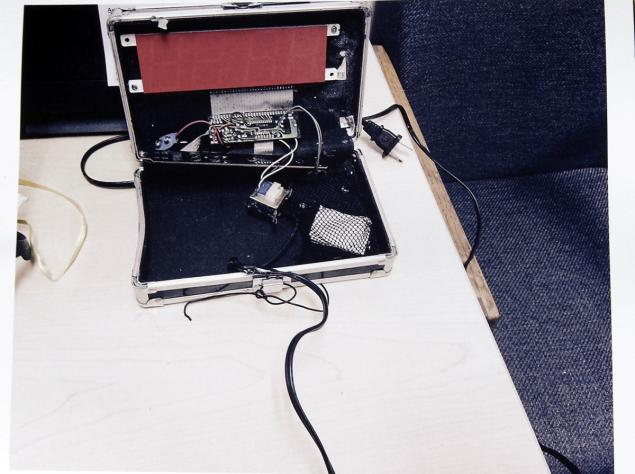

Today, I did a National Parks On the Air (NPOTA) activation of the North Country National Scenic Trail, a hiking trail that extends from eastern New York to North Dakota. My operating location was in Jay Cooke State Park, Minnesota, about 25 miles south of Duluth. My operating location is shown here. The radio itself, my Yaesu FT-817, is barely visible propped up by the bright blue canvas bag, in front of the dark blue bag. The 12 volt battery is on top of the bright red bag, and my lunch is inside the dark red bag. The cable going up to my antenna is visible, but the antenna, a 20 meter dipole tied to trees with string, while in the frame, is not visible.

Today, I did a National Parks On the Air (NPOTA) activation of the North Country National Scenic Trail, a hiking trail that extends from eastern New York to North Dakota. My operating location was in Jay Cooke State Park, Minnesota, about 25 miles south of Duluth. My operating location is shown here. The radio itself, my Yaesu FT-817, is barely visible propped up by the bright blue canvas bag, in front of the dark blue bag. The 12 volt battery is on top of the bright red bag, and my lunch is inside the dark red bag. The cable going up to my antenna is visible, but the antenna, a 20 meter dipole tied to trees with string, while in the frame, is not visible.

During NPOTA, amateur radio operators set up portable stations at National Park units and make contact with other amateurs at home. The event has been very popular, and there have been hundreds of thousands of contacts made from the parks. Since the event includes all units of the National Park Service, the North Country Trail qualifies as a “National Park,” allowing me to operate from one of the Minnesota state parks crossed by the trail.

During today’s activation, I managed only four contacts, the furthest being Mississippi. According to the Reverse Beacon Network, my signal was getting out. Unfortunately, many chasers don’t bother looking for stations. They wait until they’re spotted on the internet, and then work them. So making that first contact can be a challenge. Since I was only there for a brief stop over lunch, I didn’t bother persisting to make six more contacts. But I’ll be operating from this spot again on June 5 as part of the Light Up The Trail event being done in conjunction with NPOTA. During that event, stations will be set up at various locations along the North Country Trail. I decided to do a trial run today, since I’m in Duluth to present a Continuing Legal Education program on Friday morning, and then serving as a delegate to the Minnesota Republican State Convention on Friday and Saturday.

2012 flooding of bridge. USGS photo.

Swinging Bridge prior to 2012 flood. Wikipedia photo.

Jay Cooke State Park was originally created in 1915 by a donation of land from the St. Louis Power Company. It remained undeveloped until the 1930’s, when the Civilian Conservation Corps built many of the park’s structures, including the iconic Swinging Bridge over the St. Louis River. The bridge was destroyed by flooding in 2012 but subsequently rebuilt according to the original plans. As you can see from the picture at the top of the page, my operating location was near the bridge and near the River Inn visitor center in the picture shown below, also constructed by the CCC. The North Country Trail passes over the Swinging Bridge, putting my operating location well within the 50 yards from the trail required by the NPOTA rules.

River Inn Visitor Center, Jay Cooke State Park. Wikipedia photo.

This stretch of the St. Louis River consists of a long rapids impossible to traverse by canoe. Therefore, both Native Americans and Europeans portaged around the rapids, and this portage remained in use until the 1870’s.

Starting in the 17th century, the portage was used heavily by fur traders, since it formed part of the route from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River basin. The voyageurs had to traverse the 6.5 mile portage through the area, carrying two or three packs weighing about 90 pounds each. It took three to five days to cross the portage, and the voyageurs doing so would be covered with mud and insect bites. My activation today was not quite so strenuous. It required me to carry my complete station, including battery, radio, and antennas, weighing a total of about 10 pounds, a total of about 100 yards from the parking lot to the picnic area. And even though I got mostly skunked, I bet the voyageurs who traversed the area a few centuries ago would never dream that it would someday be possible to toss a wire into a tree and talk halfway across the continent with a piece of equipment that would have made only a small dent in their 90 pound packs.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()