Eighty years ago this week, the United States was in the midst of one of its greatest natural disasters, the Ohio River flood of 1937.

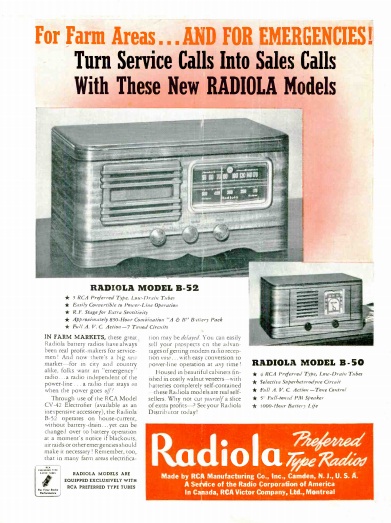

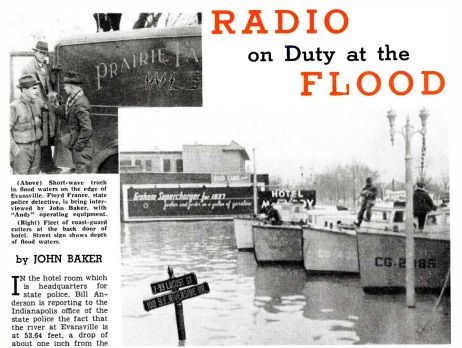

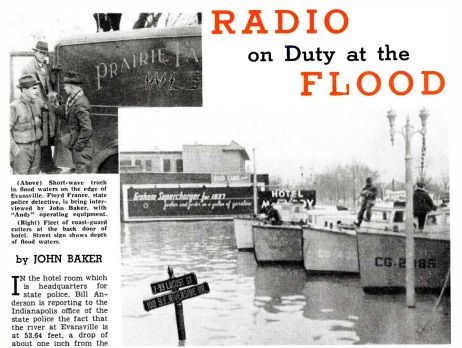

Damage was widespread, starting at Pittsburgh, which had experienced severe flooding the year before, to Cairo, Illinois. Damage was light in the Pittsburgh area, but there was extensive damage in Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. The pictures at the top of the page are from Evansville, Indiana, and appear in the February 13, 1937, issue of Stand By, the program guide magazine of WLS Chicago, whose mobile unit is shown. The boats shown in the picture, docked at the back door of a hotel, are actually on the street, as shown by the mostly submerged street sign in the picture.

The WLS magazine reported that “radio became the principal means of communication, especially during the early days of the flood, and thousands of lives were saved because of the radio directions sent to rescue workers. Commercial, amateur and military stations all provided communication.”

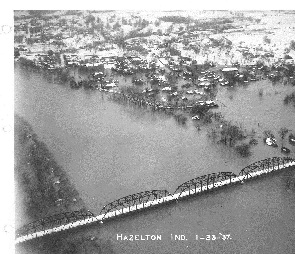

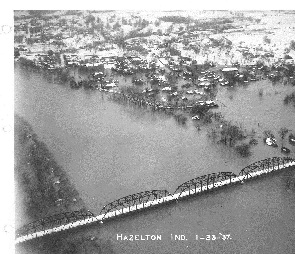

Hazelton, Indiana, January 23, 1937. National Weather Service photo.

In Evansville, the local station, WGBF, had an emergency radio set up at the relief headquarters. The station went to 24 hour service, and the programs were interrupted frequently to broadcast relief messages.

The flood caused 385 deaths, with a million left homeless. Property damage reached $500 million, and relief and recovery was strained, with the disaster coming in the depth of the depression and only a few years after the Dust Bowl. The head of the Red Cross called the disaster the greatest since the war. For many impacted areas, it was the most severe flood yet experienced.

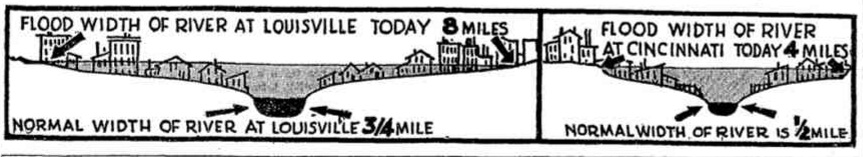

The water levels began to rise on January 5, and rains throughout the

Ohio basin continued. By January 23, it was clear that the flood would be severe. Martial law was declared in Evansville on January 23. On today’s date, the water crested in Cincinnati at 80 feet, the highest level in the city’s history. By the next day, 70% of Louisville was under water. It wasn’t until February 5 when the water levels dropped below flood stage in most areas.

As might be expected, amateur radio operators played a key role in communications, and many of these stories were recorded in the April, 1937, issue of QST. Since many of the active hams were also involved in the Army Amateur Radio Service or the Naval Reserve, Army and Navy call signs were often used in addition to amateur calls.

In an action unprecedented since the war, on January 26, the FCC entirely closed the 160 and 80 meter bands nationwide to all but those hams directly involved in flood relief. The FCC order stated:

To all amateur licensees: The Federal Communications Commission has been advised that the only contact with many flooded areas is by amateur radio, and since it is of vital importance that communications with flooded areas be handled expeditionsly, IT IS ORDERED that no transmissions except those relating to relief work or other emergencies be made within any of the authorized amateur bands below 4000 kilocycles until the Commission determines that the present emergency no longer exists.

This order was rescinded on February 5. The FCC did allow the ARRL to select 60 “vigilantes” to monitor the bands and inform any offenders of the order. According to QST, this order had a very positive impact in reducing interference. 160 and 80 meters were still packed with signals relaying emergency traffic, but the nets were able to work very effectively when they had the bands to themselves.

Hundreds of call signs in all of the affected states are included in the QST report, but it also acknowledges that it would be impossible to list all of the hams who participated.

The 30,000 residents of Parkersburg, West Virginia, were cut off from the outside world, and about a fourth of them were homeless. Herbert Romine, W8GDF, of nearby West Milford hurried to the town. Lacking sufficient equipment, he hurredly assembled several transmitters from the serviceman’s parts stock, and established stations on fire boats in the city. These hastily constructed transmitters consisted of type 45 tube oscillators, along with another 45 serving as modulator. QST noted that this work undoubtedly saved a number of lives.

Romine then put station WPAR in Parkersburg back on the air, having to dismantle and move it a number of times as the waters rose. Another ham, W8BRE, helped put together a 160 meter radio to link the station with the Naval Reserve station.

At Leon, WV, inactive ham Clarence Casto, W8JJA, had been off the air for three years. But with the emergency, he hastily assembled an emergency version of his station to keep the town in contact.

A few miles downstream in Point Pleasant, WV, William Stone, W8MAO, was able to use a portable 20 meter rig to notify authorities in Charleston that medical supplies were needed by air. This station was set up in the court house on the judge’s bench.

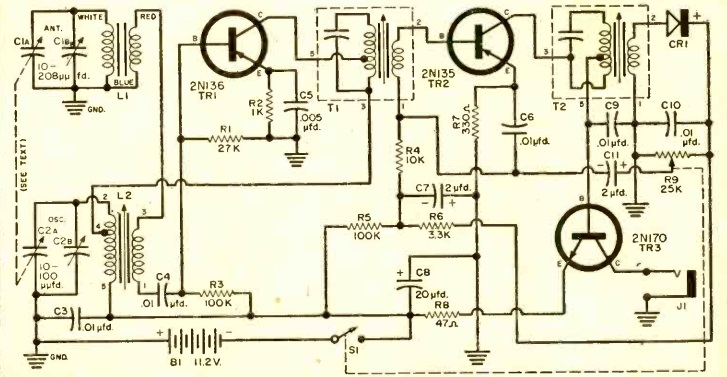

In Ohio, much of the relief traffic passed through W8YX, the club station of the University of Cincinnati. Since commercial power had become unavailable, the station operated with the generator setup shown here. Two 15 kva alternators were run by the power takeoff of a McCormick-Deering tractor.

In Ohio, much of the relief traffic passed through W8YX, the club station of the University of Cincinnati. Since commercial power had become unavailable, the station operated with the generator setup shown here. Two 15 kva alternators were run by the power takeoff of a McCormick-Deering tractor.

In Kentucky, since Frankfort was cut off and flooded, the Governor of the state relied upon an amateur for emergency communications. W9AZY, who was also affiliated with a broadcast station, was able to set up a shortwave link between the Governor and his staff and broadcast station WLAP.

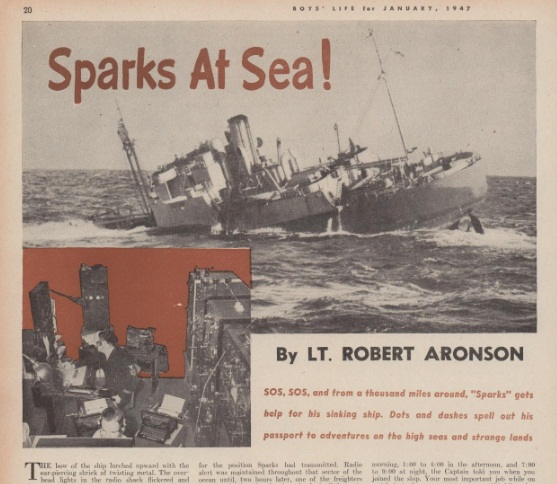

The man identified as “one of the flood’s ham heroes” was W.O. Bryant, W9NKD. On January 22, WHAS in Louisville broadcast the information that Carrollton, KY, population 2500, had been cut off from the outside world. The broadcast included a plea for an amateur to go there with emergency equipment. Bryant answered the call and brought his equipment by boat, where he was the only source of communications for 10 days. Another such amateur is shown to the left, W9MWC, taking emergency equipment by boat to Shawneetown, KY, in temperatures of 12 degrees and sleet.

The man identified as “one of the flood’s ham heroes” was W.O. Bryant, W9NKD. On January 22, WHAS in Louisville broadcast the information that Carrollton, KY, population 2500, had been cut off from the outside world. The broadcast included a plea for an amateur to go there with emergency equipment. Bryant answered the call and brought his equipment by boat, where he was the only source of communications for 10 days. Another such amateur is shown to the left, W9MWC, taking emergency equipment by boat to Shawneetown, KY, in temperatures of 12 degrees and sleet.