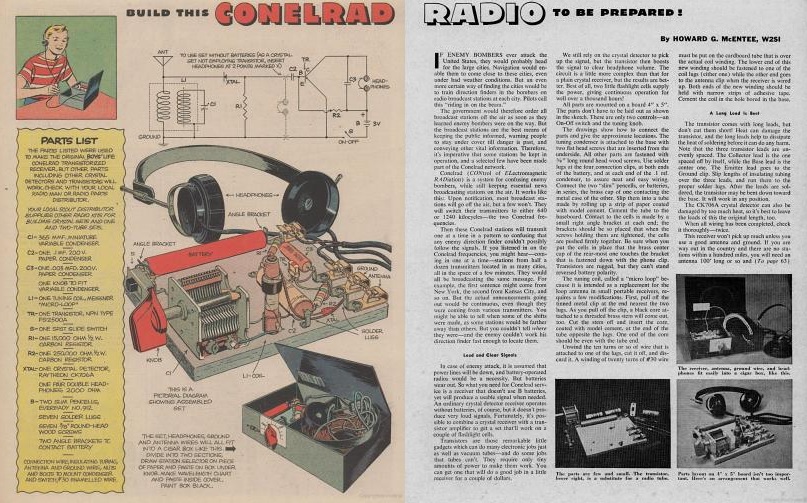

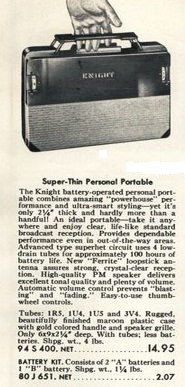

In the mid-1950’s, a transistor radio was an expensive luxury. This presented a problem for an impecunious Boy Scout who wanted to Be Prepared for anything. In the words of Boys’ Life magazine for January 1956, “in case of enemy attack, it is assumed that power lines will be down, and battery-operated radios would be a necessity. But batteries wear out. So what you need for Conelrad service is a receiver that doesn’t use B batteries, yet will produce a usable signal when needed.”

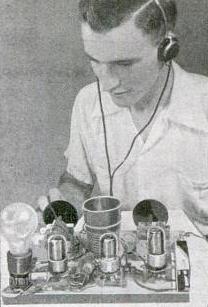

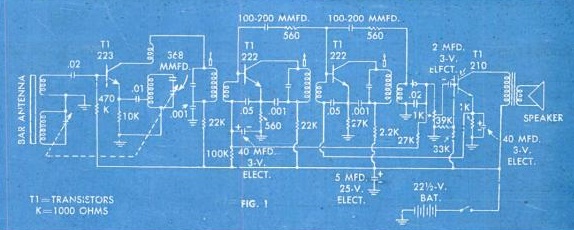

The article pointed out that a crystal set might be pressed into service, but wouldn’t produce very loud signals. Fortunately, Boys’ Life had a solution to the problem, in the form of this one transistor set that was well within the construction abilities and budget of a Scout. The set shown here would run on two penlight cells with clear headphone volume for well over a thousand hours. And in a dire emergency, since the set consisted of a crystal detector with one-transistor audio amplifier, the article gave instructions on how to bypass the amplifier and simply use it as a crystal set with reduced volume.

The set is build on a board, with instructions to mount it in a cigar box (painted black, according to the directions), which left ample room for storing the antenna wire, ground lead, and headphones. Since the set was designed for CONELRAD use, the article instructed to find the local broadcast stations closest to 640 and 1240 on the dial, tune them in, and then mark the dial position for future emergency use.

The circuit calls for a FS2500A transistor, which is a general purpose NPN transistor, apparently manufactured by Bogue, also known Germanium Products Corporation. (See the substitution guide in the 1957 RCA Transistors and Semiconductor Diodes.)

The article was reprinted for a number of years in the Boys’ Life Radio and Signaling reprint booklet. Occasionally, the “Hobby Hows” column of Boys’ Life would answer a letter from a Scout asking where to find the plans for the receiver, who was directed to the reprint booklet. Therefore, I suspect more than a few scouts built one of these receivers, and I’m sure they were put to good use for entertainment purposes. The builders of these sets were undoubtedly the first kids on their block to own a transistor radio. Fortunately, none ever had to be used for the intended purpose of tuning in to CONELRAD alerts.

The author of the article was Howard G. McEntee, W2SI. McEntee was the author of the Radio Control Handbook, published by Gernsback Publications in 1955 and updated over the years.