A hundred years ago this month, the February 1917 issue of Popular Mechanics showed how a progressive second grade teacher used modern methods to teach her children spelling: She taught them by means of Morse Code.

As the article noted, it was a well-known truth that children learned more quickly through play than through dull hours of tedious instruction. The teacher, Miss Florence Biddle of Columbus, Ohio, discovered that she could make the children anxiously look forward to their daily spelling lesson by use of Morse code.

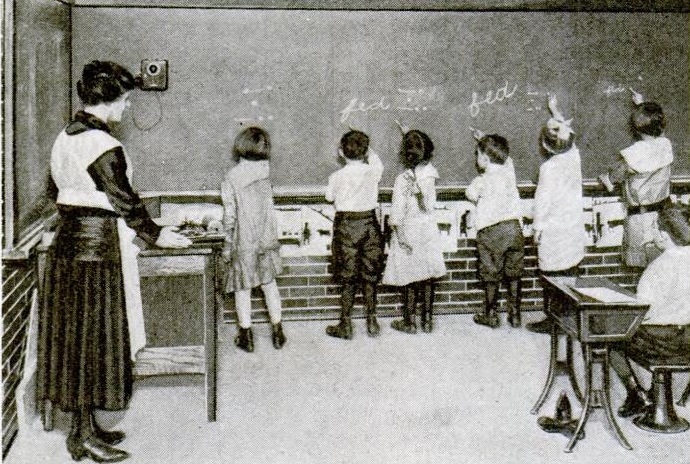

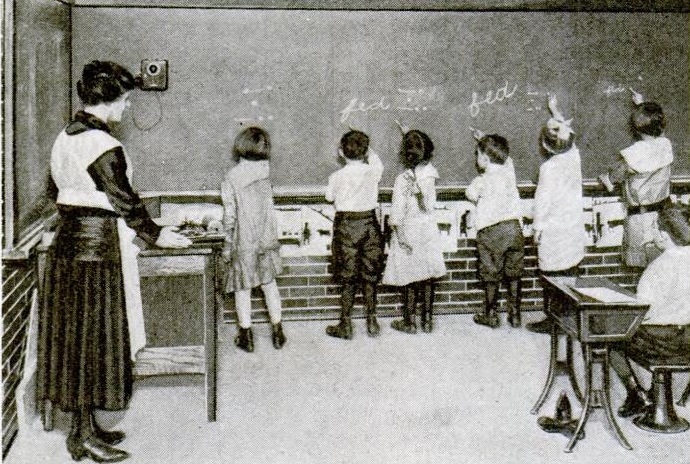

Miss Biddle would send words from a telegraph key at her desk. The children would then write down the dots and dashes and then translate them. Here, we can see that these children have correctly copied her send the word “fed.” The girl to the left has the dots and dashes written down, and the others have completed the process of translating. A variation in the lesson was having children send the code for words she dictated.

Miss Biddle’s method is explained in more detail in the April 1917 issue of Primary Education magazine.

According to that article, Miss Biddle’s method had spread from her own Spring Street School to other schools in the city. She originally got the idea four years earlier, and used a ruler to tap out the words. After Assistant Superintendent R.G. Kinkead saw the idea, he provided her with the telegraph instrument, and the idea spread.

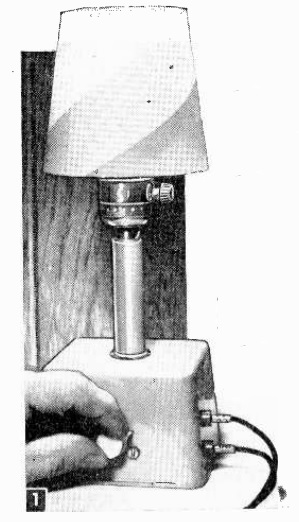

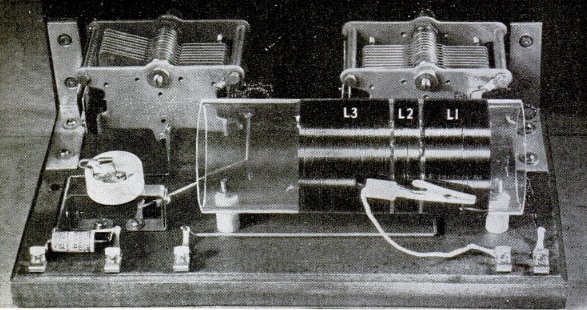

That article noted that the children like to learn the code, because it “puts them in touch with the railroad and telegraph, two things which fascinate all children.” Here, from that article, we see one of your young students sending a message in response to her dictation.

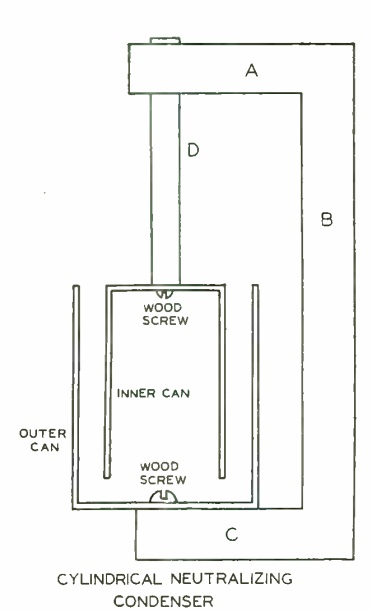

If you look carefully at the dots and dashes written by the student on the left, you see that Miss Biddle was teaching American Morse, since .-. is written down for “F”. This stands to reason, since she is using a landline telegraph sounder, and American Morse would have been in use by the railroads and telegraph companies. If any of these students were inspired to get into wireless telegraph, then they would have had to learn International Morse, which varies slightly. But their minds appear resilient, and I’m sure they would have had little trouble making the transition.