Monthly Archives: March 2018

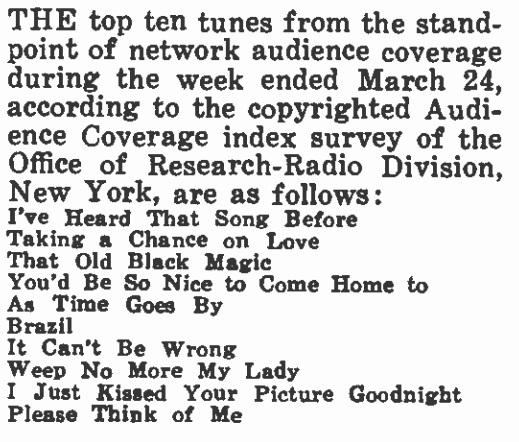

1943 Top Ten

Here are the top ten songs of the week 75 years ago, according to the March 29, 1943, issue of Broadcasting magazine. For your listening pleasure, here are links to the songs:

- I’ve Heard That Song Before (Harry James/Helen Forrest)

- Taking a Chance on Love (Benny Goodman/Helen Forrest)

- That Old Black Magic (Glenn Miller/Skip Nelson)

- You’d Be So Nice to Come Home to (Dinah Shore)

- As Time Goes By (Rudy Vallee)

- Brazil (Xavier Cugat)

- It Can’t Be Wrong (Dick Haymes)

- Weep No More My Lady (Frank Sinatra)

- I Just Kissed Your Picture Goodnight (Dennis Day)

- Please Think of Me (Shep Fields)

1948 Ham Station

This compact but well equipped ham station from 70 years ago is shown on the cover of the March 1948 issue of Radio News.

This compact but well equipped ham station from 70 years ago is shown on the cover of the March 1948 issue of Radio News.

The unidentified station features the control for the rotary beam, Hallicrafters SX-43 receiver, a wire recorder, Hallicrafters HT-18 exciter, and panadapter. Not shown is the remotely controlled BC-610E transmitter being driven by the HT-18.

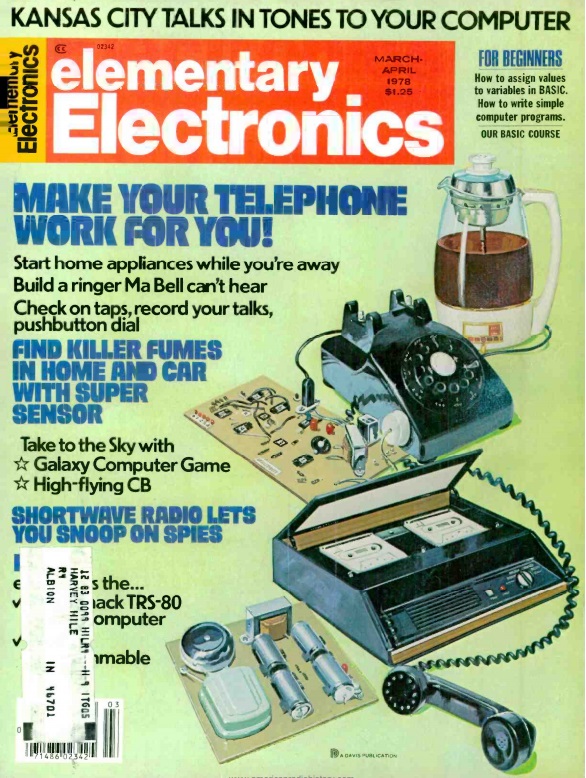

1978 Telephone Ideas

Forty years ago this month, the March-April 1978 issue of Elementary Electronics carried a number of articles on ways to make your phone work for you. These involved both commercial products and homemade projects.

Forty years ago this month, the March-April 1978 issue of Elementary Electronics carried a number of articles on ways to make your phone work for you. These involved both commercial products and homemade projects.

The magazine noted that Ma Bell’s iron grip on telephone equipment was just starting to loosen. It noted that in the recent past, it was forbidden do do as much as add a piece of felt to the bottom of the phone to keep it from scratching a table, or put a shoulder rest on the receiver. Still, it advised you to check with the phone company before using any accessories–and not to give your name or address when you called!

The phone company would install four-prong jacks (for a fee). If you had only one jack, you could use cube taps to plug in more than one device. Plugs with a built-in socket were also available, which allowed you to stack as many as needed into a single outlet.

One of the homemade projects shown in the magazine was the remote control shown hooked to the coffee pot in the picture. This device would be legal anywhere, since it had no direct connection to the phone line. But it allowed you to turn appliances on by remote control at no cost.

Instead of a connection to the phone, it simply contained a microphone which was placed near the phone, and it was operated (at no cost) by the phone’s bell. To turn the appliance on, you called yourself, let it ring two times, and then hung up. Then, you would call again between 20 and 40 seconds later and let it again ring twice. The appliance would turn on only with this exact sequence, thereby almost eliminating the risk of the coffee being turned on by a random caller.

Also shown was a loud external ringer to ensure that you never missed an important call.

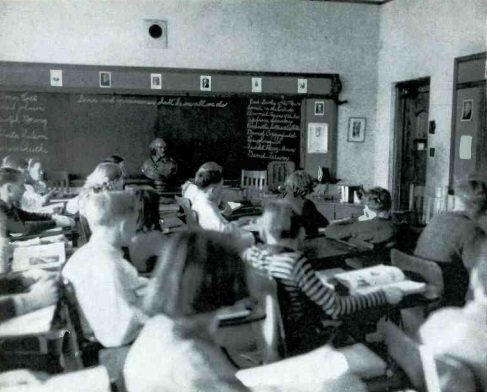

WLS School Time, 1938

Shown here from 80 years ago are seventh-grade students at Emerson School, Maywood, Illinois, receiving some of their instruction from the radio strategically stationed on the teacher’s desk.

Shown here from 80 years ago are seventh-grade students at Emerson School, Maywood, Illinois, receiving some of their instruction from the radio strategically stationed on the teacher’s desk.

The picture is from the March 1938 issue of Rural Radio magazine, which contained an article describing the School Time program broadcast each school day at 1:00 on WLS in Chicago. The service began on February 8, 1937, and during its first year, it had been listened to regularly by 1200 schools in Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan. The Cook County superintendent of schools reported that more than 40,000 students in that county alone were listening regularly.

The program was designed to bring into the classroom experiences and information that the students might not otherwise obtain. On Monday’s, for example, the program included a newscast. Since most radio news reports were aimed at older listeners, the WLS program added dialogue, drama, and interview to the news program to capture the interest of the younger listeners.

One niche served by the station was music education. Especially in smaller schools, very little musical training was available. Therefore, the Tuesday program was a musical tour of the globe with folk songs of all nations.

Wednesdays featured visits to industries of different kinds, and Thursdays focused on geography, with listeners meeting a foreign gues star from the country being studied.

Fridays had a different program each week, covering Good Manners, Recreation, an outdoor program, and a program focusing on children’s literature.

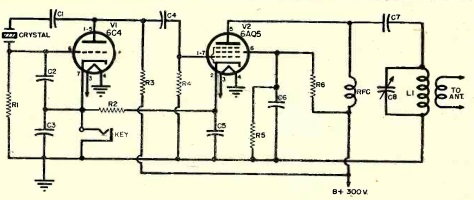

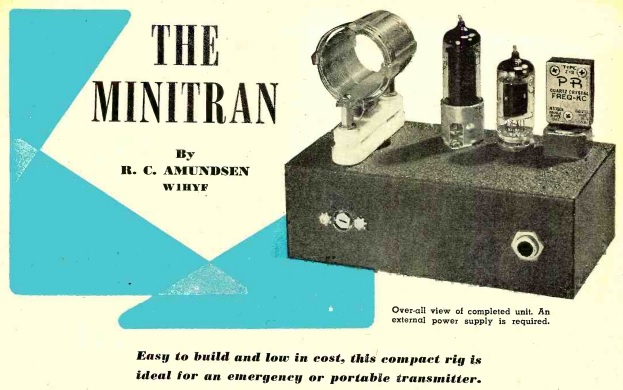

1948 Two Tube Transmitter

The March 1948 issue of Radio News carried the plans for this two-tube transmitter for 40 or 80 meters, ideal for portable or emergency use.

The March 1948 issue of Radio News carried the plans for this two-tube transmitter for 40 or 80 meters, ideal for portable or emergency use.

The author noted that most ham transmitters weren’t suited for such purposes due to their size, weight, and inflexibility of power supply. This “MiniTran” was built with those constraints in mind. The author settled on a two-tube design after difficulties with keying a one-tube design were encountered, especially with makeshift equipment. The circuit uses a 6C4 Pierce Oscillator driving a 6AQ5 output.

The circuit required 6 volts for the filaments, and 300 volts B+, which could be derived either from a vibrator power supply, or simply by tapping into the receiver’s power supply.

When the author got the rig on the air, he made a contact with the first station called on 40 meters, which was a contact with Tennessee from Connecticut. In the next week, seven more states were worked on 80 and 40, with reports as high as RST 589X.

Brox Sisters

Shown here in the mid-1920s are the Brox Sisters tuning in to some program on their radio.

Shown here in the mid-1920s are the Brox Sisters tuning in to some program on their radio.

The Brox Sisters, Patricia, Bobbe, and Loryane, (left to right in the photo) grew up in Tennessee and began touring the U.S. and Canada on the Vaudeville circuit in the 1910’s, and at the start of the 1920’s, they moved to Broadway, where they performed in Irving Berlin’s Music Box Revue from 1921 to 1924. They also appeared on stage with the Marx Brothers and the Ziegfeld Follies of 1927. They also appeared in a number of movies, both shorts and feature films, in the 1930’s.

The sisters can be heard in this 1929 recording of Singing In The Rain:

Midwest Blizzard of 1949

Downtown Rapid City. National Weather Service/Rapid City Journal.

As I write this, snow is once again forecast for my region. Since the calendar says that it’s the first day of spring, it’s likely that the snow will be little more than a temporary inconvenience.

But I was recently reminded that a snowstorm wasn’t always just a minor inconvenience, and I learned about one of the Midwest’s largest winter storms ever, the blizzard of January 2-5, 1949.

I don’t think I had ever heard about this storm until I had a comment on my post about KGFX, a one-woman broadcast station run out of the home of Ida McNeil in Pierre, SD. As I mentioned in the previous post, Mrs. McNeil did take commercial advertising, but she viewed the station mostly as a public service. And this is borne out from the story of the 1949 blizzard shared by reader Dwight Small:

I well remember her broadcasting during the blizzard of 1949. We were completely snowbound on the former Hugh Jaynes ranch 15 miles NNW of Pierre. She was our only window to the outside world for at least a couple of weeks. We had no electricity but the battery powered radio lasted sustained our spirits. We learned from her that there were hundreds of others in the same boat.

I did some research about the storm, and it appears that many were, indeed, in the same boat. The winter of 1948-49 was severe in many respects, but it delivered it’s biggest punch to the northern plains in the early days of January, 1949.

The April, 1949, issue of QST describes its entry to South Dakota:

Things began on the morning of January 3rd in South Dakota, when KOTA, Rapid City’s broadcaster, let loose with the first hint that the impending storm was to be of record-breaking proportions. Unfortunately many ranchers, traveling people and others failed to hear the broadcast warnings and were totally unprepared for what was to come. It started coming down on the 3rd, and continued until about noon on the 5th. The actual snowfall was not of record-breaking proportions, but high winds, sometimes in gusts of 65 to 70 miles per hour, piled the snow into mountainous drifts, oftentimes 30 to 50 feet deep.

Many others found themselves isolated by the storm. In 2013, the Rapid City Journal carried the reminiscence of schoolteacher Grace Roberts, who was stranded at her post in Creighton, a small town about 25 miles north of Wall. She and her four-year-old daughter made it to school, but then found themselves trapped there for 38 days. The road to the school was plowed a few times, but was quickly covered over with snow.

She reminisced in 2013 that she ate a lot of canned soup, but managed due to the kindness of neighbors, the closest of whom was a mile away. The neighbor would ride over on horseback, “and when his wife baked bread he’d bring us some bread or when he milked a cow, he would bring some milk.”

The school had a small bed, and was well stocked with coal. They also had a battery radio, and would listen occasionally, but mostly passed the time by talking and reading.

Another survivor, Everett Follette of Sturgis, like many South Dakotans, had a phone line that kept working through the storm and served as the lifeline. Interestingly, though, Follette recounted in 2009 that the family also had a battery-powered radio, “but the only station they could tune in came from Bismarck, N.D.”

Battery radio of the era, a Philco 41-841.

The family used as much milk and cream as they could from their dairy farm, but with roads impassible, they had to dump the excess. Eventually, the Sturgis creamery called about the availability of milk, and made a deal to follow a military snowblower. When neighbors learned that the truck was coming, they quickly phoned the grocery store in Sturgis to have groceries delivered.

As might be expected, hams sprang to action to deal with the communications needs of the region, as detailed in the April 1949 issue of QST. In South Dakota, when the snow first started coming down, W0ADJ and W0CZQ made arrangments with the Air Force base to maintain contact with the base at Colorado Springs, “just in case.” Hams also played a role in coordinating the massive air operations after the storm had passed. Planes were used to search for survivors and drop supplies for both humans and livestock.

Broadcast stations advised incommunicado ranchers of which marks to make in the snow to request drops of feed and other supplies.

One of the most dramatic uses of amateur radio took place in Ogallala, NE, a town of about 3000 in western Nebraska. A train was stalled in the snow west of town, and a major transcontinental highway was blocked. State snowplows managed to break through, and led a mile-long convoy of cars into town. Suddenly, the town of 3000 was pressed into service to shelter, feed, and supply communications for an additional 2000 people.

The communications duties fell upon W0LOD, the town’s only ham, whose station was limited to running 50 watts with a single 807, and only on 40 meters. Despite his modest station, “all around W0LOD–north, south, east and west–were hams with sensitive receivers, and perhaps greater power, and, as the skip ebbed and flowed he was able to sit at his operating position handling emergency traffic in unbelievable quantity much as he had been accustomed to handle routine traffic night after night. It was a 48-hour session at the key, but no heroics, no frantic ‘QRRR’–just a traffic man doing that which he likes best.”

The April 1949 QST article tells of other storms that winter, many of which overlapped each other. For example, when railroad telegraph lines went down, hams were called upon to assist the railroads in keeping te trains running. In Kansas, W0EQD didn’t even realize that his town had been cut off from the outside world. The power was out, so he got his station running on the emergency generator and checked into the Kansas Phone Net, which had traffic waiting for the phone company. As soon as he delivered the message and local officials found out he was on the air, he was kept busy for the next 48 hours as his town’s only communications facility.

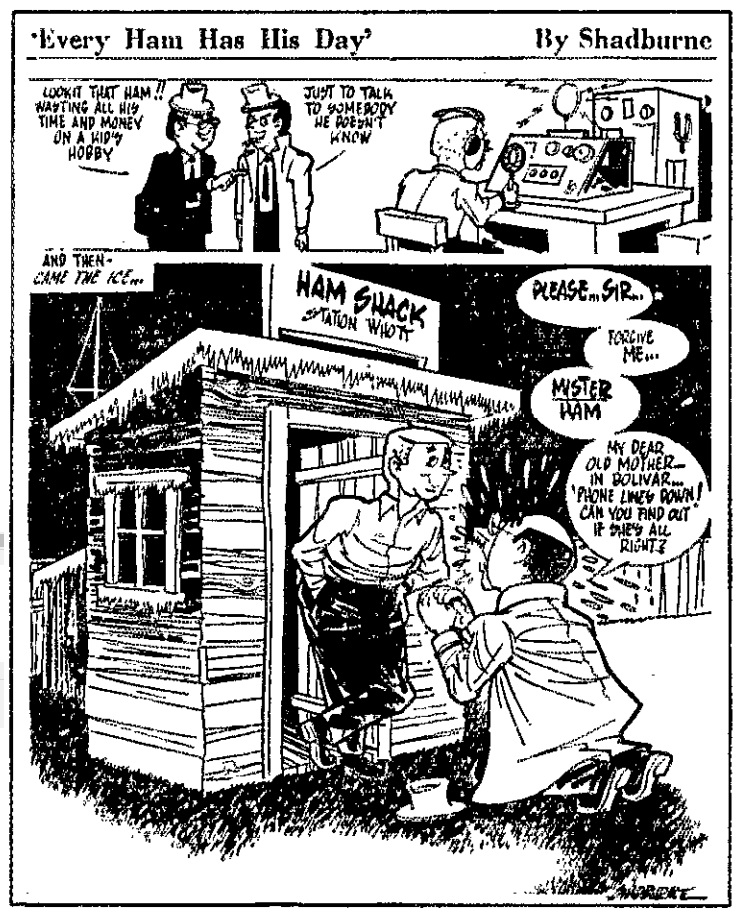

Missouri was hard hit by an ice storm on January 11, and many commercial telegraph lines were down. Western Union called on hams to deliver both company and weather bureau messages. The cartoon below appeared in the Springfield (Mo.) News & Leader, and was reprinted in QST. It shows a ham being scoffed for spending so much time and money to take part in a “kid’s hobby” only to talk to people he didn’t even know. But in the next panel, after the ice hits, the same man is begging the ham to get news of his mother who was cut off from the outside world.

References

It’s ‘Going Down in History”: The Blizzards of 1949. South Dakota History Vol. 29, p. 263 (1999).

Albert E. Hayes, Jr., W1IIN, Deep Freeze, QST, Apr. 1949, p. 35.

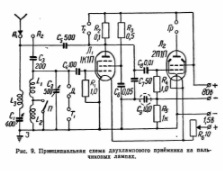

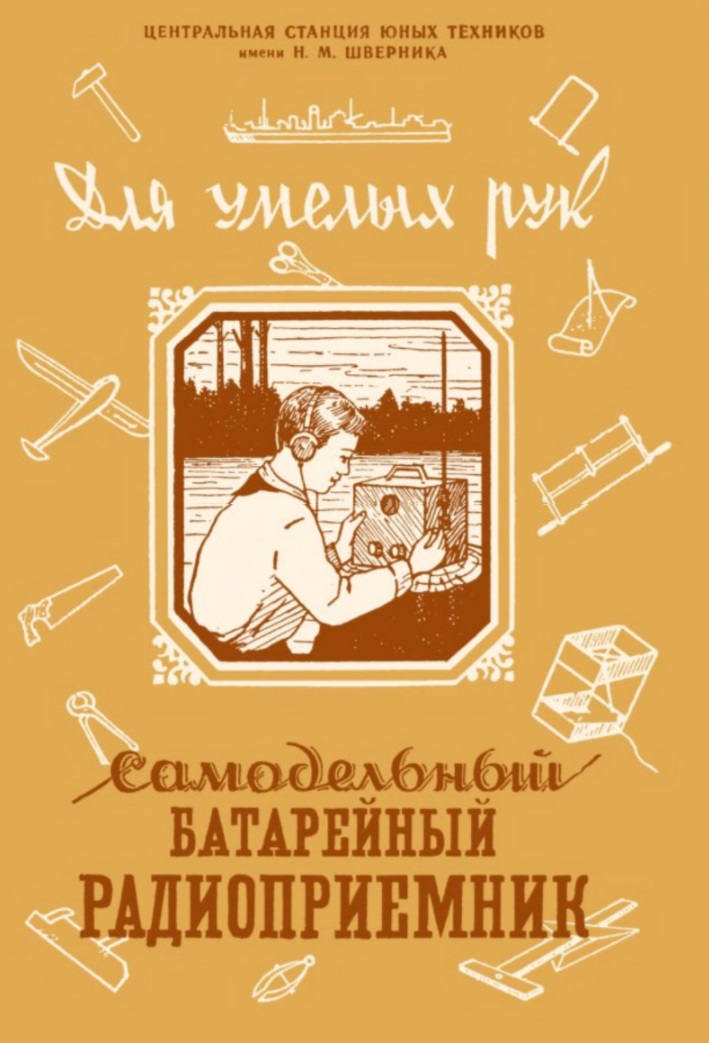

Three Soviet Battery Receivers

The young comrade shown here is pulling in the latest bulletins from Moscow thanks to the battery powered receiver he built himself, courtesy of the plans contained in a little booklet entitled, Самодельный батарейный радиоприемник (Homemade Battery Radio), published in 1956 as part of the series Для умелых рук, (For skillful hands).

The young comrade shown here is pulling in the latest bulletins from Moscow thanks to the battery powered receiver he built himself, courtesy of the plans contained in a little booklet entitled, Самодельный батарейный радиоприемник (Homemade Battery Radio), published in 1956 as part of the series Для умелых рук, (For skillful hands).

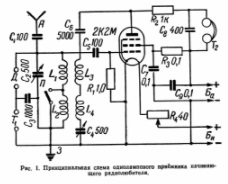

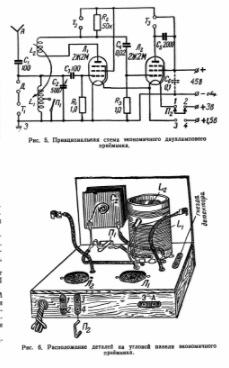

There are actually three different sets included, both one and two tube models. They appear to cover medium wave (200-500 meters) and long wave (800-2000 meters).

There are actually three different sets included, both one and two tube models. They appear to cover medium wave (200-500 meters) and long wave (800-2000 meters).

The first set is a one-tube model using a 2К2М tube,  shown at left. The single tube serves as regenerative detector, with the switch near the coils switching from mediumwave to longwave. The second model, shown at the right, uses a second 2К2М as an audio amplifier. The final set, shown below, uses a 1К1П detector and 2П2П audio amplifier. All are apparently designed to run from a БАС-80 battery supplying filament voltage and 45 volts B+.

shown at left. The single tube serves as regenerative detector, with the switch near the coils switching from mediumwave to longwave. The second model, shown at the right, uses a second 2К2М as an audio amplifier. The final set, shown below, uses a 1К1П detector and 2П2П audio amplifier. All are apparently designed to run from a БАС-80 battery supplying filament voltage and 45 volts B+.

I found this web page showing a modern reconstruction of a circuit almost identical to the first one-tube design shown here. According to the site, the design was originally published by F.I. Tarasov in 1949. In fact, I see Tarasov’s name cited in this booklet as well.

The main modification seems to be a potentiometer added to adjust the filament voltage, along with a voltmeter to monitor it. The page is in Russian, but Google translate does an excellent job of translating it. The video below shows the completed receiver in use, and it appears to be a good performer:

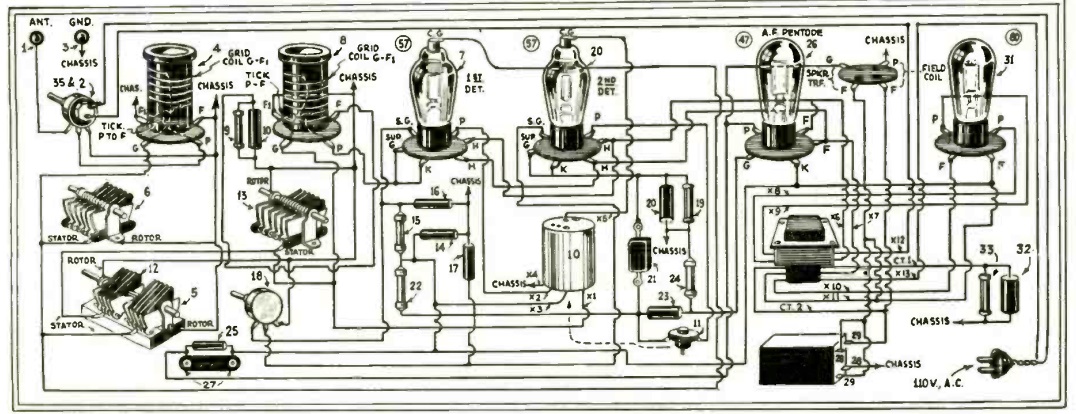

1933 Four Tube Superhet

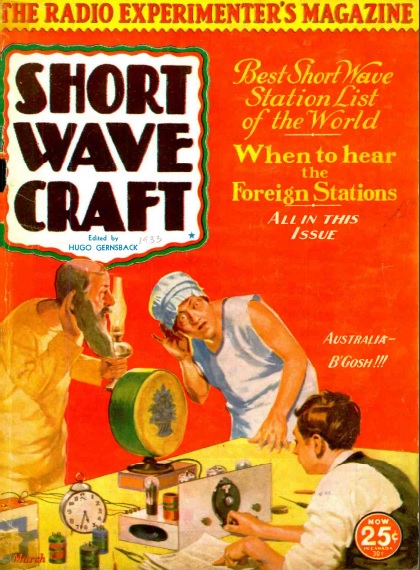

85 years ago this month, we see this young radio enthusiast who just managed to wake up his parents at 5:30 in the morning. When they came to investigate, they were shocked to learn that he was pulling in Australia with the four-tube superheterodyne described in the March 1933 issue of Short Wave Craft magazine.

85 years ago this month, we see this young radio enthusiast who just managed to wake up his parents at 5:30 in the morning. When they came to investigate, they were shocked to learn that he was pulling in Australia with the four-tube superheterodyne described in the March 1933 issue of Short Wave Craft magazine.

The set employed two tubes in the RF section with an additional tube serving as AF amplifier. The set ran off AC power, and contained a power transformer and rectifier completing the tube lineup.