Bottom Line: The Opinel is a very inexpensive and unpretentious high quality knife for your everyday carry needs.

Pre-pandemic, I very rarely carried a pocket knife. When I needed a cutting tool, I looked around the garage or kitchen and found something suitable. In the car, I would find a cheap utility knife in the toolbox which would usually serve the purpose.

But with the pandemic, it seemed that I needed a knife multiple times per day. More often than not, it was to open a box from Amazon or Walmart. I like to do this outside, so that I can immediately discard the outer packaging into the recycling bin. Thus, it became convenient to keep a knife in my pocket. I had several around the house, many of which had been given to me as gifts over the years. The first one I stumbled upon was the Opinel No. 6 Stainless Steel folding knife.

As you can see from the picture, the Opinel is a nondescript knife with a wooden handle. It looks like a tool, which, of course, is exactly what it is. It doesn’t have a camouflage handle. It doesn’t have a built-in screwdriver or can opener. It’s benign looking, and designed for cutting things, a goal which it accomplishes remarkably well. It’s well made, and it seems to keep a cutting edge well. I’ve sharpened it a couple of times with a whetstone, and the edge seems to last.

My version came in stainless steel, and the knife is also available in carbon steel. Apparently, the carbon steel blade holds an edge a bit better, but is more prone to rust. The stainless steel (marked on the blade in French, Inox, short for inoxidable) seems the more practical choice.

The Number 6 in the product name indicates the length of the blade, the number 6 being 2.87 inches. The sizes range from a tiny Number 2, up to a Number 12 with a 4.84 inch blade. The number 6 seems to be the perfect size for the occasional jobs I use it for. In addition to opening boxes, I’ve used it to cut food while camping, strip wire, cut cords, and do the normal variety of tasks for which one would use a pocket knife. It’s big enough to do the jobs I need it for, but as it weighs only about an ounce, I hardly notice it in my pocket. The blade meets the “under three inches” standard which is important for some regulatory purposes. (On the other hand, at such time as it becomes safe to fly commercially, I’ll have to remember to leave it at home or in my checked baggage.)

The knife has a simple locking mechanism, which allows the blade to be locked open or closed. It’s simplicity itself–namely, a notched ring which can be twisted to hold the blade in place. In my opinion, most locking mechanisms are annoying and dangerous. If you’re using a knife in such a way that the blade might inadvertently close, then in my opinion, you are using it wrong. And most locking mechanisms I’ve seen require some contortion to disable them, such as holding down a button while moving the blade toward your finger. In most cases, in my opinion, the “safety” feature of a locking blade makes the knife less safe. In the case of the Opinel, however, the locking mechanism needn’t be used at all. In fact, I carried the knife around for quite some time before even realizing that the blade could be locked.

On the rare occasions when I might want to lock the blade on the Opinel, the mechanism and easy and safe to use. You merely rotate the ring to lock or unlock the blade.

Joseph Opinel began making knives in 1890 in Savoie, France, and the knife has always been the quintessential working man’s knife. Picasso reportedly used one as a sculpting tool. Today, about 15 million knives per year roll off the company’s assembly lines.

The Opinel knife is quite inexpensive, but high quality and useful. It’s unpretentious and looks like a tool, so it won’t draw the ire of those who are squeamish about knives. It’s the perfect knife to keep in your pocket. You’ll find you wind up using it several times per day.

Some links are affiliate links, meaning this site receives a small commission if you make a purchase after clicking on the link.

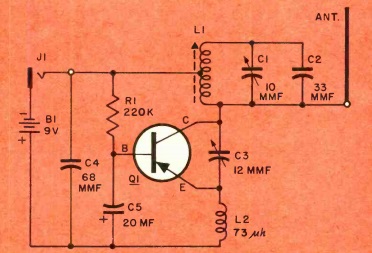

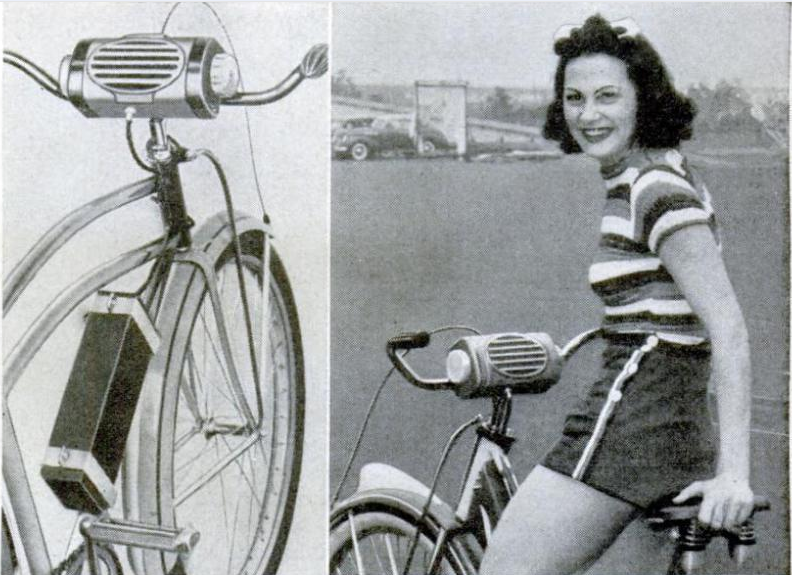

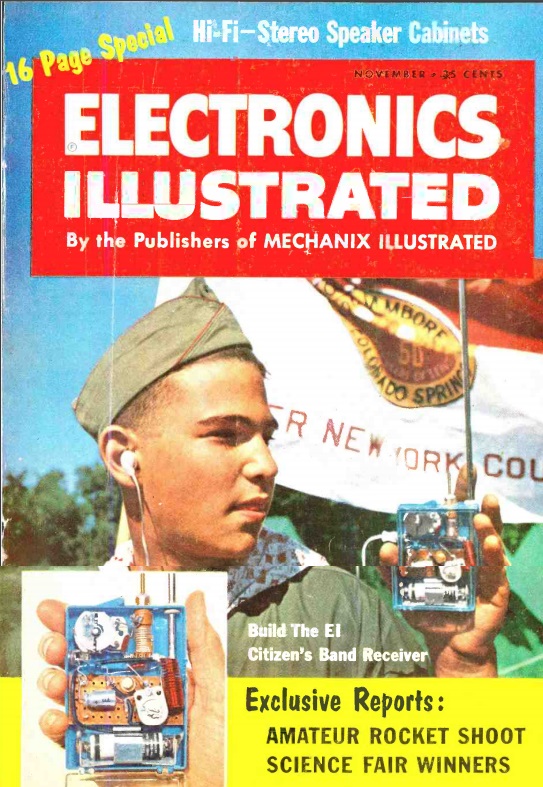

Sixty years ago, this New York scout made the front cover of the November 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated by demonstrating this one-transistor superregenerative receiver for the 11 meter Citizen’s Band.

Sixty years ago, this New York scout made the front cover of the November 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated by demonstrating this one-transistor superregenerative receiver for the 11 meter Citizen’s Band.