The ARRL recently made a Petition for Rulemaking with the FCC. The request boils down to giving Technician class licensees some phone and digital privileges on 80, 40, and 15 meters.

The ARRL recently made a Petition for Rulemaking with the FCC. The request boils down to giving Technician class licensees some phone and digital privileges on 80, 40, and 15 meters.

I think this is long overdue, since it will allow Technicians, holders of what is now the entry-level license in Amateur Radio, some minimal but meaningful privileges on HF, similar to what I had as a beginner over 40 years ago.

The Entry-Level License in 1974

When I was first licensed, the entry level license was the Novice class. I had to pass a simple multiple-choice test, as well as a simple 5 WPM code test. When I did so at the age of 12, I was allowed meaningful HF privileges. And in my case, it wasn’t until I actually received the privileges that I realized how meaningful they were.

Before I got the license, I realized conceptually that hams could communicate around the world. But I didn’t really believe it. I assumed, incorrectly it turns out, that to really get out, you needed a lot of power and/or a big antenna. I assumed, incorrectly it turns out, that with 75 watts and a wire antenna, I would be able to get out locally, and maybe with good conditions, I might make occasional contacts with the next state. But I didn’t really believe that I would be able to communicate around the country and around the world on a regular basis.

Before I got the license, I realized conceptually that hams could communicate around the world. But I didn’t really believe it. I assumed, incorrectly it turns out, that to really get out, you needed a lot of power and/or a big antenna. I assumed, incorrectly it turns out, that with 75 watts and a wire antenna, I would be able to get out locally, and maybe with good conditions, I might make occasional contacts with the next state. But I didn’t really believe that I would be able to communicate around the country and around the world on a regular basis.

Nobody told me this. In fact, I was told the opposite. But I didn’t quite believe it. I didn’t believe it until I actually got on the air. When I did get on the air, I was soon filling up my log with contacts from all over the United States. Eventually, when I discovered 15 meters, I was getting out all over the world, all with 75 watts and some wire in the air.

What got me licensed in the first place was a somewhat undefined interest in radio and electronics. What got me hooked was the realization of how much fun it was to bounce my radio waves off the ionosphere whenever I wanted. New licensees need the same thing to get hooked today, but it’s not readily available.

The Entry-Level License Today

New hams today don’t have this same opportunity. The entry-level license is now the Technician license, with privileges mostly on VHF. As a practical matter, this means that most of them get an inexpensive handheld such as the Baofeng UV-5R shown here.

New hams today don’t have this same opportunity. The entry-level license is now the Technician license, with privileges mostly on VHF. As a practical matter, this means that most of them get an inexpensive handheld such as the Baofeng UV-5R shown here.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this radio. In fact, for the price, it’s amazing what it will do, and I’ve written about it previously. But this is the opposite of how I got started. I started on HF, and was able to bounce signals off the ionosphere, an activity that greatly exceeded my expectations. From the very first day I was licensed, I was able to interfere with Radio Moscow, and I did! Only after I had upgraded, to either General or Technician, was I able to get on VHF. At the time, that was something of an incentive, because there was a great deal of local repeater activity. Long before the age of cell phones, I was able to communicate with a handheld device, and even make phone calls. But an HT such as this really doesn’t have much capability beyond that of even the cheapest cell phone. It’s hardly an upgrade. In fact, in many areas, 2 meter FM is practically vacant. Repeaters are still up and running, but there are generally only the same handful of local operators day in and day out.

Technicians are also currently allowed to use SSB and data on 10 meters. This is somewhat of an improvement, since this band occasionally opens up to worldwide communications. Unfortunately, it’s not open most of the time. This is very different from my experience as a novice. With just one band, 40 meters, I could talk to someone almost any hour of the day or night. During the day, it would be 500 miles or so. At night, it would be over most of the continent.

Current technicians are also currently allowed to use CW (Morse code) on 80, 40, and 15 meters, and I think they should take advantage of this opportunity. But unfortunately, unlike when I was first licensed, there aren’t too many people willing or able to teach them the code and help them get on the air. And there’s also the question of price, since the cost of a radio for CW (or SSB) is often considerably more than the cost of a digital radio.

Digital Modes for New Licensees

The ARRL’s proposal will allow new licensees to do exactly what I did over 40 years ago: With inexpensive equipment, they would be able to get on the air immediately with digital signals on the lower HF bands. They would be immediately bouncing signals off the ionosphere, just like I did 40 years ago.

This can currently be done with equipment that costs about $125, assuming that they already own a computer, tablet, or smartphone. If there was a demand for the product, there would be other models available, probably at a lower price, and it would also be possible for them to make it in a group-build of a kit project.

UT5JCW Digital Transceiver.

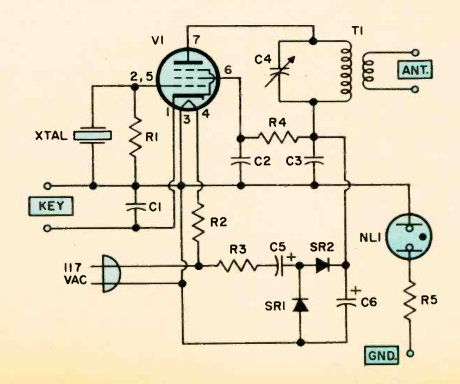

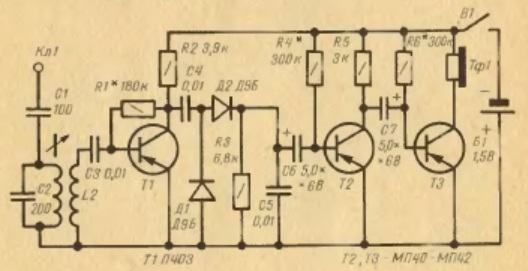

Currently, the only standalone digital rig available are a set of transceivers produced by UT5JCW in Ukraine. They plug directly into a computer, and can be used for all digital modes, including JT65, FT8, and PSK31. They require only a simple antenna, which could be as simple as a quarter-wave piece of wire strung in the backyard. For 40 meters, the band I would recommend for a beginner, this would be 33 feet long.

With a radio such as this one, a new ham could be on the air almost immediately, making meaningful contacts all around the country. It would be a much more meaningful introduction to ham radio than simply talking with the same handful of locals on a 2 meter repeater.

And the cost could be very comparable. As noted above, the only radio currently on the market costs $125 shipped from Ukraine. But this hasn’t always been the case. Until several years ago, a kit called the PSK Warbler was available in kit form for about $40. With guidance (perhaps as part of a licensing class), construction of such a kit was within the expertise of even a beginner.

I think that there could be a very meaningful introduction to ham radio if beginners were able to get their license and start out right away with a radio such as this one. It would be more or less the functional equivalent of how I got started on 40 meter CW 40 years ago.

Is Today’s Test Really Easier?

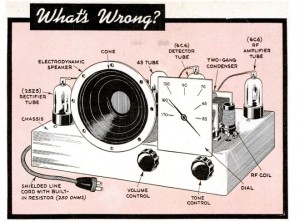

One argument against changing the rules is that the test has allegedly been “dumbed down” over the years, and that beginners should not be given HF privileges until they have taken a test that is sufficiently difficult.

One argument against changing the rules is that the test has allegedly been “dumbed down” over the years, and that beginners should not be given HF privileges until they have taken a test that is sufficiently difficult.

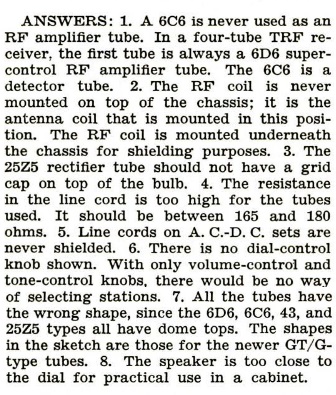

However, this argument is based on a false premise. When I took the test for the entry-level test in early 1974 at the age of 12, it was much easier than the current Technician exam. I had to take a 20 question multiple choice test. That test was very easy: I had to memorize the meaning of some new vocabulary words (such as “pecuniary”). I had to learn some pieces of trivia. For example, I had to know that transistors were made out of silicone and geranium. (Actually, it turns out that it’s silicon and germanium, but that was close enough.)

I had to memorize a few equations, such as Ohm’s law. I didn’t need to understand what was going on. I needed to know, for example, that if the question included the words “Volts” and “Ohms”, then I needed to divide Volts by Ohms, and that was the right answer. I also had to memorize the formula for the length of a dipole antenna, 468/f.

I was well aware that there was going to be one complicated word problem on the test. This appears as question number 46 below, which called for me to calculate the input power to a final amplifier stage. I knew to an absolute certainty that this question was going to be on the test, and it was there, more or less verbatim. The only thing that changed was the actual numbers. I had to ignore the filament numbers. Like any word problem, irrelevant information was included. I had to multiply screen voltage and screen current, and then multiply plate voltage times plate current. Then, I added up those numbers, and also added drive power. And sure enough, when I did this, even if I didn’t really understand what was going on, that number was one of the multiple-choice answers.

To give some idea of how easy the novice test was, I scanned the novice questions and answers from the 1975 license manual. By simply reading these six pages, and making sure that some critical facts were memorized, it was almost certain that anyone attempting the test could pass with flying colors, even if, like me, they didn’t really understand most of the material.

Here are those six pages from the 1975 license manual. These questions might have changed slightly from when I took it in 1974, but they are almost identical. (To download these pages to your computer as a PDF file, use this link.)

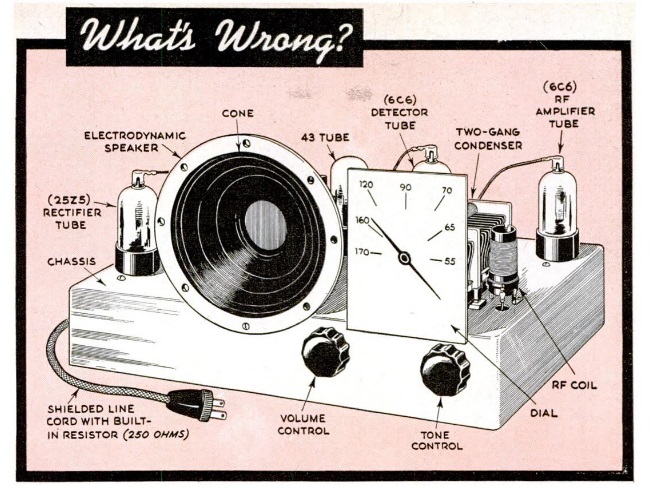

As you can see, there are a couple of questions in the study guide asking you to draw a particular circuit. However, the exam was strictly multiple choice, and it was known in advance that it was multiple choice. So there might have been a question with the drawing asking to name a part, or identify a missing part. But I didn’t have to draw any diagrams, and I knew going in that I wouldn’t have to.

Basically, just about anyone could have passed the Novice license test 40 years ago after reading these six pages. I’m the author of a study guide for the current Technician exam, and I use 160 pages to explain the material. Yes, I probably go into a bit more detail than the License Manual did 40 years ago, but I didn’t include much excess details. Based upon my familiarity with both exams, I would say that the test I took was a lot easier, yet it gave me the opportunity to interfere with Radio Moscow.

Basically, just about anyone could have passed the Novice license test 40 years ago after reading these six pages. I’m the author of a study guide for the current Technician exam, and I use 160 pages to explain the material. Yes, I probably go into a bit more detail than the License Manual did 40 years ago, but I didn’t include much excess details. Based upon my familiarity with both exams, I would say that the test I took was a lot easier, yet it gave me the opportunity to interfere with Radio Moscow.

In other words, it’s simply not true that the entry-level license test today is easier than it was 40 years ago. It’s not much more difficult, but I was never required to take a difficult test before getting on HF. There’s no reason why the same thing shouldn’t be true today.

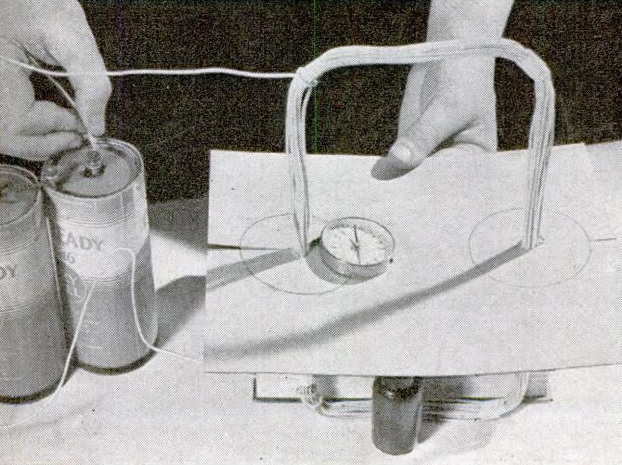

If you’re reading this page because Junior just remembered that the science fair project needs to be handed in tomorrow, there’s no need to panic! This site is full of interesting science fair projects. Some of those projects might take some time to complete, but many of them can be whipped into shape in an evening. This one falls into that category. Junior can make an impressive display by mapping magnetic lines of force.

If you’re reading this page because Junior just remembered that the science fair project needs to be handed in tomorrow, there’s no need to panic! This site is full of interesting science fair projects. Some of those projects might take some time to complete, but many of them can be whipped into shape in an evening. This one falls into that category. Junior can make an impressive display by mapping magnetic lines of force.

The

The