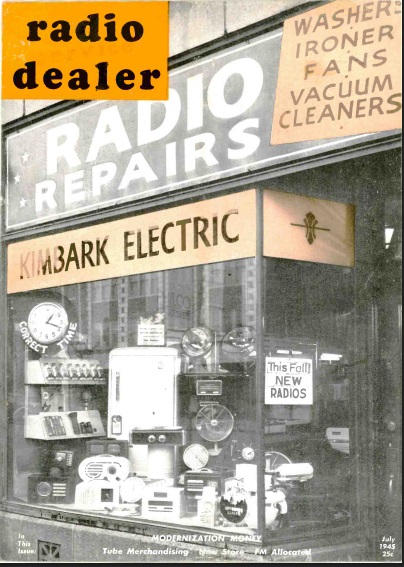

Eighty years ago, there was still a war going on, but people were itching for things to get back to normal. For example, civilian radios were still out of production, but this dealer guessed (correctly, it turns out) that there would be new ones rolling off the assembly line come fall. The picture appears on the cover of the July 1945 issue of Radio Service Dealer, and that issue gives no clues as to exactly where the sign is located.

Eighty years ago, there was still a war going on, but people were itching for things to get back to normal. For example, civilian radios were still out of production, but this dealer guessed (correctly, it turns out) that there would be new ones rolling off the assembly line come fall. The picture appears on the cover of the July 1945 issue of Radio Service Dealer, and that issue gives no clues as to exactly where the sign is located.

But with a little bit of detective work, we found the location, and we also determined that the picture shown above was Photoshopped! The sign above reads “This Fall! New Radios.” The magazine doesn’t say where the sign is located. The magazine states only “dealer looks forward.”

But the identical photo appeared in the December 1943 issue of the magazine. Well, we should say that it was almost identical. Because the sign really said, “Wanted-Used Radios.” I bet they still wanted them in 1945, but a graphic artist (if not the dealer) guessed that the end of the shortage was in sight.

The 1943 issue reveals that the shop was Kimbark Electric Appliance Co., 1309 E. 53rd St., Chicago. The owner was Harold E. Wollenhaupt, who died in 1989.