Sixty years ago, the U.S. Post Office tried something that Popular Electronics, in its April 1961 issue, called “Electronic Speed Mail.” The official name for the service was just “Speed Mail,” but it was an early hybrid of electronic mail (or more accurately, facsimile) and snail mail.

Sixty years ago, the U.S. Post Office tried something that Popular Electronics, in its April 1961 issue, called “Electronic Speed Mail.” The official name for the service was just “Speed Mail,” but it was an early hybrid of electronic mail (or more accurately, facsimile) and snail mail.

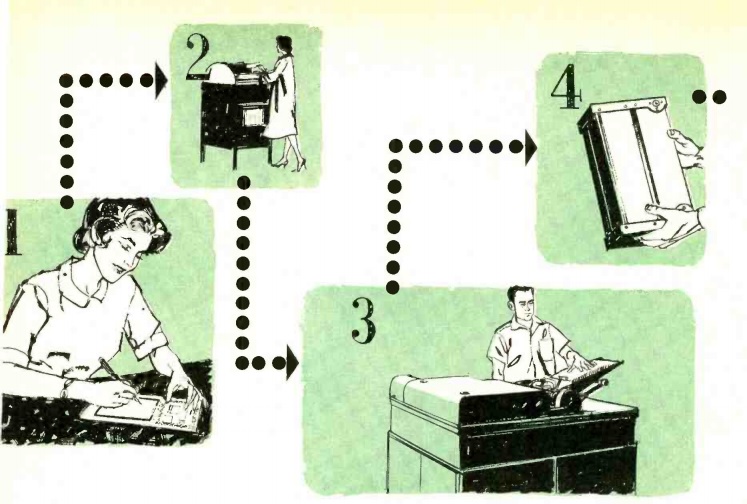

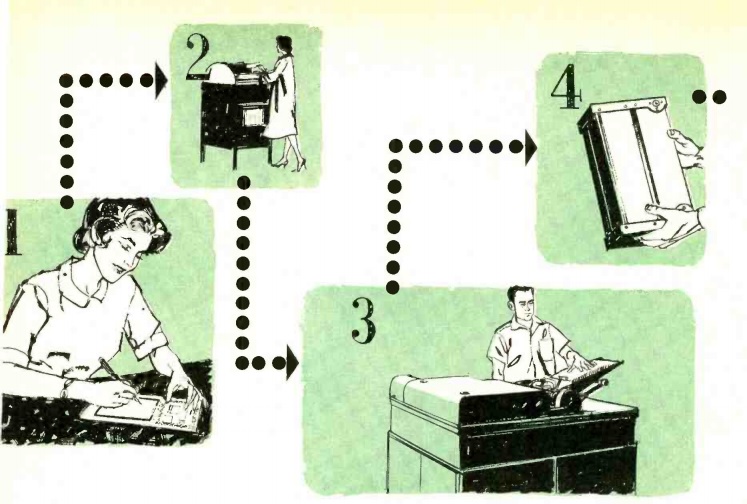

The Post Office Department envisioned having centers in 71 cities strategically located across the country. To write a letter that would be delivered the same day, a sender would write the letter on a special form provided by the post office, taking care to write only within the lines. The form was likened to the special “V-Mail” form of World War II, with which letters were microfilmed stateside and delivered to Army Post Offices where they were printed and delivered, or vice versa. In this case, the message form was sealed and deposited into the mails. At the local post office, it was fed in, still sealed, to a facsimile machine. The machine opened the mail, scanned it, and placed it into a sealed container. After the operator was sure that the message had been properly sent, the batch of message forms was destroyed.

The scanned message was then sent via the Echo 1 satellite to the closest post office to the recipient. There, the message was printed and sealed into a window envelope with only the recipient’s address and return address showing. Again, the entire process took place without human eyes seeing the message.

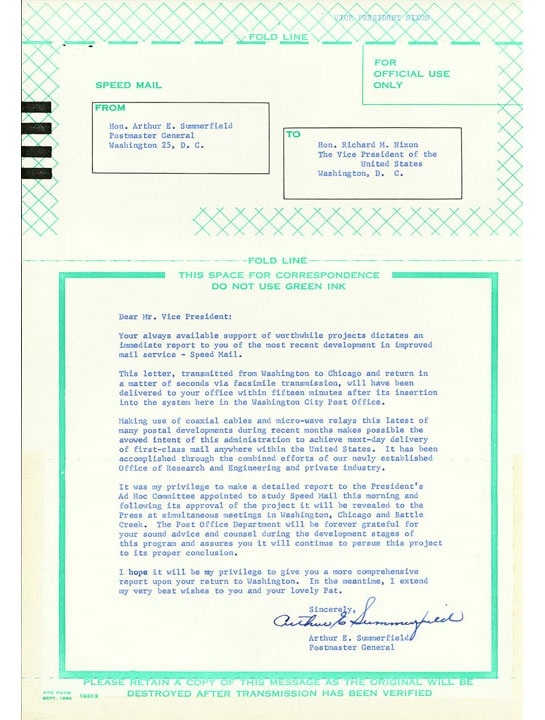

An example of the message blank is shown below. This one bears a message sent from Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield to Vice President Nixon, late in 1960. (Even though the message was sent crosstown in Washington, it was relayed via Chicago to demonstrate the service’s capabilities.)

When the Kennedy Administration took office, newly appointed Postmaster General J. Edward Day (best known for the creation of the ZIP code) was less enamored with the system, and no further efforts were made to promote it. The Western Union Mailgram service (“the impact of a telegram at a fraction of the cost”) was introduced nine years later in 1970, and allowed rapid mail service. Messages were sent by Western Union to the nearest post office, where they were printed and delivered the same day received.

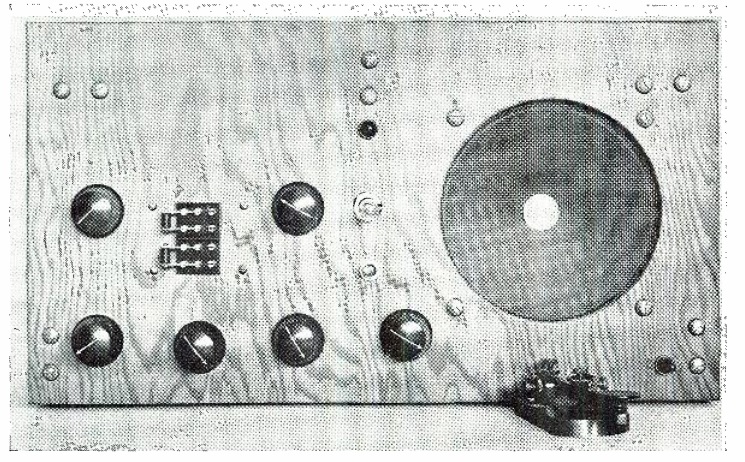

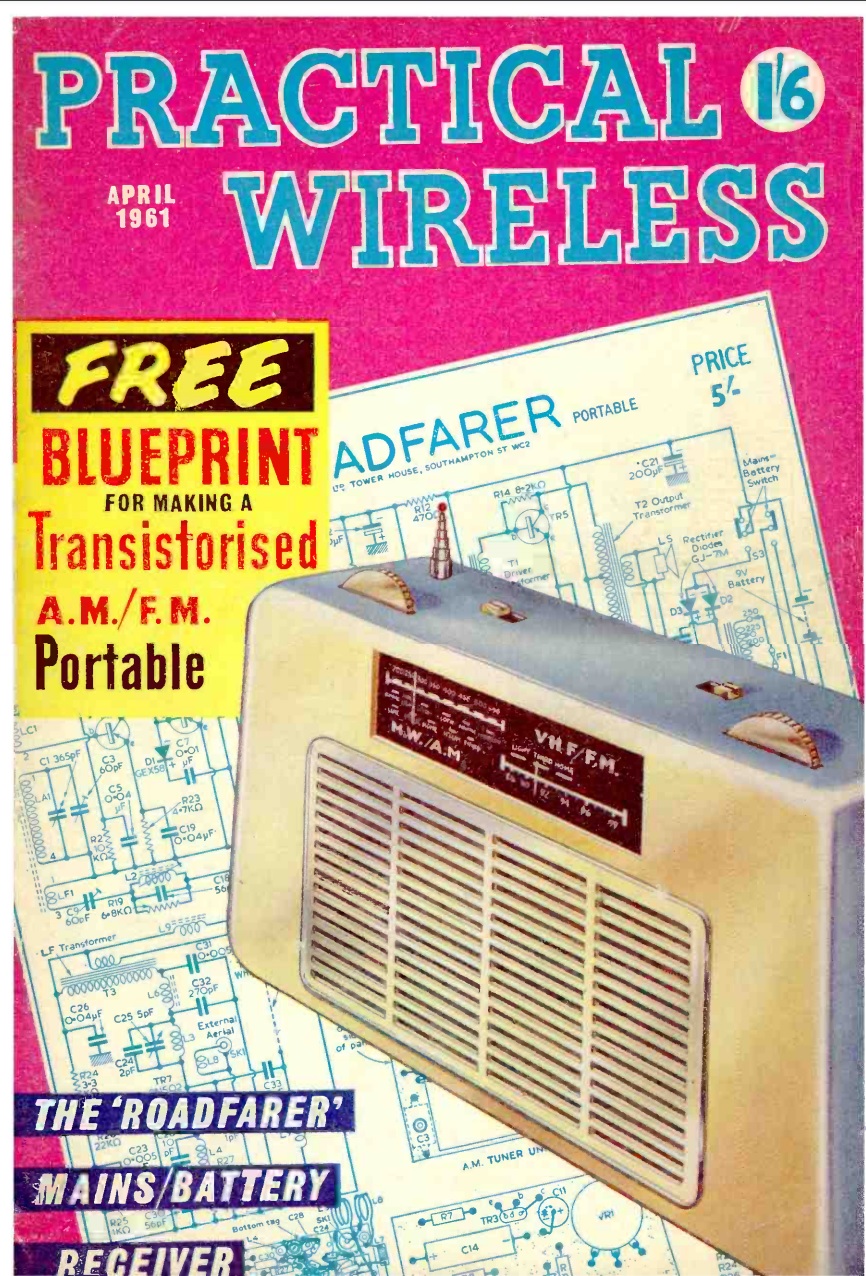

Sixty years ago, the April, May, and June 1961 issues of the British journal Practical Wireless contained the blueprints and construction details for this ambitious project, dubbed the “Roadfarer.” The set was a completely self-contained portable that would tune the longwave, mediumwave, and FM broadcast bands. It would operate on batteries, but also included an AC power supply to give greater economy when close to the mains.

Sixty years ago, the April, May, and June 1961 issues of the British journal Practical Wireless contained the blueprints and construction details for this ambitious project, dubbed the “Roadfarer.” The set was a completely self-contained portable that would tune the longwave, mediumwave, and FM broadcast bands. It would operate on batteries, but also included an AC power supply to give greater economy when close to the mains.