This set was a moderate priced, good, substantial receiver, in a compact case containing batteries and loudspeaker.

Setting it up was simple. Just find a tree 50 feet away from the desired location, get the end of the antenna up as high as possible, and run it to the set. A tent pole would serve as a suitable mast for that end of the wire.

For modern campers, we recommend a small portable such as the one shown here. Like everything, it’s available inexpensively at Amazon. In addition to AM and FM broadcasts, it will pull in the shortwaves, meaning that almost anywhere you find yourself in the world, you’ll find something to listen to. And if you’re in North America, you’ll be able to get NOAA weather broadcasts. It’s powered by AAA batteries, but you can also run it from the built-in hand crank or solar panel. You can even use it to charge your phone or other USB device, and it has a built-in flashlight and siren. And you can even pull in the Call of The Wild.

For modern campers, we recommend a small portable such as the one shown here. Like everything, it’s available inexpensively at Amazon. In addition to AM and FM broadcasts, it will pull in the shortwaves, meaning that almost anywhere you find yourself in the world, you’ll find something to listen to. And if you’re in North America, you’ll be able to get NOAA weather broadcasts. It’s powered by AAA batteries, but you can also run it from the built-in hand crank or solar panel. You can even use it to charge your phone or other USB device, and it has a built-in flashlight and siren. And you can even pull in the Call of The Wild.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

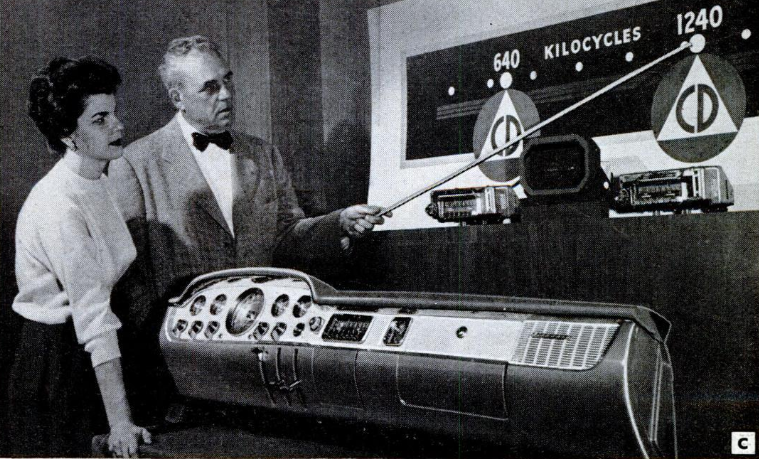

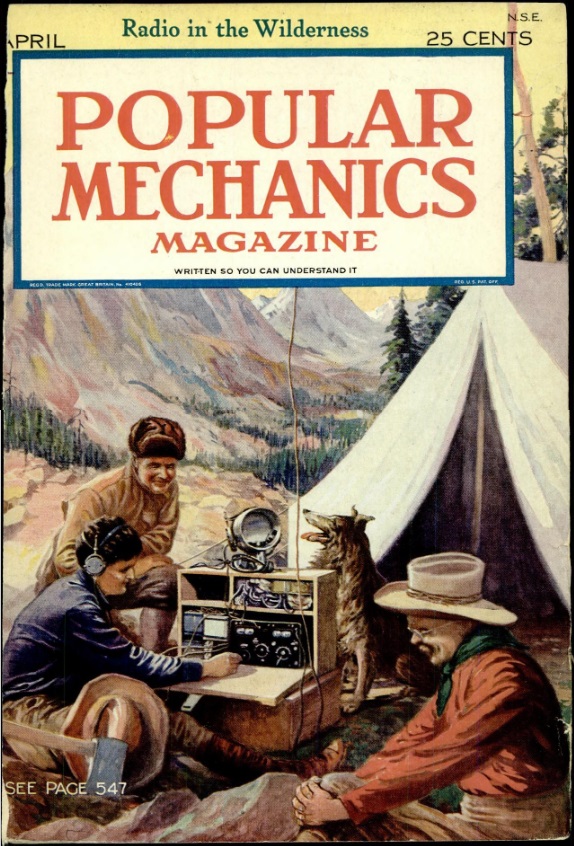

A hundred years ago this month, the cover of the April 1925 issue of Popular Mechanics shows author Lewis R. Freeman and his companions at the controls of a four-tube radio set during an expedition to the Canadian Rockies. In 1923, he had taken a radio to the Grand Canyon and successfully pulled in stations, despite assurances by so-called experts that reception would be impossible. Emboldened, he was asked to join the Canadian expedition, and brought along the four-pound radio. Batteries and other accessories added forty pounds.

A hundred years ago this month, the cover of the April 1925 issue of Popular Mechanics shows author Lewis R. Freeman and his companions at the controls of a four-tube radio set during an expedition to the Canadian Rockies. In 1923, he had taken a radio to the Grand Canyon and successfully pulled in stations, despite assurances by so-called experts that reception would be impossible. Emboldened, he was asked to join the Canadian expedition, and brought along the four-pound radio. Batteries and other accessories added forty pounds.

For modern campers, we recommend a small portable such as the one shown here. Like everything, it’s

For modern campers, we recommend a small portable such as the one shown here. Like everything, it’s