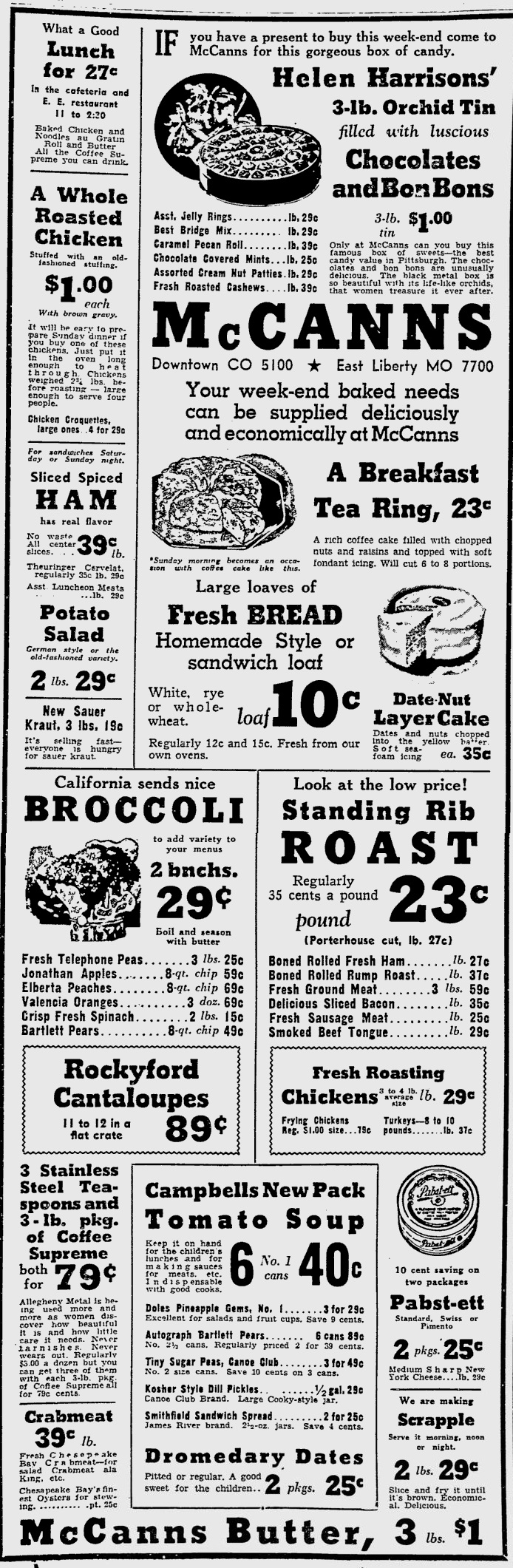

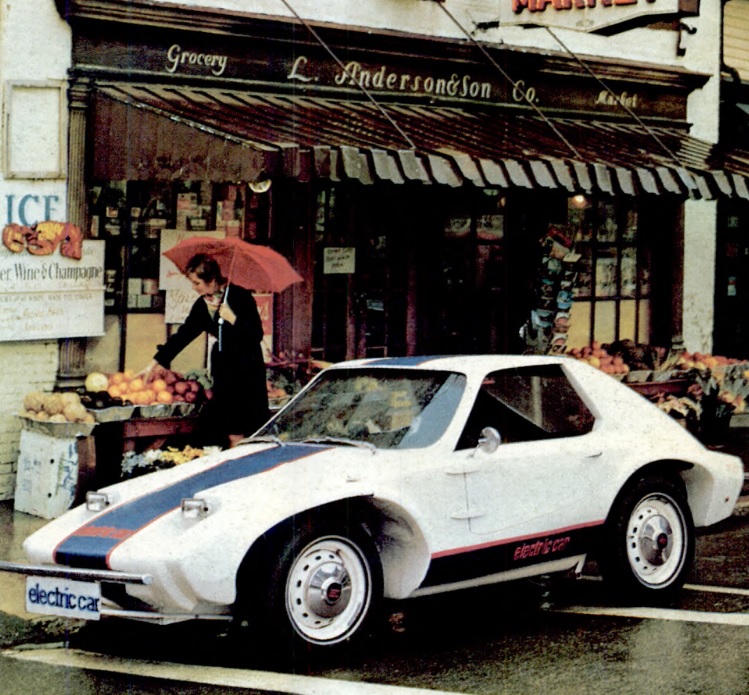

Electric cars are nothing new, as shown by this one on the cover of Popular Mechanics fifty years ago, September 1972. (In fact, we previously showed you one from 1909.)

Electric cars are nothing new, as shown by this one on the cover of Popular Mechanics fifty years ago, September 1972. (In fact, we previously showed you one from 1909.)

Electric motors have been extremely reliable for a long time, and they can develop high torque, even at zero RPM (which, incidentally, is why railroads now use them exclusively for moving trains). In addition, an electric motor will essentially last forever with little maintenance. And with the drive wheels driven directly by an electric motor, there’s no need for a transmission. (I still scratch my head and wonder why Toyota designed the Prius with a transmission, since it seems to me it would have been a lot easier and cheaper to drive the wheels directly, and use the gasoline engine solely for charging the battery.)

For over a hundred years, the limiting factor on electric vehicles has been the battery. All of the other parts are extraordinarily simple. It’s best to think of an electric car as being a battery, along with a few other parts, such as wheels, that make it move. So yes, when the battery dies, it probably means that the car is totaled. With internal combustion engines, the fuel tank lasts forever. But when the engine throws a rod after a few hundred thousand miles, then the car probably needs replacement. This is considered normal.

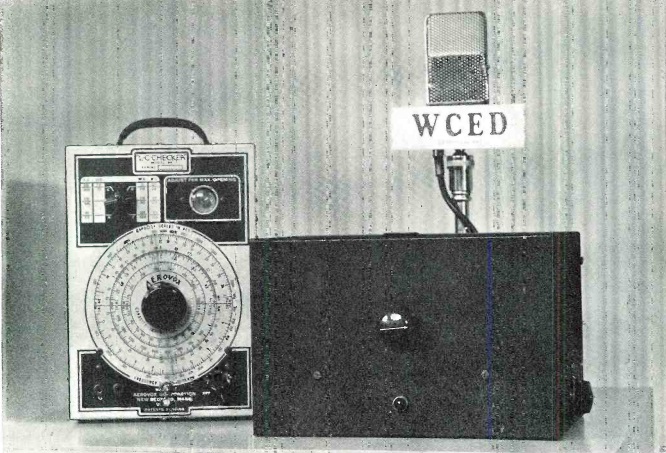

In 1972, however, this wasn’t quite the case. However, the battery had serious limitations. The car shown here is the Transit IV from Anderson Power Products of Bedford, Mass. (Yes, that appears to be the same company that makes Anderson Powerpole connectors, which have a nearly religious following.) The company was in talks with Avis to provide the vehicles for rental. The car had a range of 60 miles, making it useful for urban applications, although the magazine noted that it was not yet a replacement for vehicles to be driven on the road. It used twelve 12 volt lead-acid batteries, which could be charged in the vehicle, or removed. The recharging time was said to be 4-5 hours.

The $300 battery pack was said to be good for about 400 discharge cycles, or about 20,000 miles, which works out to a cost of about one cent per mile, plus, of course, the cost of the electricity. Since they were just garden variety lead-acide batteries, they were designed for replacement.

At the time, the magazine predicted that molten salt batteries would be the next development that would make electric vehicles practical for more application. It was actually the lithium-ion battery that was the breakthrough to make electric cars (and many other portable devices) practical or close to practical for most applications.

The editors did a road test of the vehicle. The first observation was that when the ignition is turned on, all is quiet, and only a small red light indicated that it was ready to go. The car reached its 65 MPH top speed in eerie silence, the only sounds being the whirr of the 20 HP DC motor and the hiss of the tires on the road. The editors concluded that “as an urban car it sure makes a lot of sense.”

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after following the link.

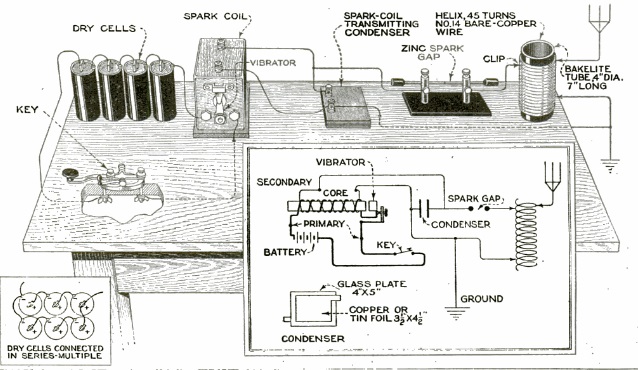

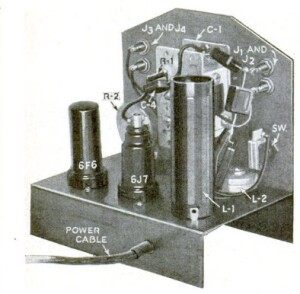

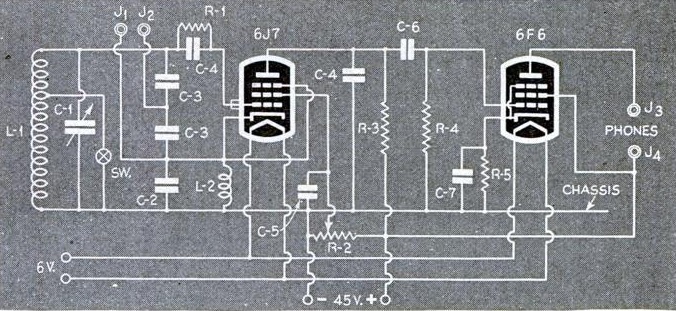

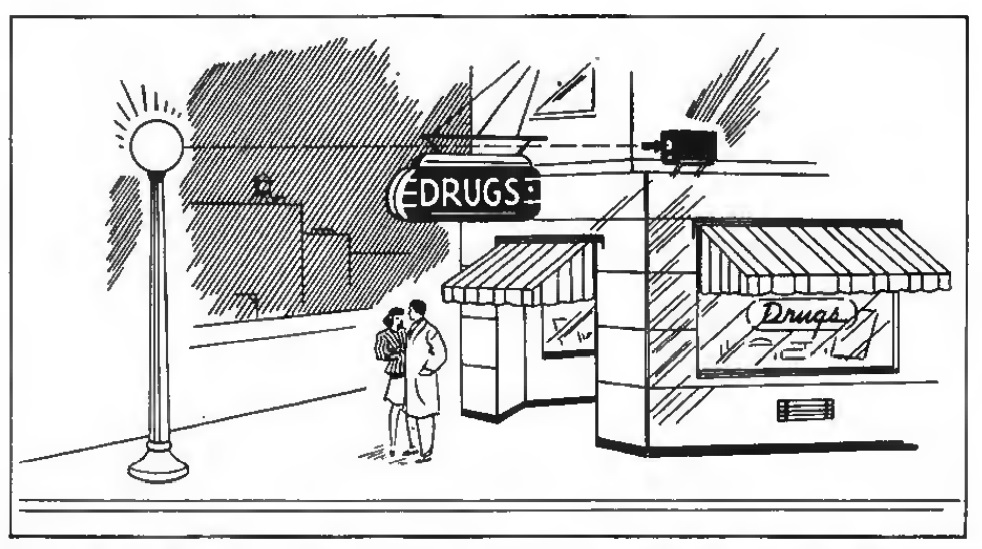

With civilian radio production suspended for the duration in 1942, many radio dealers were in search of additional lines of business to fill the gap. The September 1942 issue of Radio Retailing offered a number of suggestions involving applications of photocells. Above, with the possibility of wartime blackouts, a business owner would need a way to shut off his electric sign quickly in case the order was given. One way to do it automatically would be to wire the sign to a photocell pointed at the closest streetlight. When the town shut off the streetlights, his sign would immediately go dark.

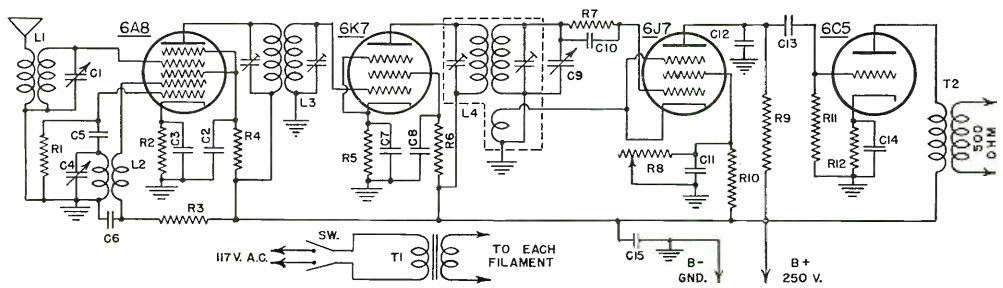

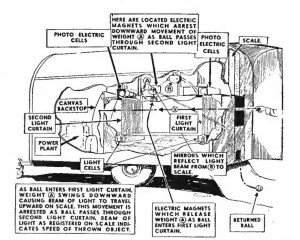

With civilian radio production suspended for the duration in 1942, many radio dealers were in search of additional lines of business to fill the gap. The September 1942 issue of Radio Retailing offered a number of suggestions involving applications of photocells. Above, with the possibility of wartime blackouts, a business owner would need a way to shut off his electric sign quickly in case the order was given. One way to do it automatically would be to wire the sign to a photocell pointed at the closest streetlight. When the town shut off the streetlights, his sign would immediately go dark. Various industrial applications were suggested, as well as, of course, use of electric eyes in security systems. Shown at right was a design used the by Cleveland Plain Dealer, to measure the pitching speeds of various pitchers. A trailer was equipped with the system shown here, and the player was to pitch into an opening in the back of the trailer. The ball would pass through two beams of light, and from the difference in time, the speed would be measured.

Various industrial applications were suggested, as well as, of course, use of electric eyes in security systems. Shown at right was a design used the by Cleveland Plain Dealer, to measure the pitching speeds of various pitchers. A trailer was equipped with the system shown here, and the player was to pitch into an opening in the back of the trailer. The ball would pass through two beams of light, and from the difference in time, the speed would be measured.Of course, today, the aspiring major league pitcher can get the same thing surprisingly inexpensively. The device shown here uses radar to measure the ball’s speed and does not require an entire trailer to move around.