Today, almost every auditorium of any description is wired for sound, and we take for granted that someone will turn on the PA, and we’ll be able to hear what’s going on through the ubiquitous speakers.

But this hasn’t always been the case. We take the presence of the sound system for granted. But until the early 20th century, there was an absolute prerequisite for orators of any type: They needed to have a loud voice in order to be heard.

This was particularly true of churches. There was one qualification for ministers that was even more important then their theological bona fides: They had to be loud, since their sermon had to fill the sanctuary on its own power, without the aid of any electrical amplification.

This began to change in the 1920’s and 1930’s, as the “sound man” became an important player in the field of electronics. Wiring halls of any type for sound became a lucrative profession. And with the advent of the microphone, amplifier, and loudspeaker, the sheer volume of the preacher’s voice became less and less of an issue.

A related issue was addressed by an article appearing 85 years ago this month in the March 1932 issue of Radio News. Electronic amplification could solve another problem, namely allowing those with poor hearing to fully participate in church services and other public events. Personal hearing aids worked well for conversation with another person nearby. But they were largely useless for picking up a speaker at the other end of a large auditorium. For that reason, churches and other public venues were beginning to wire what the article called “group hearing aids,” or what we would today call assistive listening devices.

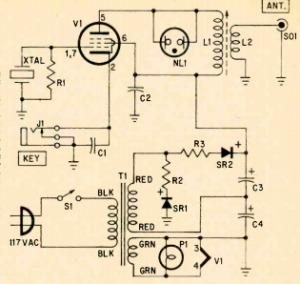

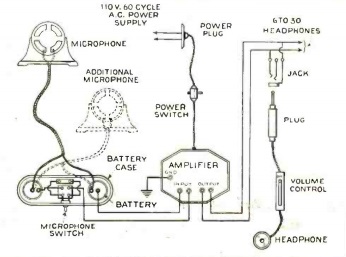

As seen from the schematic here, the circuit is quite straightforward. A microphone is placed near the pulpit, is amplified, and is then fed to telephone receivers with individual volume controls.

As seen from the schematic here, the circuit is quite straightforward. A microphone is placed near the pulpit, is amplified, and is then fed to telephone receivers with individual volume controls.

The article concluded by noting that the date was not far distant when those with defective hearing would be able to walk confidently into any hall or meeting place knowing that provision had been made for them to participate fully in one more phase of well-rounded living.

Modern assistive listening devices (ALD’s) are typically wireless, most frequently operating below the FM broadcast band at 72-76 MHz. You can read more about modern systems at my ALD receiver page.