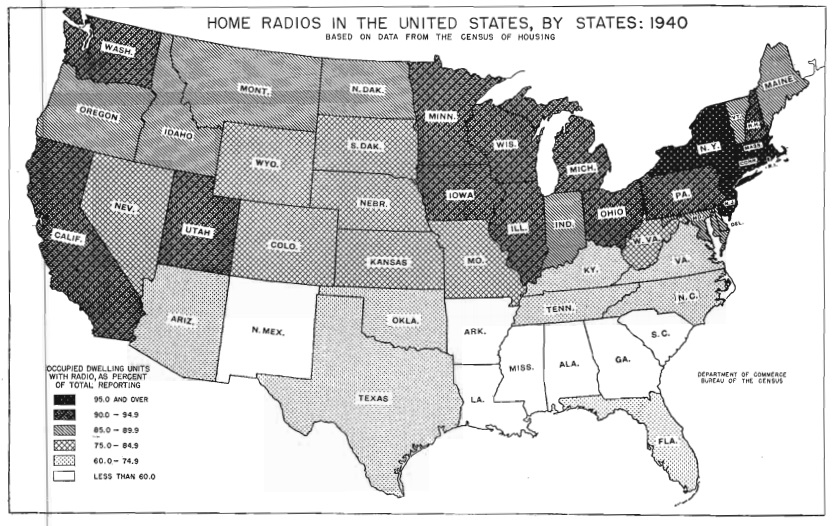

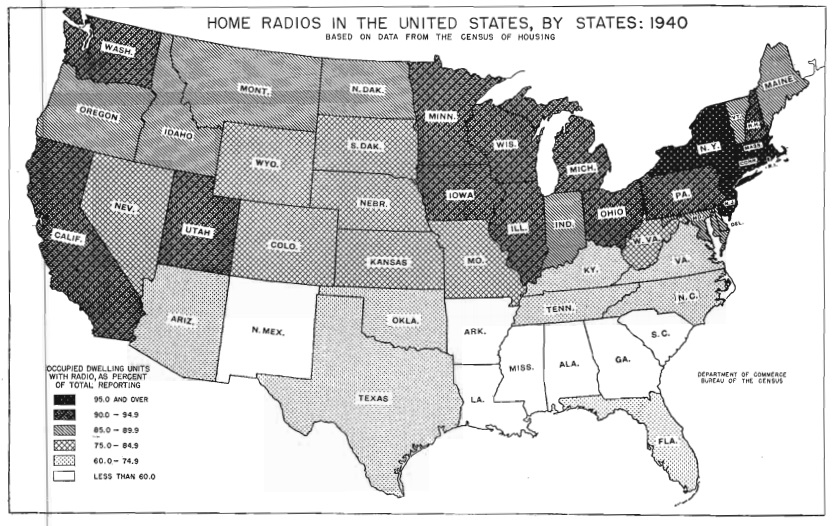

Seventy-five years ago today, the September 7, 1942, issue of Broadcasting magazine included a supplement with the radio figures from the 1940 census, as well as a complete log of all U.S. broadcast stations as of 1942, and figures showing the numbers of radio retailers and sales figures. The map above shows the percentage of radio homes in 1940. Since there was a freeze on new stations during the War, and since no new radios were being produced, the issue provides an interesting snapshot of radio in the United States during the War years.

Massachussetts led the nation with 96.2% of its homes being equipped with a radio. Within that state, the county with the highest percentage of radio households was Norfolk County, with 98.1% of the households having at least one radio. The last place honors went to the State of Mississippi, with only 39.9% of homes having a radio, despite twelve broadcasting stations in the state. Within that state, the county with the lowest percentage of radio households was Issaquana County, where only 320 households out of 1779 had a radio, or only 18%.

Of Minnesota’s 728,359 households, 664,296 had at least one radio, for a percentage of 91.2. Lake of the Woods County had the lowest penetration of radio receivers, with 1150 radio households out of 1501 total, for a percentage of 76.6%. Minneapolis and St. Paul had very high percentages of radio households, 96.6% and 96.7% respectively. They were edged out, however, by Rochester, with 96.8% of the households having a radio. The other city included in the listing of cities over 25,000 was Duluth, with 95.7% of the households having a radio.

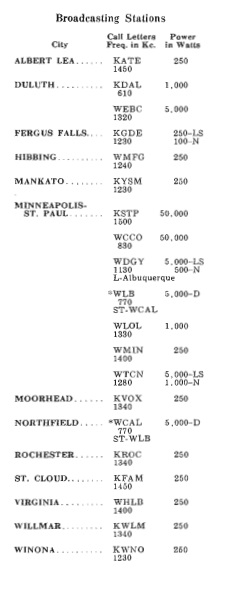

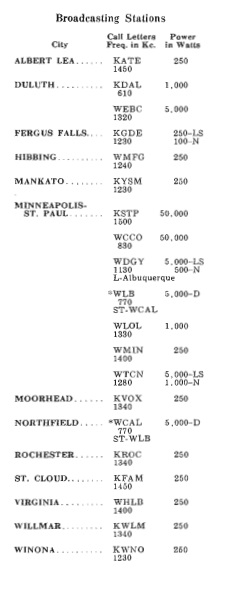

The station listing shown here reveals that during the War years, Minneapolis and St. Paul were served by seven stations. Both KSTP, 1500 kHz, and WCCO, 830 kHz, had 50,000 watt signals full time.

The station listing shown here reveals that during the War years, Minneapolis and St. Paul were served by seven stations. Both KSTP, 1500 kHz, and WCCO, 830 kHz, had 50,000 watt signals full time.

Three stations had 5000 watt signals during the daytime: WDGY on 1130 kHz, reduced its power to 500 watts at night, but the hours were determined by local time in Albuquerque, since it protected a station there. WLB, which later became KUOM, was daytime only, and also shared time on its 770 kHz frequency with WCAL in Northfield, an arrangement that continued in later decades. WTCN reduced its power on 1280 kHz to 1000 watts at night.

WLOL on 1330 kHz was licensed for 1000 watts, and WMIN ran 250 watts at 1400 kHz.

Duluth was listed as the home to KDAL on 610 kHz and WEBC on 1320 kHz. The other station serving the Twin Ports, WDSM, was licensed to Superior, Wisconsin, and appeared in the Wisconsin listings.

Cities with 250 watt stations included Albert Lea (KATE, 1450 kHz), Fergus Falls (KGDE, 1230 kHz, with 100 watts nighttime power), Mankato (KYSM, 1230), Moorhead (KVOX, 1340), Rochester (KROC, 1340), St. Cloud (KFAM, 1450), Virginia (WHLB, 1400), Willmar (KWLM, 1340), and Winona (KWNO, 1230).

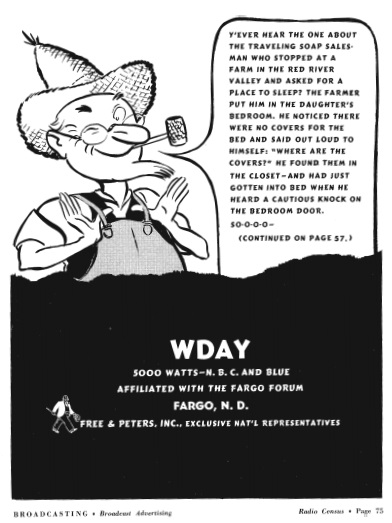

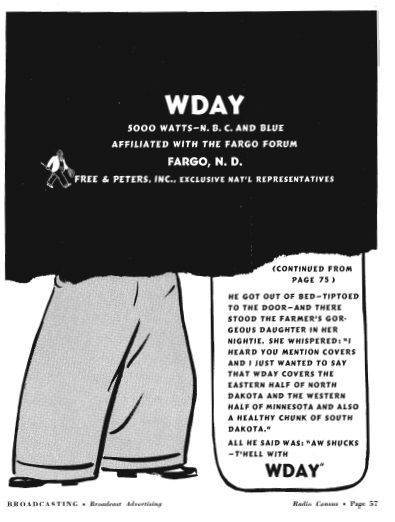

Another station covering Minnesota but not listed was WDAY in Fargo, which corrected the oversight by purchasing two full-page ads, one in the Minnesota listing and another in the North Dakota section, pointing out that it had a large service area in both states, and including a story, that must have seemed just a bit risque in 1942, about a traveling soap salesman and a farmer’s daughter.

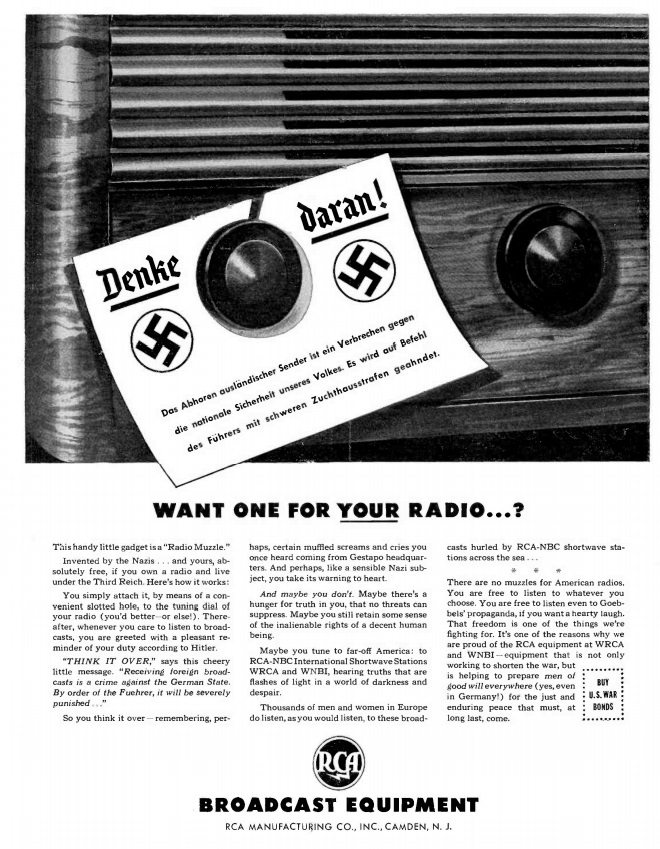

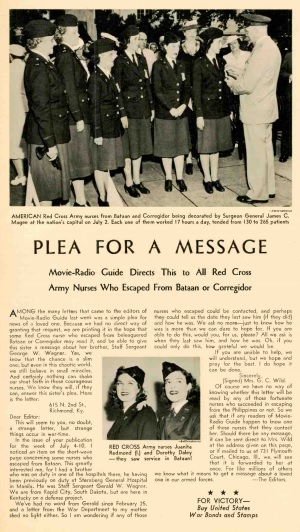

A few months after the fall of Corregidor, this letter appeared in the August 8, 1942, issue of Radio Guide.

A few months after the fall of Corregidor, this letter appeared in the August 8, 1942, issue of Radio Guide.

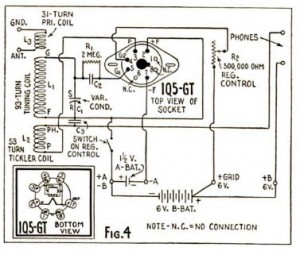

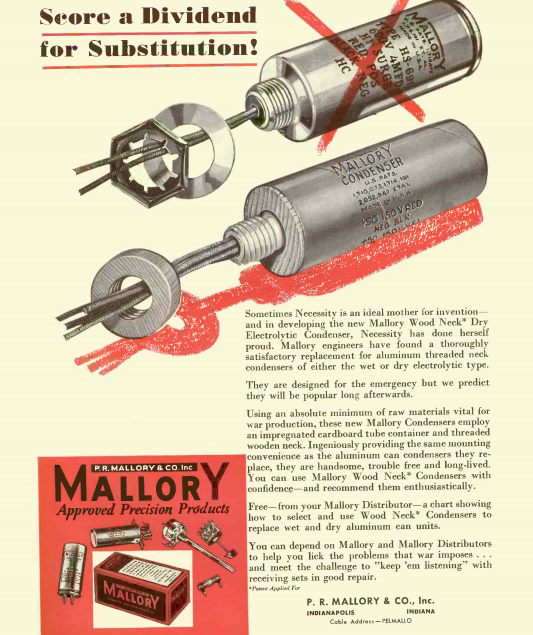

With wartime material shortages, replacement radio parts were hard to come by. And even when parts were available, the manufacturers had to adapt to wartime conditions.

With wartime material shortages, replacement radio parts were hard to come by. And even when parts were available, the manufacturers had to adapt to wartime conditions.