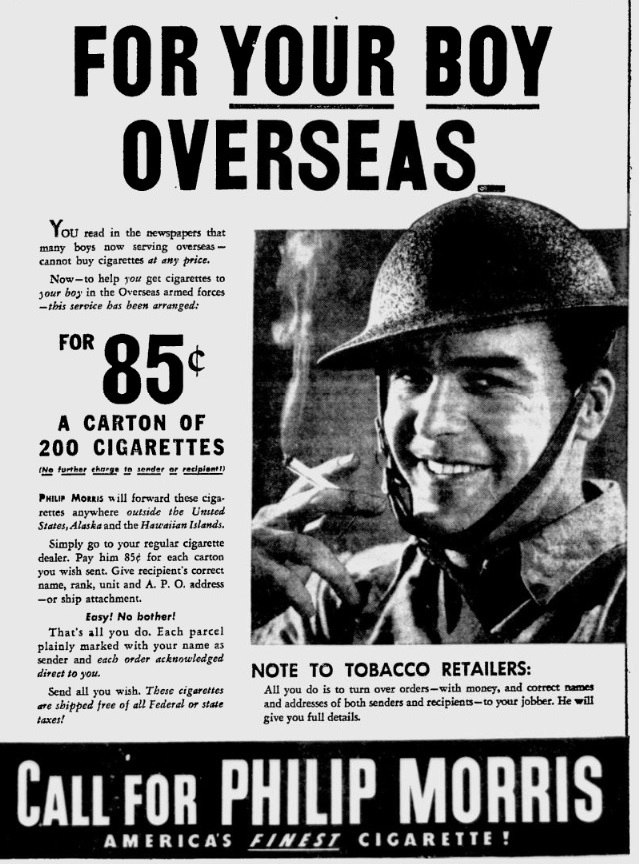

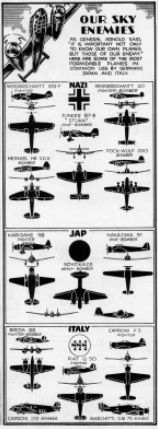

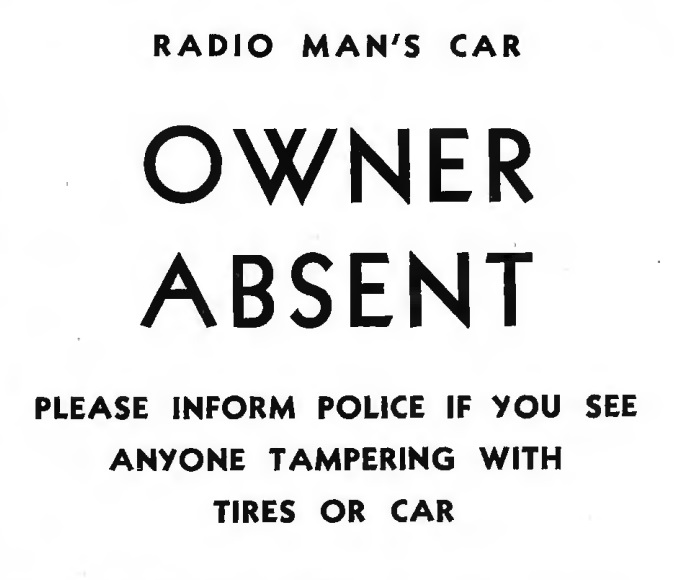

As a public service, we present the image above. You can print it, and when your car is parked, you can display it, facing out, on the passenger side of your car. The idea is not ours. In fact, it originally appeared 80 years ago this month in the May 1942 issue of Radio Retailing.

As a public service, we present the image above. You can print it, and when your car is parked, you can display it, facing out, on the passenger side of your car. The idea is not ours. In fact, it originally appeared 80 years ago this month in the May 1942 issue of Radio Retailing.

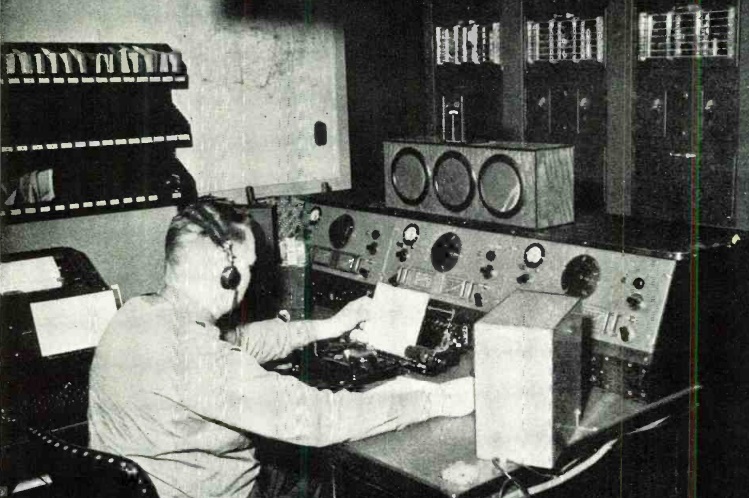

Many radio men had written to the magazine lamenting the fact that even though theirs was a vital profession, they didn’t have any special priorities when it came to tires or gasoline. So when they went on a service call, their car parked out on the street was a sitting duck for thieves who could steal the spare tire. In some cases, the thieves were brazen enough as to jack up the car and steal the tires, wheels and all.

Several Western salesmen had come up with the idea of the sign shown here. It would alert passers by that the owner was absent, and anyone tampering with it was unauthorized. According to the magazine, the mere presence of such a sign would in many cases scare off the thieves from making an attempt. The magazine didn’t say so, but, of course, we doubt that any thief would dare target a car after learning that the owner was a radio man. We have no doubt that it would have the same effect today.