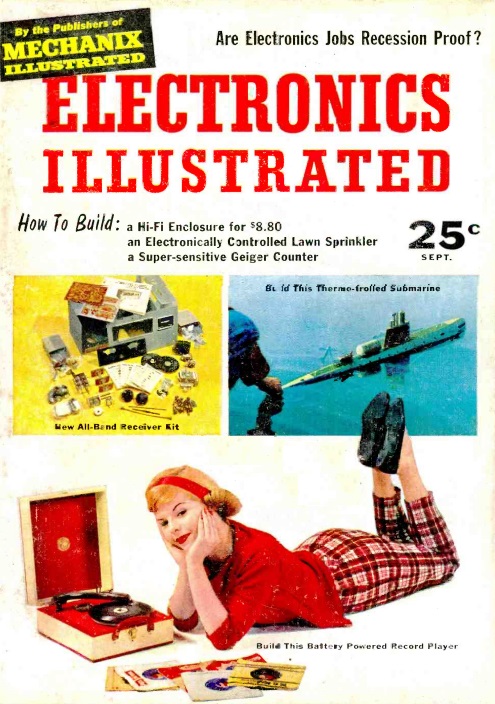

The young woman shown here on the cover of the September 1958 issue of Electronics Illustrated is listening wistfully to some music courtesy of the portable phonograph she constructed according to the plans contained in that issue.

The young woman shown here on the cover of the September 1958 issue of Electronics Illustrated is listening wistfully to some music courtesy of the portable phonograph she constructed according to the plans contained in that issue.

She was able to put the project together in just a few hours, and it allowed her to listen to music wherever she pleased, thanks to the fact that the set ran entirely on batteries. Both the motor (three speeds–45, 33, and 16 RPM) and the amplifier were powered by four flashlight batteries, and the completed phonograph was no larger than a small overnight bag, light enough for a child to carry.

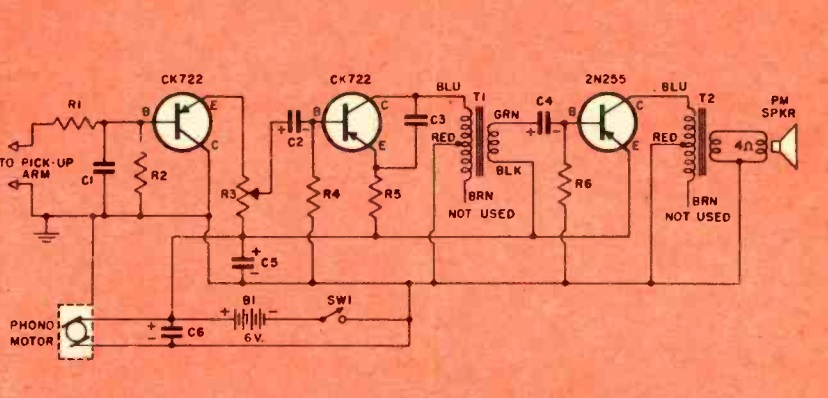

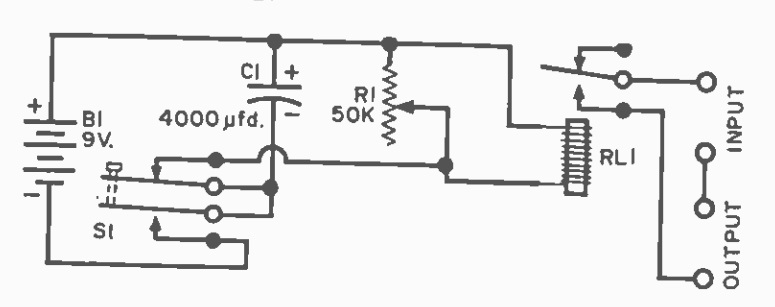

The circuit consisted of two CK722 transistors, as well as a 2N255 mounted on a heatsink, which provided enough power to drive the speaker. Volume was said to be adequate for dancing and mood music, although the article pointed out that it was not a high fidelity instrument.

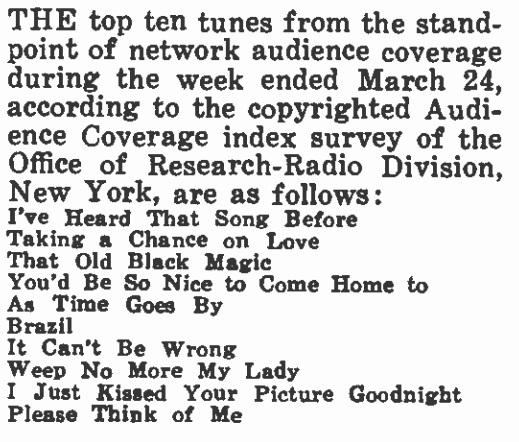

While there’s no way of knowing for sure, it’s likely that she is being entertained by a former Vice President of the United States. Topping the charts that month was “It’s All In The Game” performed by Tommy Edwards, which you can listen to in the video below.

Charles Dawes. Wikipedia image.

The melody of that song, originally unimaginatively entitled “Melody in A Major,” was composed in 1911 by Charles G. Dawes, who went on to become Vice President under Calvin Coolidge and earned the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925. Under President Hoover, Dawes served as ambassador to the United Kingdom. The song has the distinction of being the only number one single to have been composed by a Vice President of the United States. The Wikipedia entry for the song incorrectly states that the song is the only one to have been composed by a Nobel laureate, but the Dawes biography points out that this distinction is now shared with Bob Dylan. Dawes shares with Sonny Bono the distinction of being the only members of the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives to be credited with a number one hit.

In addition to being a banker, composer, diplomat, soldier, and politician, Dawes was a rather prolific author, as can be seen at his Amazon author page. A 2016 edition of his Journal of the Great War is still available.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gtizr2G_7Bk

Shown here in the mid-1920s are the

Shown here in the mid-1920s are the