Seventy five years ago this month, the June 1944 issue of Popular Mechanics carried a lesson in the now almost forgotten art of reading a vernier scale. With virtually any kind of instrument with an analog display, such as a caliper or micrometer, the vernier scale allows the human eye to make a much more precise reading.

Seventy five years ago this month, the June 1944 issue of Popular Mechanics carried a lesson in the now almost forgotten art of reading a vernier scale. With virtually any kind of instrument with an analog display, such as a caliper or micrometer, the vernier scale allows the human eye to make a much more precise reading.

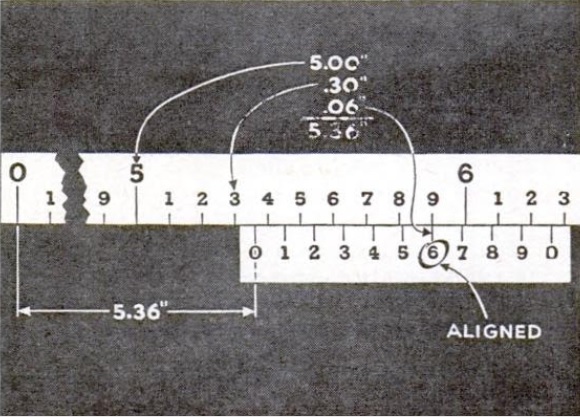

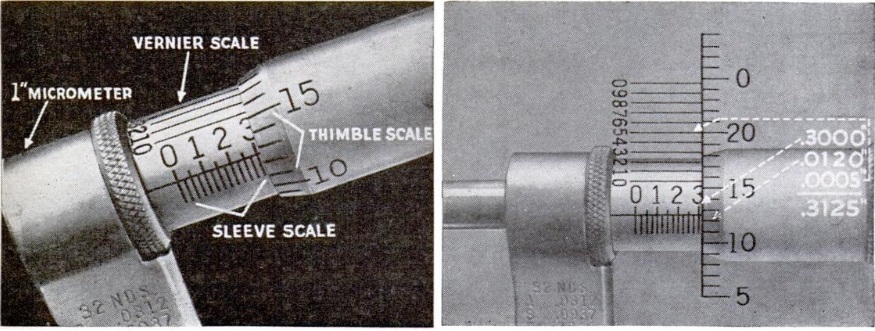

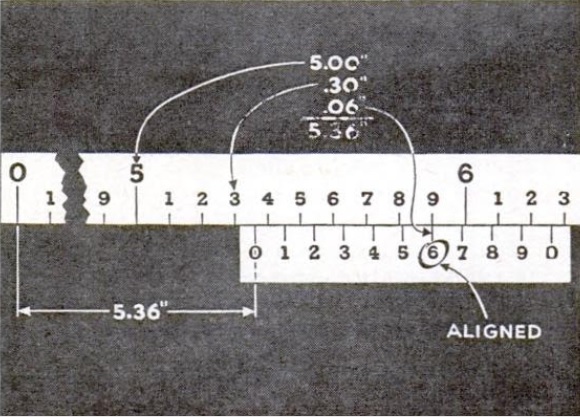

The vernier display consists of two scales. In the example shown above, the top scale is the main scale, and shows just over 5.3 inches. (The zero on the bottom scale takes the place of the pointer which would be used on a non-vernier scale.)

The human eye, looking at this pointer, would undoubtedly conclude that the actual measurement is 5.35 inches, since the pointer is about halfway between the 3 and the 4. But is it really 5.35, or is it 5.34 or 5.36? You can’t really tell with the naked eye.

But the vernier scale makes eyeballing it easy. You simply look at the bottom scale, and see which number is exactly lined up (or most closely lined up) with a number above. In this example, the 6 on the bottom scale is lined up exactly with the 9 on the upper scale. The number on the upper scale is not important–it’s only important that some number on the lower scale is lined up exactly. In this case, the 6 means that we add 6/100 inch, meaning that the exact measurement is 5.36″.

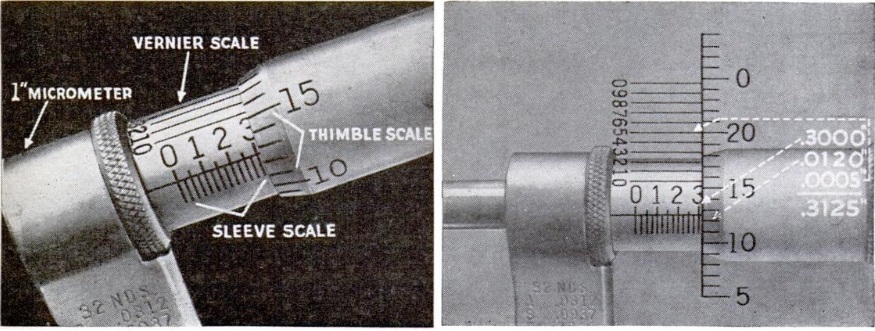

Below, we see a vernier dial applied to a caliper. In the picture on the right, the scales are flattened so that they can be viewed on the printed page. The idea is the same. The sleeve scale shows 0.3 inch, plus 0.12 on the thimble scale, since the center line is between 12 and 13. The 5 on the vernier scale is lined up with the 20, meaning that we add .005 inch. Thus, the measurement is .3 + .012 + .005 = .3125 inches.

Radio fans are probably most familiar with the “vernier dial” shown at the left. This one is available on Amazon and is called a “vernier dial.” However, the vernier markings which are supposed to be on the tab on top are inexplicably missing.

Radio fans are probably most familiar with the “vernier dial” shown at the left. This one is available on Amazon and is called a “vernier dial.” However, the vernier markings which are supposed to be on the tab on top are inexplicably missing.

The vernier scale is named after vernier acuity, the human eye’s ability to detect small differences in the alignment of a straight line.

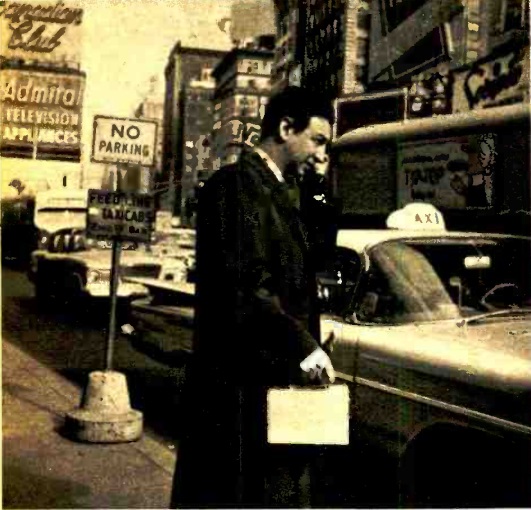

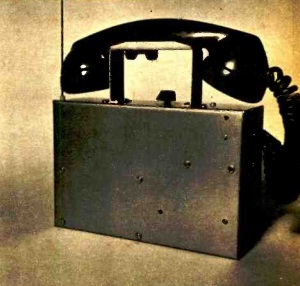

The gentleman shown here is obviously a mover and shaker, and he’s staying in touch thanks to a portable citizen’s band transceiver that he assembled himself from a semi-kit. The electronics came pre-wired, but he had to do the final assembly himself, a process that took about three hours.

The gentleman shown here is obviously a mover and shaker, and he’s staying in touch thanks to a portable citizen’s band transceiver that he assembled himself from a semi-kit. The electronics came pre-wired, but he had to do the final assembly himself, a process that took about three hours.