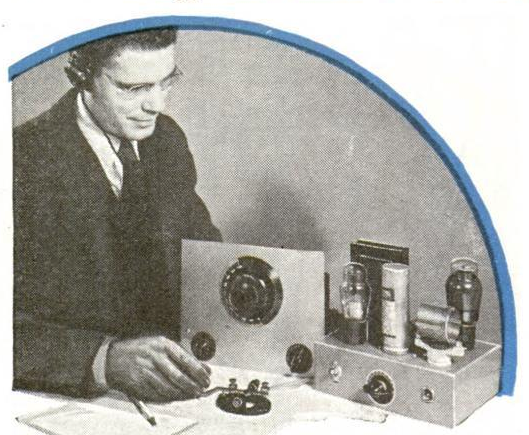

The September 1951 issue of Popular Mechanics showed how to put together this simple two-tube receiver. It was earmarked especially for the new ham, since it covered the 80 meter ham band. But it would also pull in a wider range of frequencies, including police calls and the 49 meter international broadcast band.

The September 1951 issue of Popular Mechanics showed how to put together this simple two-tube receiver. It was earmarked especially for the new ham, since it covered the 80 meter ham band. But it would also pull in a wider range of frequencies, including police calls and the 49 meter international broadcast band.

The timing of the article wasn’t a coincidence, since the circuit was specifically targeted at those interested in the Novice class amateur radio license. That new license, which required only a 5 word per minute code test, had just been announced by the FCC, which started issuing them on July 1, 1951. Armed with this receiver, and a key and buzzer, the prospective Novice would be able to pass the test with ease. The magazine promised that the October issue would include an accompanying transmitter.

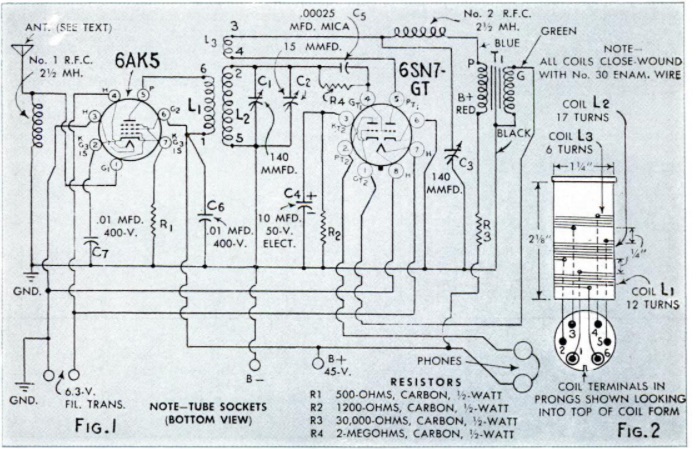

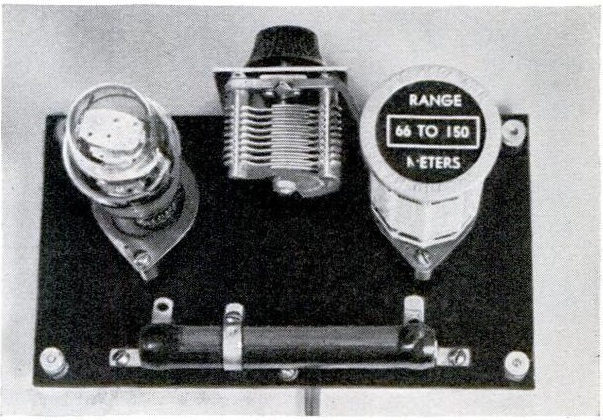

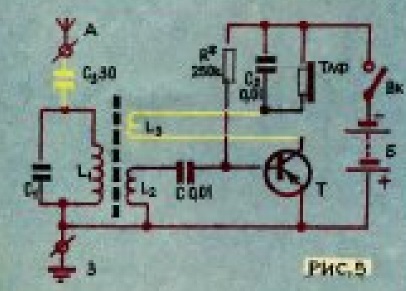

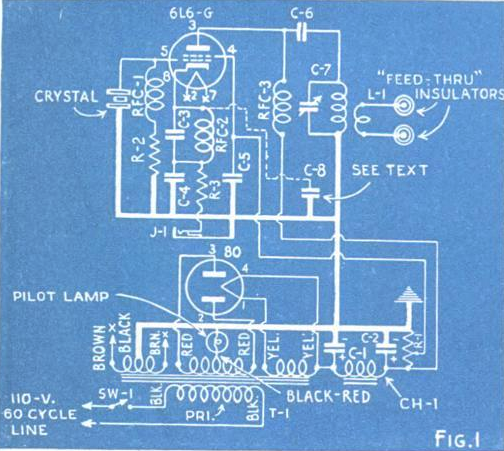

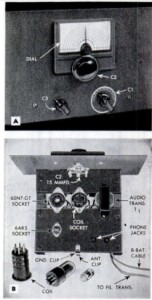

Construction was simple, as it used two pieces of hardwood mounted on wooden cleats. There was a gap between the two boards, allowing for easy mounting of the sockets for the two tubes and one plug-in coil. Power came from a 45 volt battery, but to prevent having to replace A batteries, a 6.3 volt transformer was used to light the filaments. No power switch was provided, and the magazine noted that a switch could be mounted somewhere on the operating table in line with the transformer.

The magazine recommended a 10-15 foot indoor antenna and ground for the two-tube regenerative set. One variable capacitor was used to control regeneration, with another one serving as the main tuning dial. The procedure for using the set was to advance the regeneration until the set came to life, and then tune the main tuning dial until 80 meter stations were heard. At that point, the larger bandspread dial would be used for tuning.