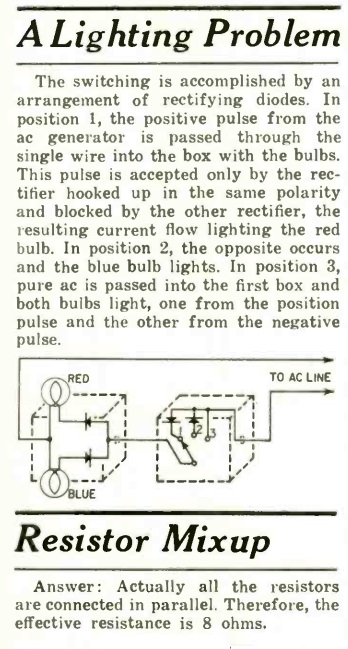

As promised, here are the answers to yesterday’s quiz. They appeared in the September 1961 issue of Radio-Electroincs.

As promised, here are the answers to yesterday’s quiz. They appeared in the September 1961 issue of Radio-Electroincs.

As promised, here are the answers to yesterday’s quiz. They appeared in the September 1961 issue of Radio-Electroincs.

As promised, here are the answers to yesterday’s quiz. They appeared in the September 1961 issue of Radio-Electroincs.

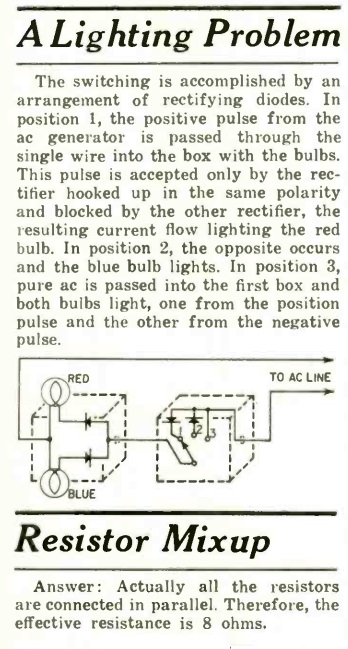

These two quizzes appeared 60 years ago in the August 1961 issue of Radio Electronics.

These two quizzes appeared 60 years ago in the August 1961 issue of Radio Electronics.

We’re confident that most of our readers can figure them out. If not, we’ll post the answers tomorrow. If these look vaguely familiar, it’s probably because you’ve seen them here before. The first “black box” quiz is very similar to a circuit we showed previously from October 1956 QST. And the second one with resistors is almost identical (only the values have changed) to the one we previously showed from the January 1957 issue of QST.

The 1961 answers (which are similar to the 1956-57 answers) will appear here tomorrow.

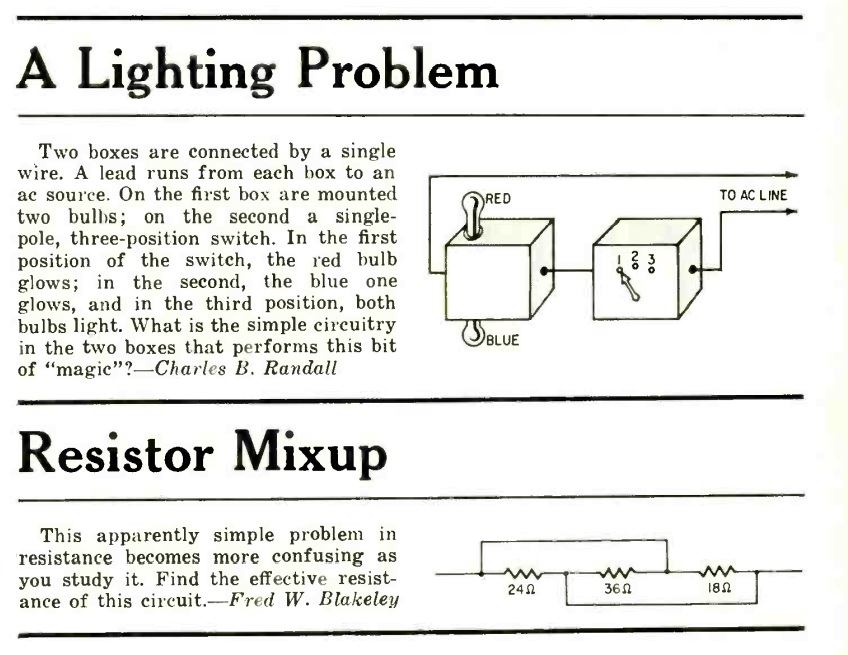

FM stereo is 60 years old this year, and 60 years ago this month, the August 1961 issue of Radio Electronics carried an update on the status of FM stereo broadcasting. The format had been approved by the FCC on April 19, 1961, and the first station to start stereophonic broadcasting was GE-owned WGFM in Schenectady, NY, followed soon by Zenith’s WEFM in Chicago.

FM stereo is 60 years old this year, and 60 years ago this month, the August 1961 issue of Radio Electronics carried an update on the status of FM stereo broadcasting. The format had been approved by the FCC on April 19, 1961, and the first station to start stereophonic broadcasting was GE-owned WGFM in Schenectady, NY, followed soon by Zenith’s WEFM in Chicago.

FM stations were free to start stereo service whenever they wanted, as long as they used approved equipment and gave the FCC 10 days’ notice. But the magazine noted that due to shortages of equipment, there would only be 20-25 stations on the air before the end of the year.

The magazine was advertising a few stereo receivers, and the article noted that there were two ways to get stereo. Some receivers had been constructed with multiplex inputs, and the manufacturers were tooling up to produce adapters. However, in most cases, it would be necessary to use an adapter from the same manufacturer.

Table model receivers were also soon available. The magazine predicted that FM stereo would not mean the end of monophonic FM. In fact, the additional demand for FM stereo would probably add interest to FM in general, to the benefit of stations broadcasting in mono.

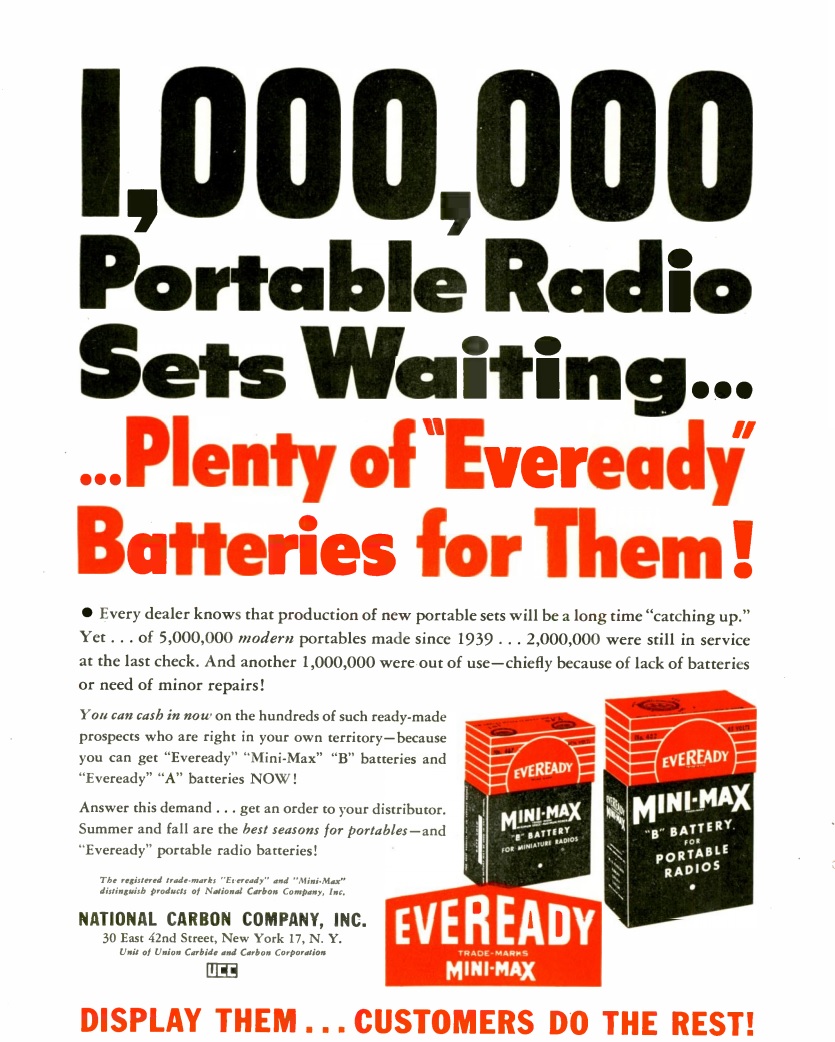

Seventy five years ago this month, the August 1946 issue of Radio Retailing carried this ad for Eveready batteries. The wartime years were ones of shortages of many consumer products, and radio batteries were difficult or impossible to find.

Seventy five years ago this month, the August 1946 issue of Radio Retailing carried this ad for Eveready batteries. The wartime years were ones of shortages of many consumer products, and radio batteries were difficult or impossible to find.

Millions of portable radios had been manufactured since 1939, but a million of them were out of service, mostly because no batteries were available. Summer was prime time for portables, and Eveready reminded dealers that if they put the batteries on display, they would sell themselves.

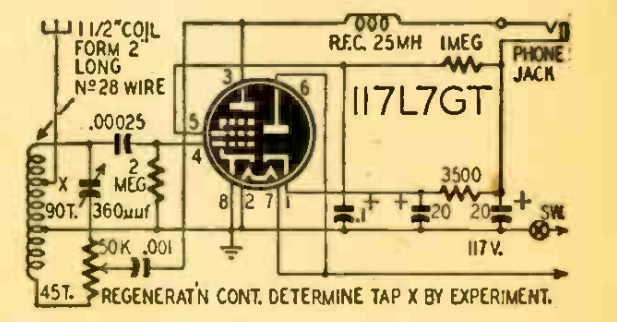

Seventy-five years ago this month, the August 1946 issue of Radio Craft carried this simple circuit for a one-tube receiver. The circuit had been sent in to the magazine by one Robert Sherrington of High Prairie, Alberta, who noted that the circuit was very selective and would pull in locals with good volume on a loudspeaker. It employed a 117L7GT, half of which served as a rectifier, with the other half serving as a regenerative detector.

Seventy-five years ago this month, the August 1946 issue of Radio Craft carried this simple circuit for a one-tube receiver. The circuit had been sent in to the magazine by one Robert Sherrington of High Prairie, Alberta, who noted that the circuit was very selective and would pull in locals with good volume on a loudspeaker. It employed a 117L7GT, half of which served as a rectifier, with the other half serving as a regenerative detector.

The designer of the circuit was almost certainly the same Robert Sherrington, who was 16 at the time he sent the circuit into the magazine. According to his 2015 obituary, he attended the Radio College of Canada in Toronto in 1949, and then owned a radio repair shop in High Prairie. He later moved to British Columbia, where was licensed as VE7DLX.

The magazine’s editor noted that the circuit, while unusual for the time, was not new, having been used in earlier receivers, including the Reinartz.

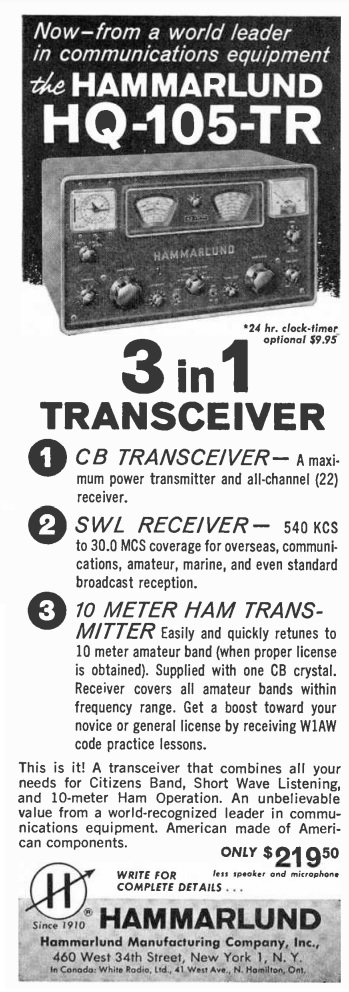

Sixty years ago this month, the August 1961 issue of Popular Electronics included this ad for an unusual combination from Hammarlund–the model HQ-105-TR.

Sixty years ago this month, the August 1961 issue of Popular Electronics included this ad for an unusual combination from Hammarlund–the model HQ-105-TR.

The set was basically an HQ-100 receiver with one added feature: It included one additional tube for the CB transmitter. One CB crystal was included, and the receiver’s audio amplifier was used as the modulator.

The receiver covered the broadcast band up to 30 MHz, and had a bandspread calibrated for the ham bands. The ad noted that when the owner got the general class ham license, the transmitter could be easily retuned to the 10 meter band. In the meantime, the receiver could be used to copy W1AW code practice toward getting that license.

You can view the receiver in action in this video:

Interestingly, the mike connection is in the back, and there is no indication on the front panel that the unit also contains a transmitter.

Seventy years ago this month, the August 1951 issue of Radio Television Retailing reminded dealers that there was money to be made by selling clock radios, an item that readily sold to people in all income brackets.

Seventy years ago this month, the August 1951 issue of Radio Television Retailing reminded dealers that there was money to be made by selling clock radios, an item that readily sold to people in all income brackets.

The clock radio “looks just like any other table model set” to the customer, so some salesmanship was required. The salesman needed to be thoroughly familiar with the product, and emphasize the low price for something that could serve as a fine radio, an alarm clock, a timekeeper, and in many cases, an automatic outlet.

The magazine suggested that direct mail might be a profitable way to sell. Select customers could be sent a mailing offering a set on approval, and once in the home, the customer was very likely to keep the set.

Seventy five years ago today, the August 12, 1946 issue of Life magazine carried this ad for the RCA model 56X and some variations. The set is a six-tube superhet covering the broadcast band, and retailed for $25.40 in its walnut plastic cabinet. The same radio with the creamy ivory finish, model 56X2 sold for $27.50, and the 56X3 in a wooden cabinet had a list price of $33.95.

Seventy five years ago today, the August 12, 1946 issue of Life magazine carried this ad for the RCA model 56X and some variations. The set is a six-tube superhet covering the broadcast band, and retailed for $25.40 in its walnut plastic cabinet. The same radio with the creamy ivory finish, model 56X2 sold for $27.50, and the 56X3 in a wooden cabinet had a list price of $33.95.

We’ve previously featured the 56X5, which added one shortwave band and earned the set the “12,000 Miler” moniker. The shortwave set sold for $37.95.

For an idea of how much groceries cost during the Depression, this ad appeared 85 years ago today in the August 11, 1936, issue of the Pittsburgh Press.

For an idea of how much groceries cost during the Depression, this ad appeared 85 years ago today in the August 11, 1936, issue of the Pittsburgh Press.

The prices look like bargains, but for many, cash was scarce, and there’s been a lot of inflation since then. According to this inflation calculator, a dollar in 1936 is the equivalent of $19.55 today. So a pound of coffee or a pound of wieners sounds like a bargain for a quarter, but that’s almost $5 per pound in today’s money.

The ham patties sound good, and I’d probably be convinced to hand over a silver quarter and a silver dime to get a pound. And they were appropriate for breakfast, luncheon, or dinner, so you can’t really go wrong. But if that was too expensive, the fresh sea trout was only a dime a pound. As with anything, it “would be priced higher if it were not as plentiful as it is.”

If Junior just announced that the science fair project is due tomorrow, but the project hasn’t even been started, there’s no need to panic. Thanks to these simple projects from 85 years ago, it’s still possible to get an A on the assignment, and the teacher will assume that many weeks of planning went into the project.

If Junior just announced that the science fair project is due tomorrow, but the project hasn’t even been started, there’s no need to panic. Thanks to these simple projects from 85 years ago, it’s still possible to get an A on the assignment, and the teacher will assume that many weeks of planning went into the project.

Shown above is a simple method of determining the center of gravity (or, since the teacher will prefer the more scientifically accurate term, the center of mass) of an object. Cardboard is used, but any similar substance of uniform thickness will work fine. After the pattern is cut out, the design is hung by one edge. A plum line (which is just a piece of string, with a weight on one end) is hung from the same point, and it is traced on the item. Then, it’s hung from another edge. Where the two lines intersect, that is the center of mass.

The other project, shown below, gives a visual indication of sound waves. All that’s needed is a couple of cardboard tubes, a balloon, and some sand. Both projects appeared in the August 1936 issue of Popular Science.