Seventy years ago this month, the December 1954 issue of the British Radio Constructor noted that with “the festive season is drawing near, the reader may be interested in a simple little gadget which is guaranteed to liven up the party in more ways than one.” We’re sure that many of our readers might be similarly inclined.

Seventy years ago this month, the December 1954 issue of the British Radio Constructor noted that with “the festive season is drawing near, the reader may be interested in a simple little gadget which is guaranteed to liven up the party in more ways than one.” We’re sure that many of our readers might be similarly inclined.

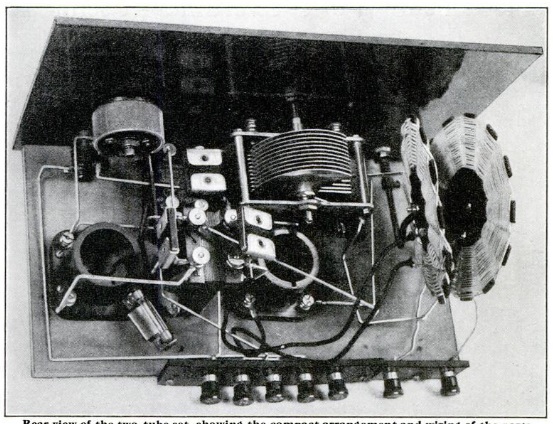

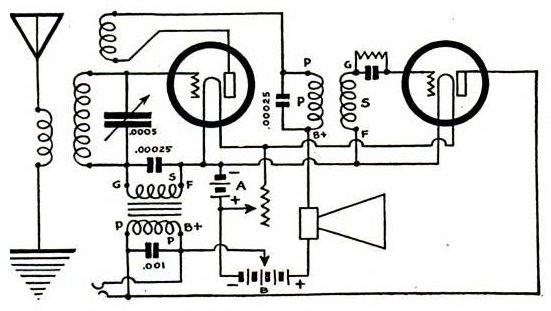

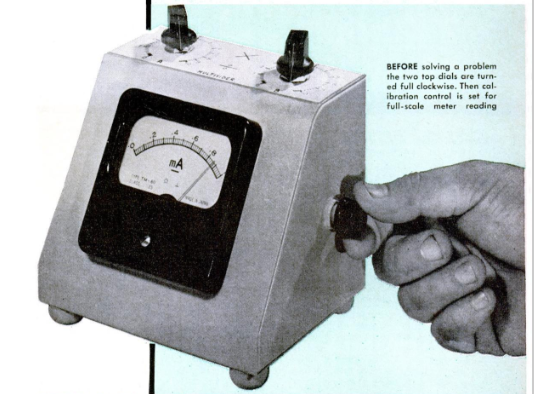

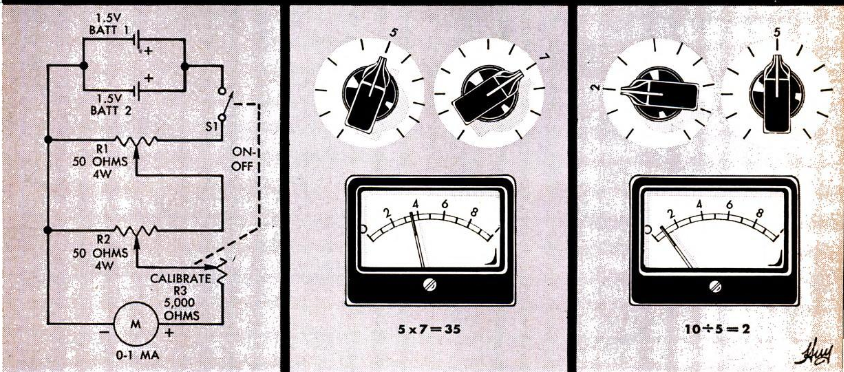

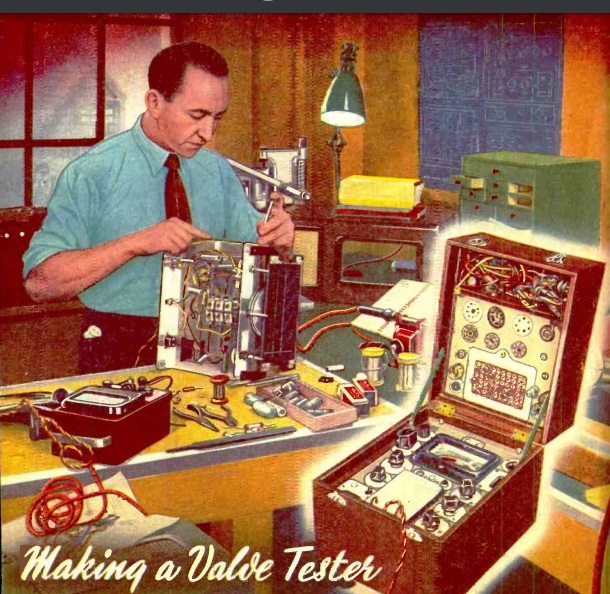

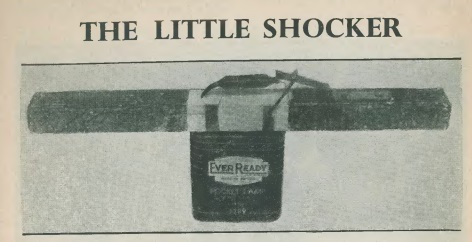

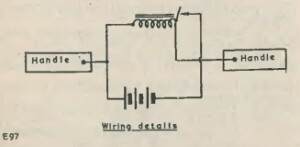

This device is self-explanatory. It’s similar to a homemade Ford spark coil. An autotransformer steps up the voltage of a battery, and the coil also serves to operate a crude relay to convert the voltage to DC. The two handles are formed from the foil from a candy bar glued over wood. When it’s switched on, it make an inviting buzzing sound, and you ask your friends to grab the handles.

This might make an interesting science fair project, although we suggest that you determine first whether the science teacher has a sense of humor. If not, another project might be better suited.

Also, even though the resulting current is very low, since some of that current will pass directly through the heart of your subject, we wonder if it might be dangerous in some cases. Therefore, if you’re going to make this project, we wonder if it might be better to make sure that both electrodes go to the same side of the body.

We should note that as a youngster, we independently invented a similar device, making use of an old filament transformer and a buzzer. No harm was caused to anyone.

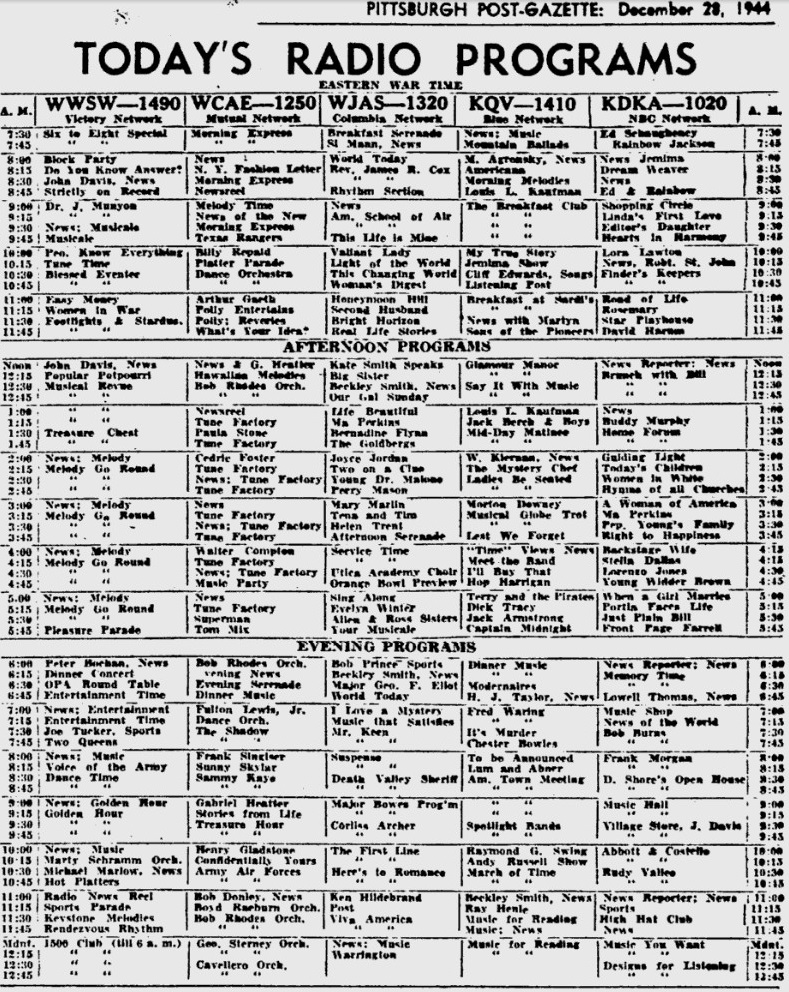

Here’s what was on the radio 80 years ago today, according to the radio listings in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Thursday, December 28, 1944.

Here’s what was on the radio 80 years ago today, according to the radio listings in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Thursday, December 28, 1944.