Today is the 20th birthday of Bartholomew I of Constantinople, the Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church. He was born on February 29, 1940.

Today is the 20th birthday of Bartholomew I of Constantinople, the Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church. He was born on February 29, 1940.

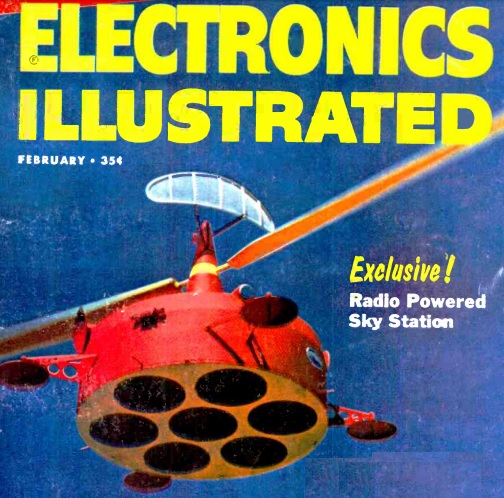

Sixty years ago this month, the February 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated the “radio powered sky station” shown here. It was an artist’s conception of the Raytheon Airborne Microwave Platform. It could be used for either civilian or military purposes, but would establish a platform 65,000 feet in the air. From there, it could relay radio or television signals, or serve as part of the nation’s missile defense system.

Sixty years ago this month, the February 1960 issue of Electronics Illustrated the “radio powered sky station” shown here. It was an artist’s conception of the Raytheon Airborne Microwave Platform. It could be used for either civilian or military purposes, but would establish a platform 65,000 feet in the air. From there, it could relay radio or television signals, or serve as part of the nation’s missile defense system.

The craft would be stationary above its power source, which consisted of a beam of microwave energy. This was picked up by an antenna on the bottom. It was rectified, and the resulting energy was used to power the propeller as well as the electronic payload.

I’ve never heard of this system being deployed, probably because the bugs never got worked out. This once classified 1965 military report (authored by Raytheon) speaks in glowing terms of the feasibility of the project (which presumably needed just a few more million dollars). However, as of 1965, successful experiments consisted of the successful use for ten continuous hours at 50 feet, a far cry from the 65,000 feet planned. And to keep the craft over the microwave beam, a tether was employed, which would probably be impractical at 65,000 feet.

It seems like an ambitious project for 1960, but it’s probably quite possible today. It seems to me that battery and solar technology will soon be at a point (if they’re not there already) where it’s possible to have a craft that will stay aloft indefinitely. And unlike the 1960 vision, it wouldn’t need to stay above a fixed point. If a craft can stay aloft indefinitely, this means that it can fly anywhere in the world.

It also seems to me that an autonomous military vehicle could derive its power from the enemy’s power grid. When it needed a charge, it could roost on a convenient power line. In fact, it could probably get its power inductively from an AC power line merely by flying close.

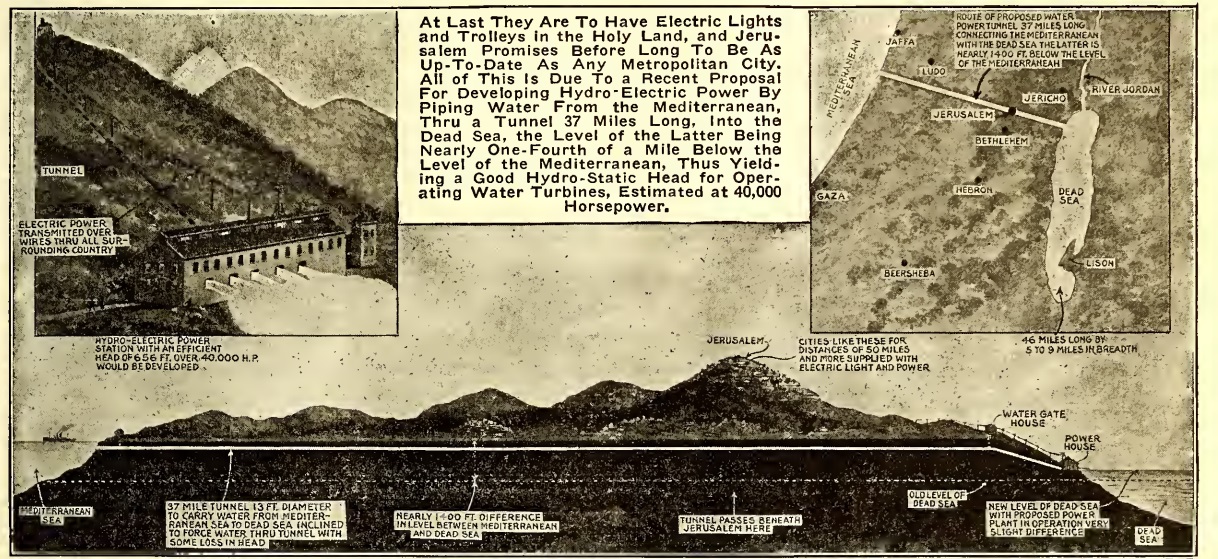

A hundred years ago this month, the February 1920 issue of Electrical Experimenter detailed this plan which surfaces from time to time: To get hydroelectric power by piping water from the Mediterranean Sea to the Dead Sea, which lies 1400 feet below sea level.

A hundred years ago this month, the February 1920 issue of Electrical Experimenter detailed this plan which surfaces from time to time: To get hydroelectric power by piping water from the Mediterranean Sea to the Dead Sea, which lies 1400 feet below sea level.

The necessary tunnel would be 37 miles long, and would pass about 2500 feet under Jerusalem. According to the magazine, the plan would bring electric lights and electric trolleys to the Holy Land.

More information about the various proposals for this project over the years can be found at Wikipedia.

This young woman, even if she weren’t armed with a giant magnifying glass, could easily change records without soiling her finger nails, thanks to the Vacuum Record Lifter, from Vacuum Record Lifter Ltd., 701 Seventh Avenue, New York.

This young woman, even if she weren’t armed with a giant magnifying glass, could easily change records without soiling her finger nails, thanks to the Vacuum Record Lifter, from Vacuum Record Lifter Ltd., 701 Seventh Avenue, New York.

The device appears to be a suction cup which is placed on the record. It had a vent hole at the top, which was covered by one finger. When the record is safely lifted, the vent can be opened, and the record falls gently into the other hand.

The device was invented by Joseph Menchen, whom the article calls the inventor of “the first liquid fire appliances used by the Allied armies.” Sure enough, Wikipedia lists Menchen as the inventor of a flame thrower, as well as “self-made businessman, film producer, screenwriter, and literary agent.”

The ad appeared a hundred years ago this month in the February 1920 issue of Talking Machine World.

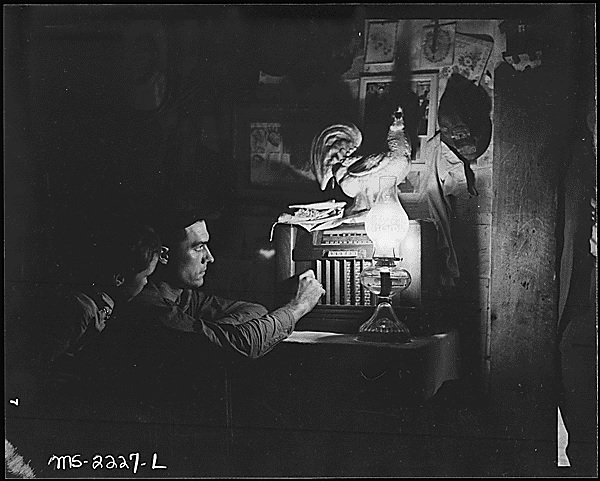

For this Kentucky coal miner in 1946, the radio was his link to the outside world. The photo is from the Department of the Interior, Solid Fuels Administration for War, and is dated September 4, 1946. It has the following caption:

For this Kentucky coal miner in 1946, the radio was his link to the outside world. The photo is from the Department of the Interior, Solid Fuels Administration for War, and is dated September 4, 1946. It has the following caption:

Charlie Lingar and his son listen to their battery radio. He has worked for the company for fourteen years but was injured in a mine explosion last December and hasn’t been able to work since then. His three room house for which he pays $6.75 monthly has no running water, no toilet, no electricity. Kentucky Straight Creek Coal Company, Belva Mine, abandoned after explosion [in] Dec. 1945, Four Mile, Bell County, Kentucky.

Lingar was more than injured in the explosion. He was trapped underground for over fifty hours after the explosion. He and eight other men barricaded themselves in, but left a note in the slate that they were there. The oldest of the men died, but the other eight, including Lingar, survived. According to some accounts, a mysterious lumberjack (or perhaps it was a telephone lineman) appeared out of a door leading to a well-lighted room and assured the men that they would be rescued. The man then returned to the well lit room, and closed the door.

I’m not able to identify the radio, but maybe some reader can. It’s a battery set, also often called a “farm set.” It seems to have two bands. If that’s the case, then it probably pulled in shortwave signals in addition to the standard broadcast band.

I’m not able to identify the radio, but maybe some reader can. It’s a battery set, also often called a “farm set.” It seems to have two bands. If that’s the case, then it probably pulled in shortwave signals in addition to the standard broadcast band.

The original photo is available at the National Archives, which has this description of the collection:

In 1946 the Department of Interior and the United Mine Workers agreed to a joint survey of medical, health and housing conditions in coal communities to be conducted by Navy personnel. Under the direction of Rear Admiral Joel T. Boone, survey teams went into mining areas to collect data and photographs on the conditions of these regions, later compiled into a published report. The bulk of the photographs were taken by Russell W. Lee, a professional photographer hired by the Department of Interior for this project; others were taken by the Navy. These photographs cover a complete range of activities in mining communities. They show the interior and exterior of both company-owned and priv dispensaries; miners at work performing various tasks; mining grounds, equipment and wash houses; women performing household functions; children at play; recreation facilities, churches, schools, clubs; scenes of mining townspeople in and around company stores and town streets; family portraits; members of the medical survey group inspecting grounds and speaking to mine company administrators, local mine operators and union officials.

Eighty years ago, the young man (or woman) with an interest in radio couldn’t go wrong with this one-tube kit from the 1940 Lafayette catalog. The set was a “baby in size but a giant in performance,” and pulled in the stations with a single type 30 tube. The kit went for $3.95, but also required the tube for 33 cents, an A battery for 33 cents, and a 22.5 volt B battery for 74 cents.

Eighty years ago, the young man (or woman) with an interest in radio couldn’t go wrong with this one-tube kit from the 1940 Lafayette catalog. The set was a “baby in size but a giant in performance,” and pulled in the stations with a single type 30 tube. The kit went for $3.95, but also required the tube for 33 cents, an A battery for 33 cents, and a 22.5 volt B battery for 74 cents.

Headphones were also required, which would set the builder back at least another 66 cents. The set came with a plug-in coil covering the broadcast band, but the young radio buff would almost certainly want to start pulling in the short waves. This was accomplished by ordering a set of four coils for only 74 cents.

The catalog noted that this was the type of set that most hams started with.

If I didn’t know any better, I would say that these Soviet diagrams from 50 years ago were suggestions for burglar alarms. Of course, they didn’t have to worry about burglars in the workers’ paradise, so they must have been something else. If I were able to read the text in the February 1970 issue of Юный техник, I would be able to come up with a more accurate description. But I’m guessing they’re probably designed to catch capitalist imperialist running dogs.

If I didn’t know any better, I would say that these Soviet diagrams from 50 years ago were suggestions for burglar alarms. Of course, they didn’t have to worry about burglars in the workers’ paradise, so they must have been something else. If I were able to read the text in the February 1970 issue of Юный техник, I would be able to come up with a more accurate description. But I’m guessing they’re probably designed to catch capitalist imperialist running dogs.

In any event, the two-transistor circuit at the left appears to be a solid-state relay to drive a buzzer. The other diagrams are self-explanatory, such as how to make a switch from a clothespin.

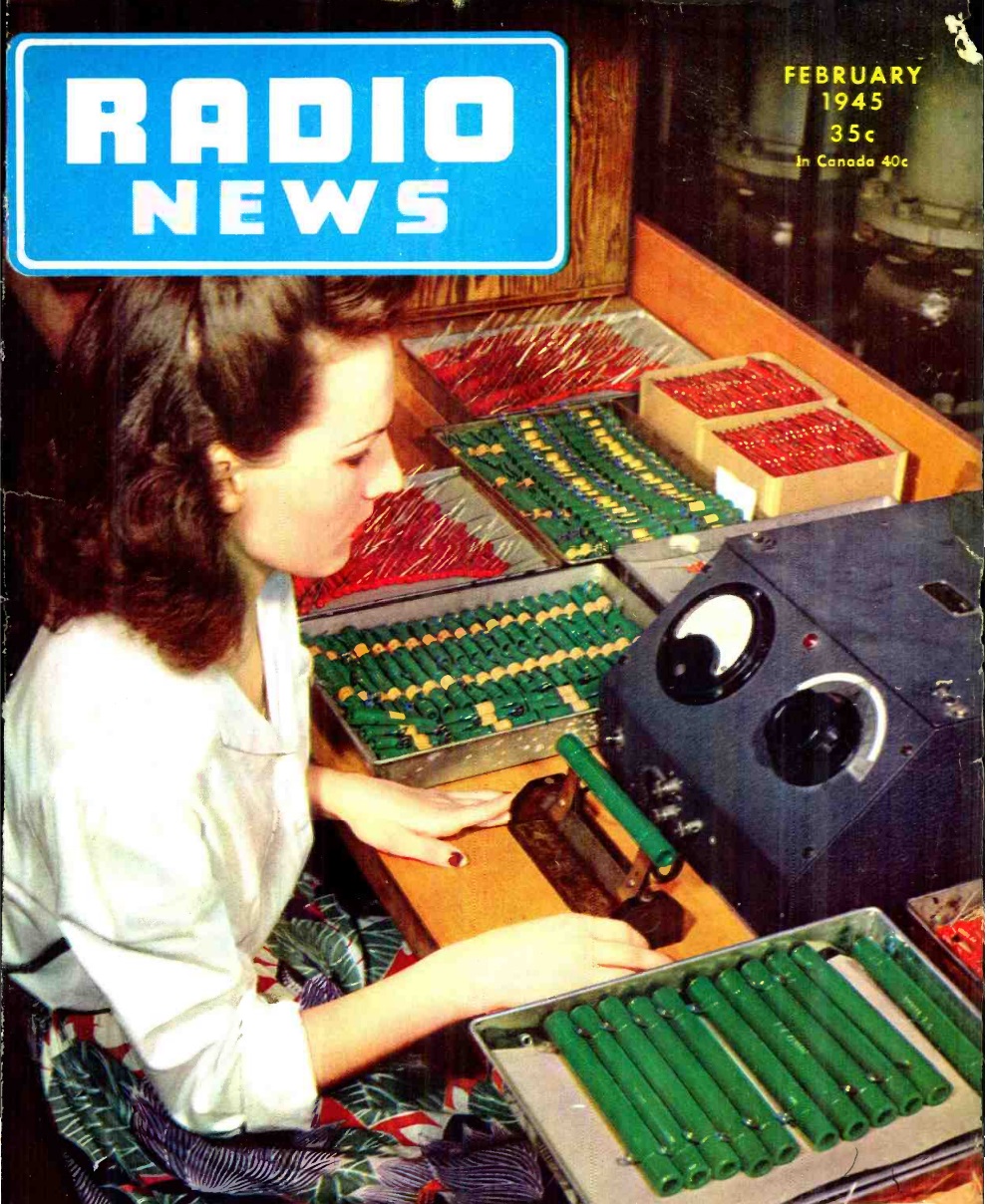

Seventy-five years ago, this Chicago war worker was testing RF chokes for their Q factor as they rolled off the assembly line of the Ohmite Manufacturing Company plant. The picture is the cover of the February 1945 issue of Radio News.

Goddard in 1926. Wikipedia image.

A hundred years ago this month, Electrical Experimenter magazine carried a feature about Prof. Robert Goddard, and his vision of sending a rocket to the moon. Goddard didn’t originally set out to go to the moon, his initial rockets were designed to explore the upper atmosphere of the Earth.

But there was a practical problem–above about 300 miles, there would be no way to prove how high the rocket had flown. With no atmosphere, it wasn’t possible to use an altimeter, the idea of radar hadn’t yet come to the fore, and there was really no practical way for the rocket to send a radio signal back to Earth.

Since a rocket going that high has hit the escape velocity, then it really wasn’t any extra trouble to go all the way to the moon. So Goddard envisioned packing the rocket with a load of magnesium powder, and crashing the craft into the “dark side” of the moon. (And yes, the term “dark” side was used correctly–meaning the part that is dark, even if facing the Earth.) With a sufficient charge, the resulting flash would be plainly visible from the Earth.

It was only 39 years later that the first craft reached the vicinity of the moon, the Soviet Luna 1 in 1959. And it was only a half century later that the first human walked on the surface of the moon.

In 1920, we were half a century away from being able to go to the Moon. Sadly, though, we can say the same thing about our present day. We’re a half century away from a human walking on the moon.

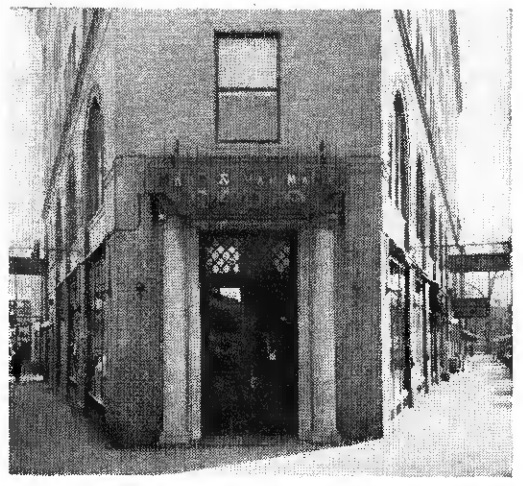

Seventy-five years ago, this trapezoidal building was the home of Mahr & Van Name, a radio dealer at 29 Beach Street, Stapleton, Staten Island, New York. The shop was featured in the February 1945 issue of Radio Retailing.

Seventy-five years ago, this trapezoidal building was the home of Mahr & Van Name, a radio dealer at 29 Beach Street, Stapleton, Staten Island, New York. The shop was featured in the February 1945 issue of Radio Retailing.

According to the magazine, both before and during the war, the shop stressed quality and material, rather than selling on a grand scale. With wartime shortages, that philosophy proved to be especially important.

Even before the war, the shop also sold table lamps, and those sales, along with service, kept the store open during the war. The owner predicted big things for both FM and TV, both of which the store had sold before the war.

As shown from the current Google Street View shot, the building still stands, although its unclear who occupies the radio shop’s former space.