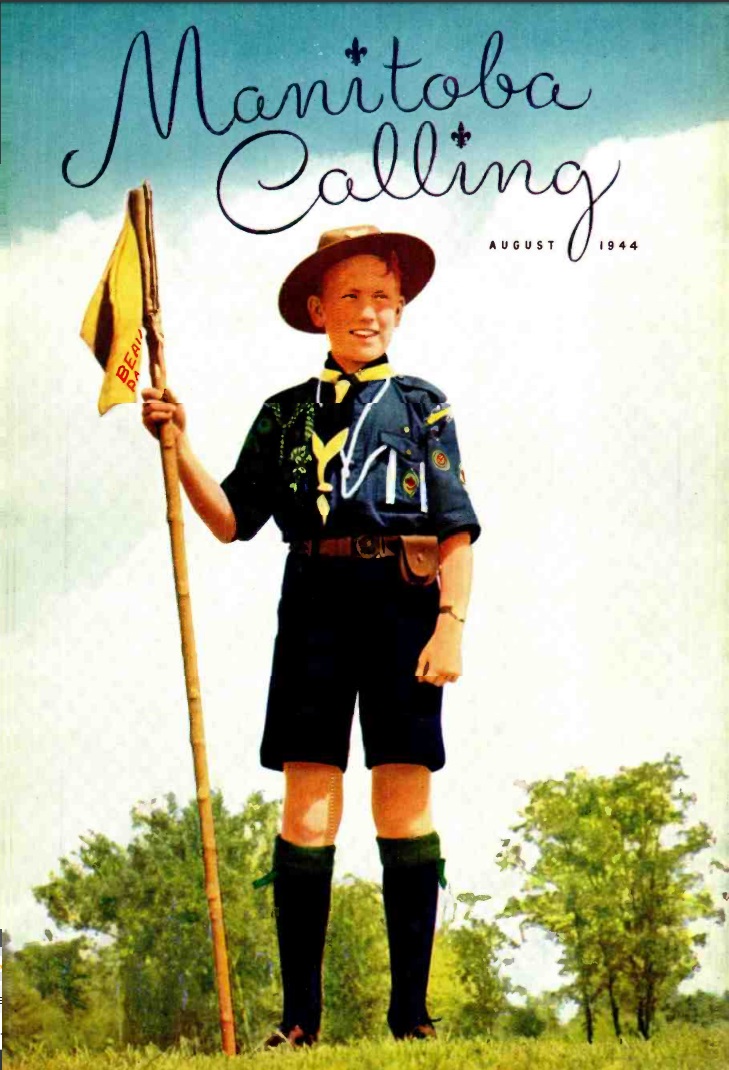

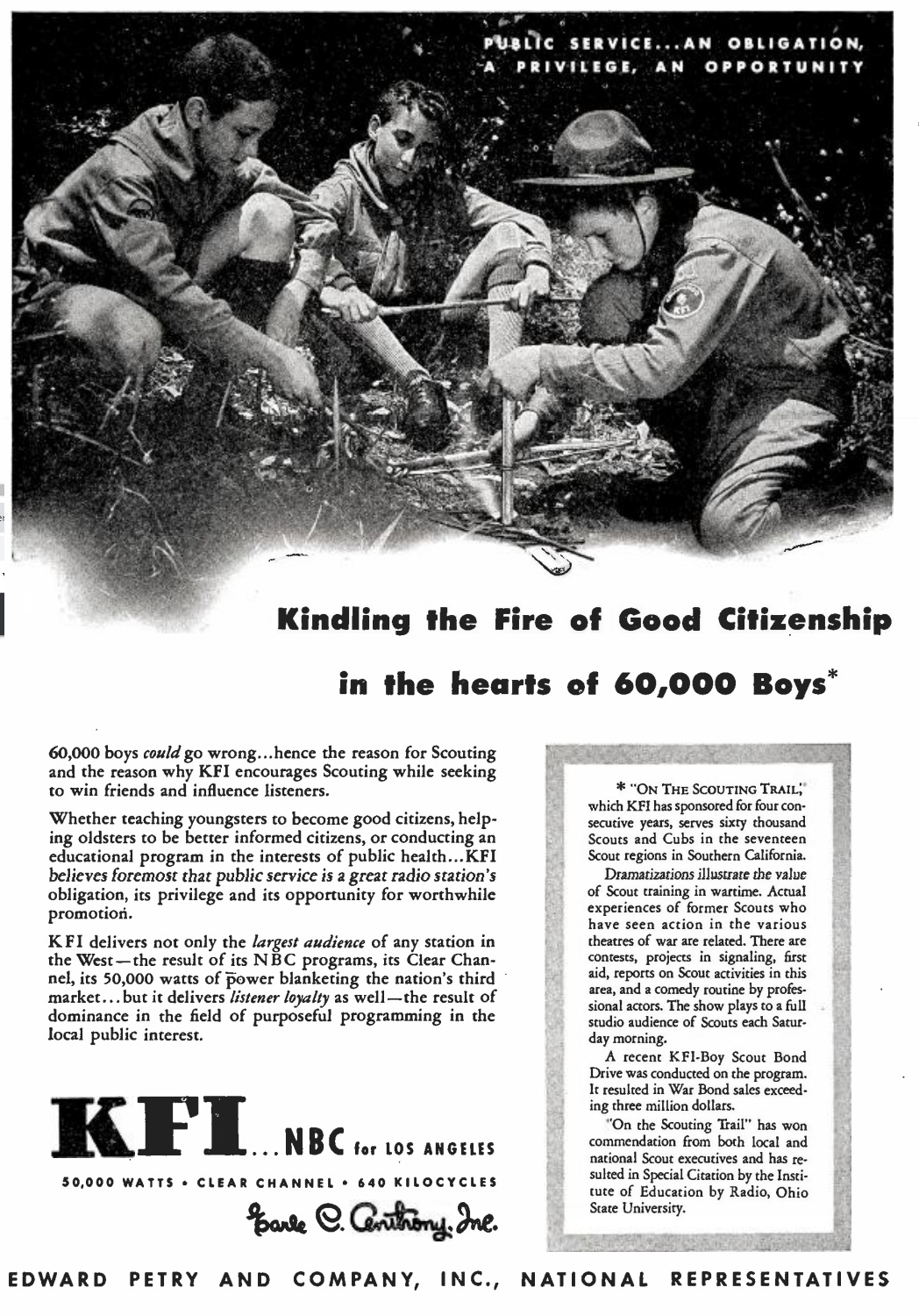

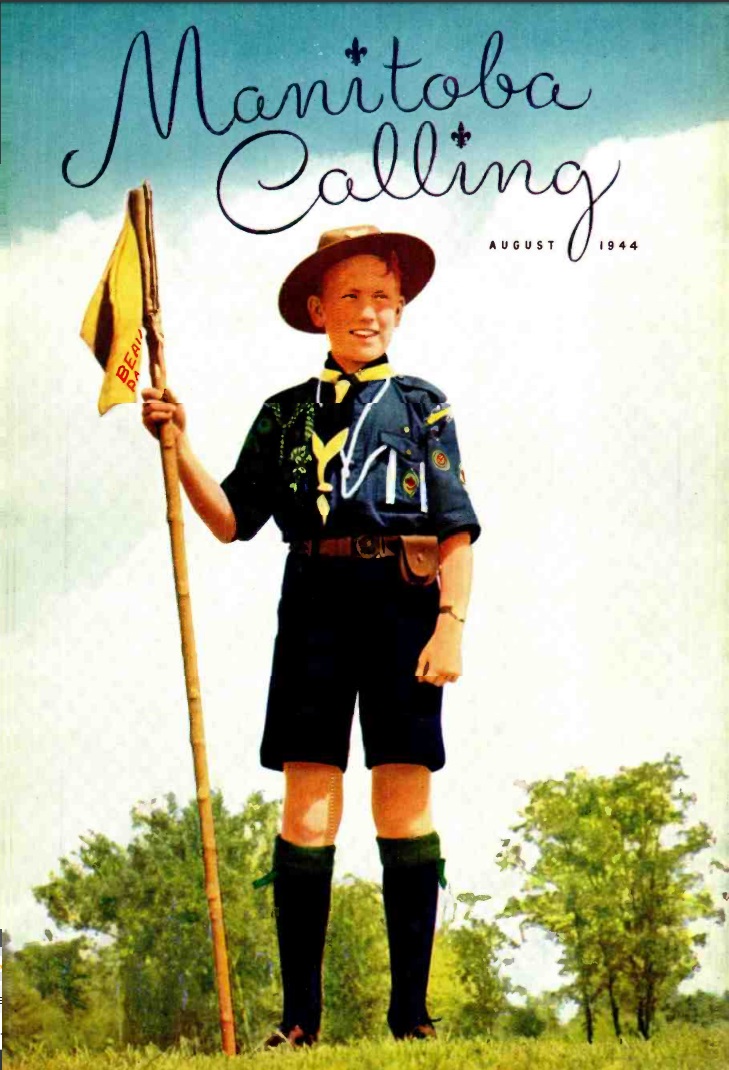

Shown here is Canadian Boy Scout Frank Lay, of the 67th Winnipeg (St. Aidan’s) Troop. He is featured on the cover of the August 1944 issue of Manitoba Calling, the monthly program guide of CKY Winnipeg, and sister station CKX in Brandon, Manitoba.

Shown here is Canadian Boy Scout Frank Lay, of the 67th Winnipeg (St. Aidan’s) Troop. He is featured on the cover of the August 1944 issue of Manitoba Calling, the monthly program guide of CKY Winnipeg, and sister station CKX in Brandon, Manitoba.

The entire issue of the magazine paid tribute to the value of Scout training for Citizenship. It noted that while scouting was designed as peace training, the organization had a fine record in its services to the war effort. At least 100,000 members of the Armed Forces had been Scouts. Indeed, of the 63 Victoria Crosses awarded to date, eight were won by former Scouts.

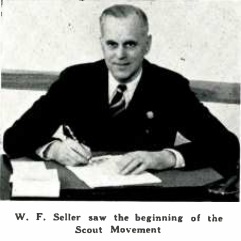

The magazine includes the reminiscences of W.F. “Bill” Seller, the manager of station CKX. The magazine calls him probably the veteran of all old Scouts in Canada, as he was a member of one of the earliest troops, in fact the first official troop formed in London. It noted that when Lord and Lady Baden-Powell visited Winnipeg in 1935, they met with Seller and exchanged reminiscenses of the early days of Scouting in England.

Here is the full text of Seller’s article:

Early Days in the Boy Scouts

By W. F. SELLER (Manager CKX)

Robert Baden-Powell at the first Scout encampment on Brownsea Island held in August 1907. Wikipedia image.

In August, 1907, two men, an orderly and 20 boys pitched tents and hoisted a Union Jack on Brownsea Island, near my home at Poole, Dorset, England. The leader of the party, General Baden-Powell with a friend (Major MacLaren), was making his first experiment in teaching English lads the scouting games he had learned himself as a boy and had used to such good advantage in South Africa, to test his idea of an organization for boys.

The twenty boys were gathered from several sources, from Eton and Harrow and from elementary schools; from the homes of the aristocracy and from the fisherman’s cottage. The troop was divided into four Patrols–each with a leader, Curlews – Ravens -Wolves -and Bulls. From morning till night they were busy learning to live in the open, to cook their own meals, to develop their powers of observation and above all to cultivate comradeship.

Canadian Scouts training for the Fireman’s badge, 1944.

Baden-Powell taught them how to follow trails, how to find a few grains of Indian corn in an acre of heather and how to hide and find messages in trees. Then, too, there were organized games and bathing and all the time these twenty boys were unconsciously acquiring habits of self control, fair play and manliness; in other words, the underlying principles of the Boy Scout Movement. The evenings were topped off with the group gathering round the campfire listening to thrilling stories, bird calls, lessons on stalking and singing, all led by “The Chief “.

By the end of two weeks Baden-Powell had proved that his scheme was sound to the core and he settled down to launch it upon the world. Its value was soon realized, the movement grew and Baden-Powell not only became a hero to but beloved by boys throughout the world.

It was not my good fortune to be in on the experimental camp but a cousin of mine was and his glowing accounts of Baden-Powell and his ideas fired a small group of us with enthusiasm, so in 1908 after purchasing one of the first issues of “Scouting for Boys“, we decided to become Boy Scouts. There was no local organization, we just got together, ten of us, using a shack at the bottom of the garden for our “club house “. We met Thursday nights and Saturday afternoons. There were no uniforms at first and then we were able to buy Scout supplies and started to become real Scouts. This, too, was tough, it was all so new.

It was not my good fortune to be in on the experimental camp but a cousin of mine was and his glowing accounts of Baden-Powell and his ideas fired a small group of us with enthusiasm, so in 1908 after purchasing one of the first issues of “Scouting for Boys“, we decided to become Boy Scouts. There was no local organization, we just got together, ten of us, using a shack at the bottom of the garden for our “club house “. We met Thursday nights and Saturday afternoons. There were no uniforms at first and then we were able to buy Scout supplies and started to become real Scouts. This, too, was tough, it was all so new.

For the first few weeks after getting our shorts, shirts, hats and shoes, etc., we used to carry the stuff up to the woods, change under the rhododendron bushes, practise our scouting and then in native’s dressing rooms change back again and amble off home.

After a while we decided that this would not do: if we were going to be Scouts we should be proud of the fact, and so we went one step farther and we changed into uniform in the shack and all marched in patrol formation to our scouting practises. For a time we had to take the public taunts of other boys whose ideas of sport were not always satisfied with wordy insults, but were backed up with sticks, stones and sometimes eggs!

Paying Their Way

Soon, however, we had two patrols of ten each and we looked for a scoutmaster and rented accommodation in one of the schools. To pay the rent, we each donated a few coppers each week to the club funds. If one could afford six -pence o.k., if only a penny, again o.k. But often when rent day came around funds were inadequate, so instead of “scouting” on the Saturday afternoon, we would all go out and hunt up odd jobs, running errands, digging gardens, cutting lawns, etc. Everyone brought in whatever he had earned to the common funds and it worked. Came the day when we had three patrols and could officially qualify as a “troop “. We applied for a Charter and Troop Flag, which was presented to us at a special ceremony at Canford Manor by Lady Wimborne and so we became the first troop of Boy Scouts in the world, registered as the 1st Parkstone Troop, afterward Lady Baden Powell’s own. We attended the first scout rally which was held at the Crystal Palace, London. 15,000 I believe were present, and we were impressed by the size of the old Crystal Palace, when due to rain the march past was held entirely under glass. The following year we attended the rally at Windsor Castle and later one at Birmingham. This last, numbering close to 200,000, was made most interesting for us by the presence in our troop of a prince of the royal house of Ethiopia, dressed in his native costume, one of the sons of Haille Selassi. The lad, about 13, had stowed away on a liner leaving his country for Great Britain and had to remain in England until dignataries from Ethiopia could arrive and return with him in befitting splendour. He was sent to our home town and in despair the gentleman responsible for his care asked our troop to share the responsibility and many were the interesting episodes provided by this young man.

I believe the troop justified its membership in the great brotherhood of scoutdom. Our ambulance patrol was on duty at most public functions and a sports gathering including the first flying meet ever held. This was at Bournemouth, and during this meet the pioneer A. V. Rowe was killed in a vol-planing competition. [Louis] Bleriot, the first man to fly the English Channel, was there and we also saw [Hubert] Latham flying one of the first monoplanes, a crazy looking contraption with the appearance of an over -developed kite. We had the first King’s Scouts and the first Silver Wolf; won many district and national trophies, and had a good time doing it, with clean keen competition and the joy of contest rather than conquest being strongly stressed.

I believe the troop justified its membership in the great brotherhood of scoutdom. Our ambulance patrol was on duty at most public functions and a sports gathering including the first flying meet ever held. This was at Bournemouth, and during this meet the pioneer A. V. Rowe was killed in a vol-planing competition. [Louis] Bleriot, the first man to fly the English Channel, was there and we also saw [Hubert] Latham flying one of the first monoplanes, a crazy looking contraption with the appearance of an over -developed kite. We had the first King’s Scouts and the first Silver Wolf; won many district and national trophies, and had a good time doing it, with clean keen competition and the joy of contest rather than conquest being strongly stressed.

I could ramble on like all pioneers, to tell you of the time when camping, the troop saved a group of cottages from destruction by forest fire, the time a boat -load of us were nearly drowned but for the timely rescue of the Coast Guards, the course of home nursing undertaken by some of the boys, the concerts we ran, the bazaars we organized to rase our own funds.

“B.P.’s” Marriage

I could tell how we got news of Baden-Powell’s wedding at St. Peter’s Church, Parkstone, and were able to turn out in time to salute him and his bride.

We were very fortunate that Baden – Powell had selected our district for his experiment and that he chose a lady from our home town for his bride, for as a result, we enjoyed many informal visits and interesting evenings at our club rooms with the Chief himself. Many members of that first troop of Scouts are living in Canada and most of that same troop served in the first World War. We all carry pleasant memories of the wonderful experiences we had as Scouts and one of my prized possessions is the old Scout shirt resplendent with badges, all-round cords and service stars, together with the scarf and many pictures that are now historical but unfortunately not good enough for reproduction.

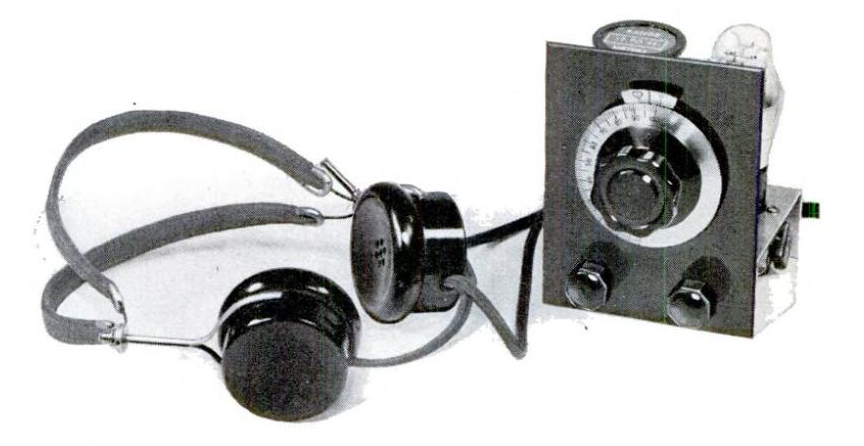

If you had put together this minimalist little shortwave set when it was published in Popular Science in August 1939, you would have been able to use it to pull in the news of the beginning of World War II the next month.

If you had put together this minimalist little shortwave set when it was published in Popular Science in August 1939, you would have been able to use it to pull in the news of the beginning of World War II the next month.