We’ve previously written about how to prepare for a power outage. With a little preparation, you can live reasonably comfortably without electricity, and there are numerous inexpensive alternatives to provide yourself with light, power your electronic devices, and cook your food.

We’ve previously written about how to prepare for a power outage. With a little preparation, you can live reasonably comfortably without electricity, and there are numerous inexpensive alternatives to provide yourself with light, power your electronic devices, and cook your food.

News reports have warned of the possibility of power crises this summer, and most recently, Texans have been warned to conserve energy to prevent blackouts.

For many, a power outage in the summer would be an inconvenience, and mean having to go back to the days before air conditioning became universal. But a power outage in the winter could have life-threatening consequences. Of course, one can always evacuate and go to a place with power, but this might mean leaving the pipes in your house to freeze, potentially causing thousands of dollars in damage. Indeed, during the 2021 Texas power crisis, water service to a staggering 12 million persons was disrupted due to pipes freezing and bursting. When the pipes thawed, all of that water had to go somewhere, and it was often into the homes that had been without power. Plumbers were booked up solid, and building materials were simply unavailable. We had family members in Texas who had to deal with the aftermath of frozen pipes, and it served as a wake-up call. Since I live in Minnesota, sub-zero weather is common, and being without heat for just a few hours could prove extremely costly.

Of course, one possibility is to drain every pipe in the house, and then evacuate. But that’s extra work, we would need to find a place to stay, and there’s no guarantee that I would get every last drop out of the system. A better alternative is to provide a source of heat.

I decided that the best course of action would be to close off a good portion of the house. All of the plumbing in our house is in four rooms, all of which are contiguous–an upstairs bathroom and kitchen, and a downstairs bathroom and laundry room. Most other rooms can be closed off merely by closing a door. A downstairs family room can be closed off with a blanket, although it also contains a fireplace that could be used in an emergency. An upstairs living room and dining room would provide plenty of living space in an emergency.

Therefore, my plan for a winter power outage is to close off most of the house, meaning that only a relatively small area would need to be heated. For a long-term power outage, we do have a generator, and it could be used to run the electrical portion of our gas furnace. However, I would need to go in and re-wire it, disconnect it from the house, and connect that circuit to an extension cord (since we don’t have a transfer switch).

A Portable Propane Heater

simpler option, however, which does not require firing up the generator, is to use a portable propane heater. To heat the house in an emergency, I recently acquired a Mr. Heater portable propane heater like the one shown above. Unlike many propane heaters, it is specifically designed for indoor use. In fact, in the event that oxygen levels get dangerously low, it automatically shuts off. I only have one, but I think by moving it from room to room periodically, it should keep the house somewhat comfortable, or at least keep all of the pipes above freezing. Obviously, it’s not going to provide as much heat as the normal furnace, but I think it’s large enough for the bare minimum of emergency heating.

Since we have a gas water heater that does not require any electricity whatsoever, my plan is to keep all of the faucets dripping with warm water. The moving water will keep those pipes from freezing, and a certain amount of heat will be radiated from the hot water pipes. In addition, the gas stove in the kitchen will be used for cooking as usual, and the “waste” heat from this process will help warm the house. While possible, loss of natural gas is much less common than loss of electricity. The water heater will keep operating seamlessly without electricity, but the kitchen stove will require matches to light. (The oven will not work without electricity.)

The propane heater needs fuel. It’s designed to use the small one-pound cans of propane, like the ones shown here. For occasional use, these are quite handy, but they also get expensive, and they probably wouldn’t be available in an emergency.

The propane heater needs fuel. It’s designed to use the small one-pound cans of propane, like the ones shown here. For occasional use, these are quite handy, but they also get expensive, and they probably wouldn’t be available in an emergency.

According to this site, a one-pound bottle will last about 5 hours on low, or about two hours on high. So if was run constantly, it would require, at a minimum, about 5 bottles per day, which would get expensive very fast.

Using Less Expensive 20 Pound Propane Bottles

Propane in 20 pound bottles is much cheaper. And those large bottles are available at many convenience stores, hardware stores, and even the local drug store.

Propane in 20 pound bottles is much cheaper. And those large bottles are available at many convenience stores, hardware stores, and even the local drug store.

In normal circumstances, these propane exchange retailers aren’t the greatest deal. Generally, you pay for 20 pounds of propane and only get 15. So during normal circumstances, there are cheaper places to buy propane. But if an emergency is looming, the price isn’t too out of line, and there are many dealers close to home. In our case, we always have one bottle on hand, almost full, mounted on our camper. Others routinely have these on hand for their barbecue. According to that same website, 20 pounds of propane will last about 100 hours on low, or 40 hours on high. In other words, the single propane bottle we always have on hand will last between 2 and 4 days. And if I acted fast enough, I would be able to buy more very conveniently.

Refilling Propane Bottles

Refilling Propane Bottles

There are two ways to use the larger bottles with the Mr. Heater. The cheapest is to buy one of the little gadgets shown here, a propane refill adapter. What this allows you to do is to refill the one-pound bottles from the larger 20 pound bottle. It’s a bit of a cumbersome process, since you need to hook them up, and then turn the large bottle upside down for the propane to drain into the small canister. So it’s not ideal, but it’s cheap, and it works.

I should point out that this method is not entirely legal. In particular, you are not allowed to transport a “disposable” bottle, certainly not across state lines, after you have refilled it. That’s because the small bottle is designed for one use, and it might not seal up again. But for emergency use, it seems like a very small risk. Even though I’ll use the method shown below, I also have one of these refill valves. In some cases, it’s handier to use the small bottles, and I might want one of them for a propane lantern or stove. And if the hose shown below gets broken or misplaced, the refill kit is a good backup.

The better method, it seems to me, is to use the relatively inexpensive hose shown available from Mr. Heater. This is designed to be used with the Mr. Heater, and lets you run it directly from the larger 20 pound bottle. You no longer have to worry about the inconvenience and slight danger of refilling the bottles at home. The only downside is that the heater is no longer as portable, since the 20 pound bottle of propane needs to be lugged around. You can also buy the heater along with the hose, which is what I did.

The better method, it seems to me, is to use the relatively inexpensive hose shown available from Mr. Heater. This is designed to be used with the Mr. Heater, and lets you run it directly from the larger 20 pound bottle. You no longer have to worry about the inconvenience and slight danger of refilling the bottles at home. The only downside is that the heater is no longer as portable, since the 20 pound bottle of propane needs to be lugged around. You can also buy the heater along with the hose, which is what I did.

Now that we have the Mr. Heater Buddy, I feel more secure about winter power outages. While they would still be an inconvenience, it would no longer be life threatening. If such an event appeared likely, I would purchase one or more extra 20 pound bottles of propane, which are available at two stores within walking distance of my house. They could be sold out, but if I act fast, I can probably secure one. And even if I don’t, I always have at least one, which will provide heat for 2-4 days.

I have both the adapter hose to run the heater from the large container, and also have the refill adapter to re-use any small cans we have. (And we usually have at least a couple of those on hand.)

In anticipation of a power outage, I would set the heat higher than usual, and prepare to seal off unused rooms. If the power went out, I would seal them off, and also set the faucets to dripping. At that point, I would fire up the propane heater and move it as needed to the four rooms where the heat is needed.

I won’t know for sure until it happens, but I’m confident that this strategy will keep my family relatively comfortable, as well as preventing any damage to plumbing due to freezing.

Indoor Kerosene Heaters

Indoor Kerosene Heaters

Another option, with which I am less familiar, is a kerosene heater, such as the this one. Kerosene heaters seem to be more expensive than their propane brethren, but they could also be a good solution. For most people, the liquid kerosene fuel is easy to store. In my experience, it’s not for sale as many places as propane, but if you stock up before the emergency, this might be a good option.

Safety First

Whatever fuel you choose, keep in mind that you need to buy a heater that is safe for indoor use. Some of them are, but most are not. All of the heaters shown on this page are designed for indoor use, and are safe to be used in the house. (The ones designed for indoor use have an important safety feature missing in outdoor heaters. They contain an oxygen depletion sensor which will shut them down automatically if the oxygen level gets too law. For this reason, however, the indoor units will not work at high altitudes.)

Whatever fuel you choose, keep in mind that you need to buy a heater that is safe for indoor use. Some of them are, but most are not. All of the heaters shown on this page are designed for indoor use, and are safe to be used in the house. (The ones designed for indoor use have an important safety feature missing in outdoor heaters. They contain an oxygen depletion sensor which will shut them down automatically if the oxygen level gets too law. For this reason, however, the indoor units will not work at high altitudes.)

And having a battery-powered carbon monoxide detector is always important, but it takes on special importance when using new appliances to heat your home. It’s cheap insurance.

Note: Some of the links on this page are affiliate links, meaning that this website earns a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking the link.

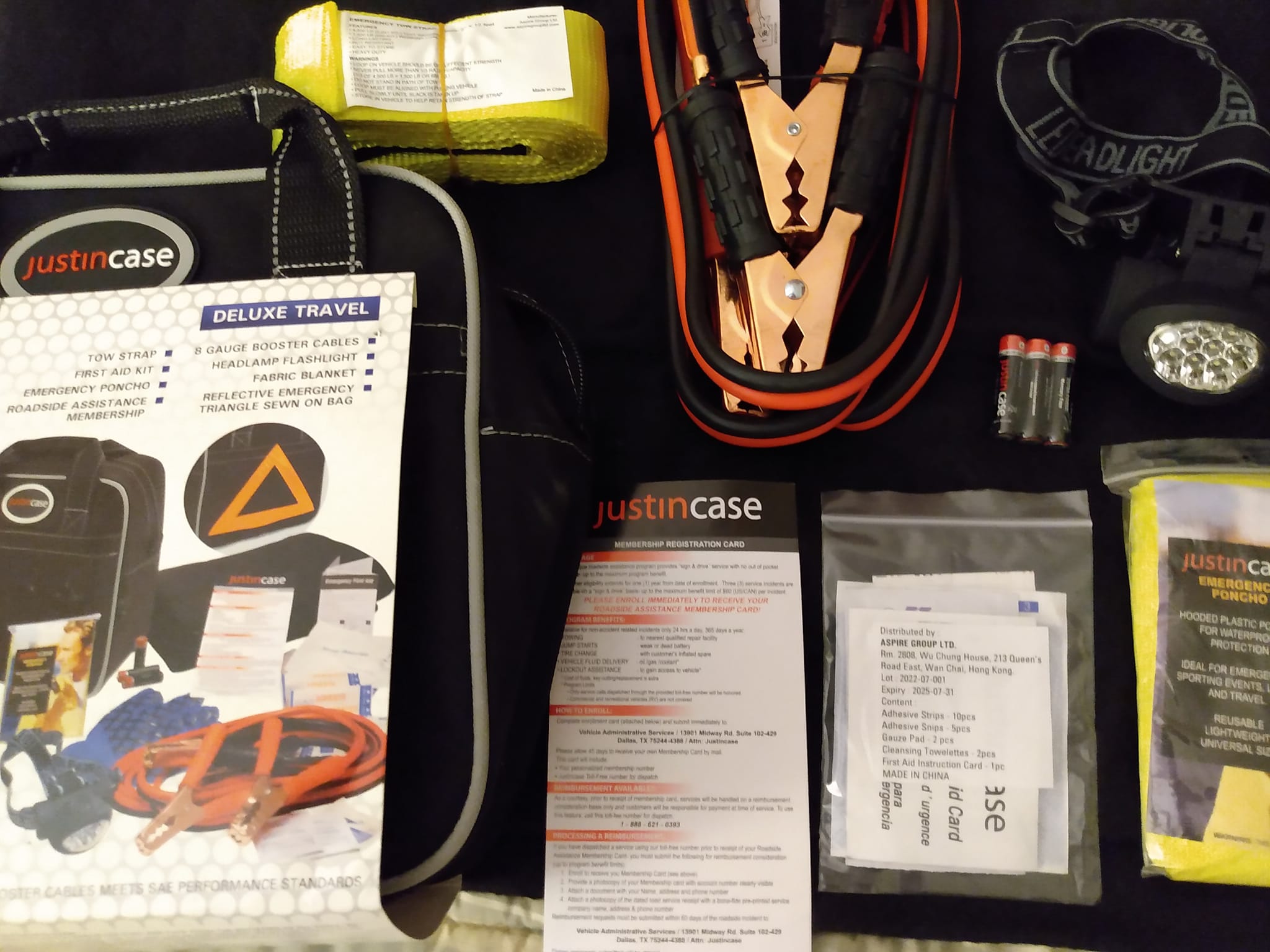

Bottom Line: Better than Nothing, The Price is Right, and Free Roadside Assistance.

Bottom Line: Better than Nothing, The Price is Right, and Free Roadside Assistance.If you’re looking for a rudimentary set of emergency gear to toss in your car, this one is by no means the deluxe version. But the price is right (click this link to see it on Amazon), and it’s all certainly better than nothing. It won’t take care of all of your emergency needs, but it might help if you’re in a tough situation and nothing else is available. Santa Claus brought me one, and I’m honoring him by putting it in my car.

Possibly the best value, though, is an automatic membership in a roadside assistance plan, named, like the product itself, Justincase. It purports to be a AAA-style assistance plan. After sending in the card that came with the kit, you can call a toll-free number, and they’ll come out and provide roadside assistance at no cost. A card is included, which you are directed to send in care of Vehicle Administrative Services of Dallas, TX. If you want to read the fine print of the details of the plan, click the image at left for a full-size image.

Possibly the best value, though, is an automatic membership in a roadside assistance plan, named, like the product itself, Justincase. It purports to be a AAA-style assistance plan. After sending in the card that came with the kit, you can call a toll-free number, and they’ll come out and provide roadside assistance at no cost. A card is included, which you are directed to send in care of Vehicle Administrative Services of Dallas, TX. If you want to read the fine print of the details of the plan, click the image at left for a full-size image.

about his experiences living in Kyiv, Ukraine, in the middle of a war. Wlad, like me, is an attorney, and lived a middle-class existence similar to mine, until Russia invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014. He and his family then relocated to Kyiv, but with Russia’s 2022 invasion, he was once again in the middle of the war. His wife and teen son and daughter evacuated to Poland, where they were able to find an apartment, thanks in part to the generosity of friends in America and elsewhere.

about his experiences living in Kyiv, Ukraine, in the middle of a war. Wlad, like me, is an attorney, and lived a middle-class existence similar to mine, until Russia invaded eastern Ukraine in 2014. He and his family then relocated to Kyiv, but with Russia’s 2022 invasion, he was once again in the middle of the war. His wife and teen son and daughter evacuated to Poland, where they were able to find an apartment, thanks in part to the generosity of friends in America and elsewhere.