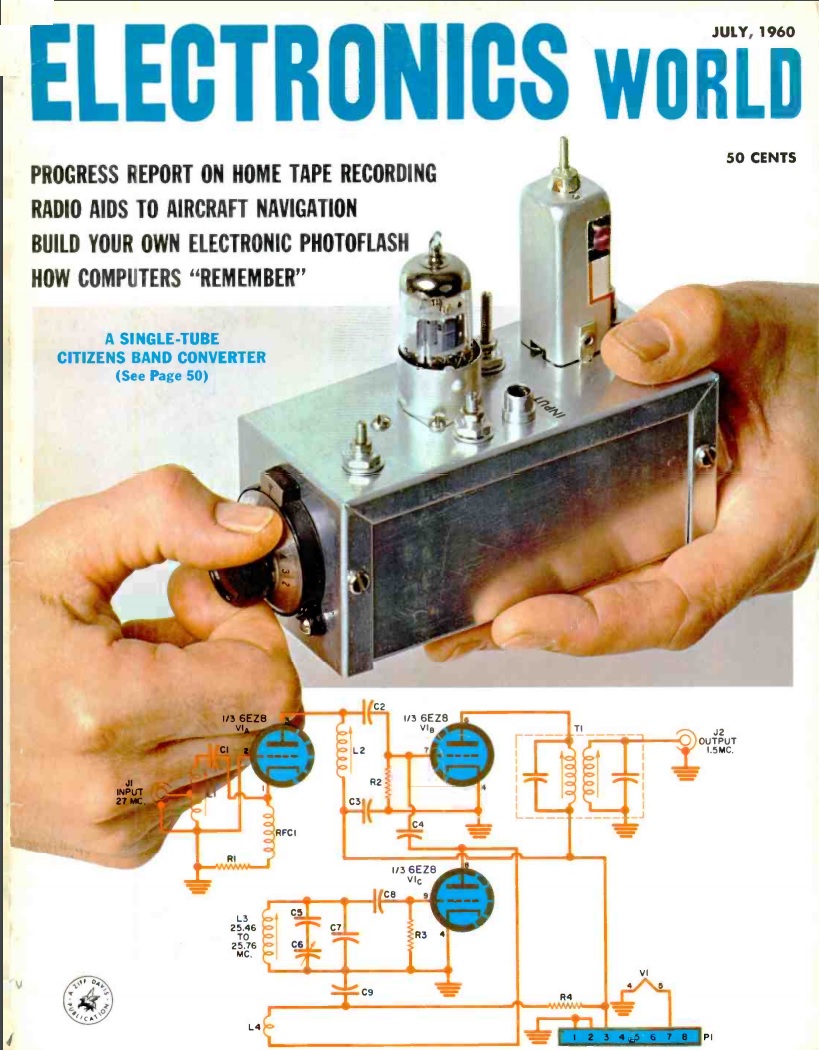

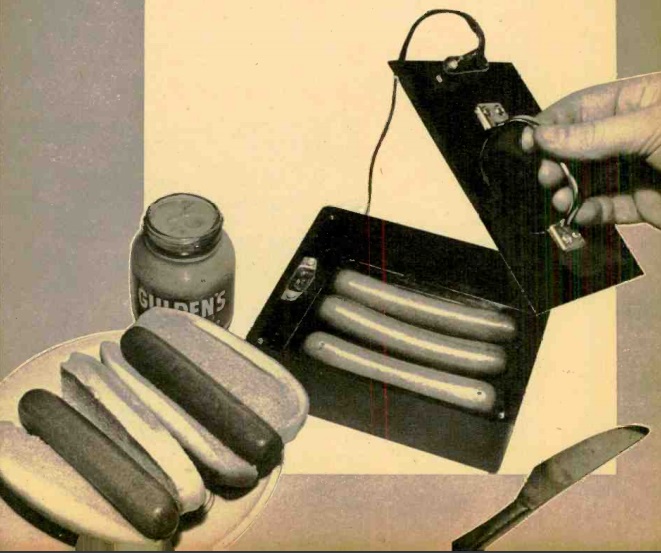

I suspect many of our readers have independently invented the idea shown here for an easy way to cook a hot dog. You simply run 120 volts through the hot dog, and the hot dog serves as a resistor and cooks itself. This incarnation of the idea was designed by prolific electronics writer Len Buckwalter and appeared in the July 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated.

I suspect many of our readers have independently invented the idea shown here for an easy way to cook a hot dog. You simply run 120 volts through the hot dog, and the hot dog serves as a resistor and cooks itself. This incarnation of the idea was designed by prolific electronics writer Len Buckwalter and appeared in the July 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated.

This design is a bit safer than what I remember doing. While cooking, the hot dogs are safely concealed inside a bakelite box. They don’t start cooking until the lid is inserted, since the cord is part of the lid, and there’s a TV-style safety interlock.

The young scientist wishing to come up with an interesting science fair project won’t go wrong with this idea. It give a great demonstration of Ohm’s law and the power law. And sharing the hot dogs with the judges certainly won’t hurt in earning that coveted blue ribbon.

Of course, you don’t want to be disqualified by electrocuting one of the judges, so it’s best to come up with some form of interlock.

The venerable Presto Hot Dogger used the same principle to cook hot dogs. It unfortunately seems to be out of production, but they show up on eBay. But making your own is easy, and a lot more fun.