The first automatic amateur radio repeater station was put on the air in 1956 by Art Gentry, W6MEP, and it’s been on the air ever since. But you can see that the idea had been around for a while, as shown in this article 80 years ago, in the June 1945 issue of QST.

The first automatic amateur radio repeater station was put on the air in 1956 by Art Gentry, W6MEP, and it’s been on the air ever since. But you can see that the idea had been around for a while, as shown in this article 80 years ago, in the June 1945 issue of QST.

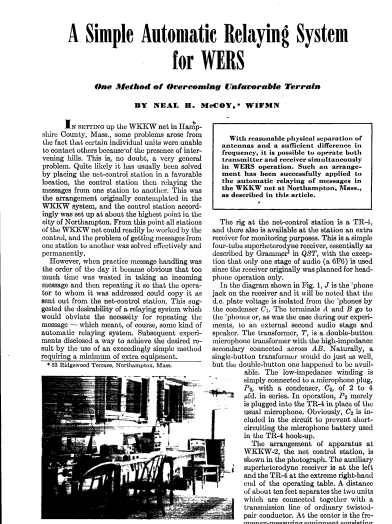

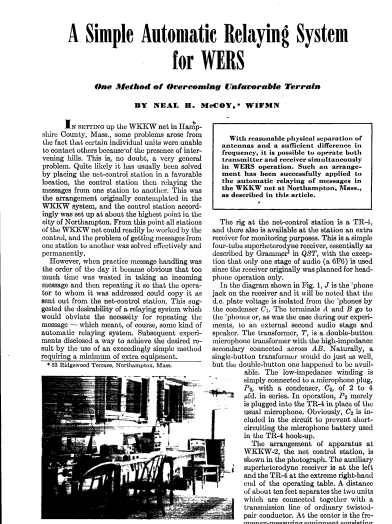

At the time, Amateur Radio was still off the air for the duration of the war, but some hams involved in civilian defense activities did have authorization to operate as part of the War Emergency Radio Service (WERS), usually on the 2-1/2 meter band. One such WERS station was WKKW in Hanipshire County, Mass. The network was headed up by a net control station (NCS) at one of the highest points in the county, which ensured good coverage. The problem was, however, that not all stations could hear each other. So if a message needed to be relayed, it meant an added step of the NCS relaying it.

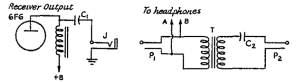

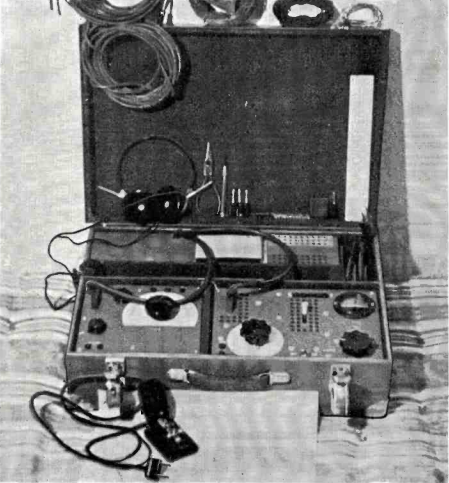

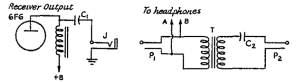

The solution was an automatic relaying system at the NCS station. While the article called it “automatic,” it did not automatically hit the air as with a more modern repeater. Instead, the NCS merely patched the audio from a second receiver into the transmitter, with the patch cord shown here. He monitored through headphones, and switched back when the message was over. Of course, the transmitter and receiver had to be on different frequencies, so when a message had to be retransmitted, the originating station was told to QSY to 112.7 MHz, and the repeated signal was on the net frequency of 114.6 MHz.

The solution was an automatic relaying system at the NCS station. While the article called it “automatic,” it did not automatically hit the air as with a more modern repeater. Instead, the NCS merely patched the audio from a second receiver into the transmitter, with the patch cord shown here. He monitored through headphones, and switched back when the message was over. Of course, the transmitter and receiver had to be on different frequencies, so when a message had to be retransmitted, the originating station was told to QSY to 112.7 MHz, and the repeated signal was on the net frequency of 114.6 MHz.

The equipment had to be reasonably well shielded, and the antennas had to be separated. (The article noted that the feed line was a twisted pair.) The article concluded by noting, “it is to be hoped that others will experiment with this and other simple means of relaying, since it is an interesting field of experimentation and one which offers a good return in the way of improved WERS operation. It suggests, also, interesting possibilities for postwar amateur activities at the high frequencies.”

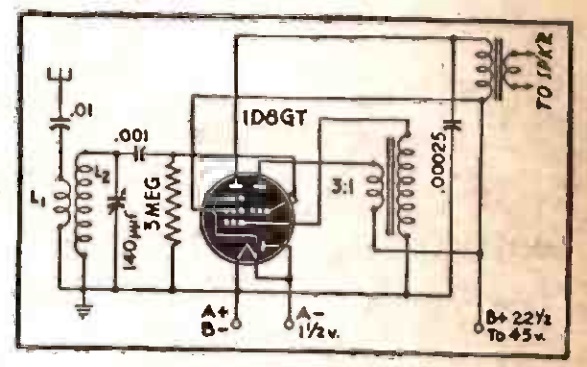

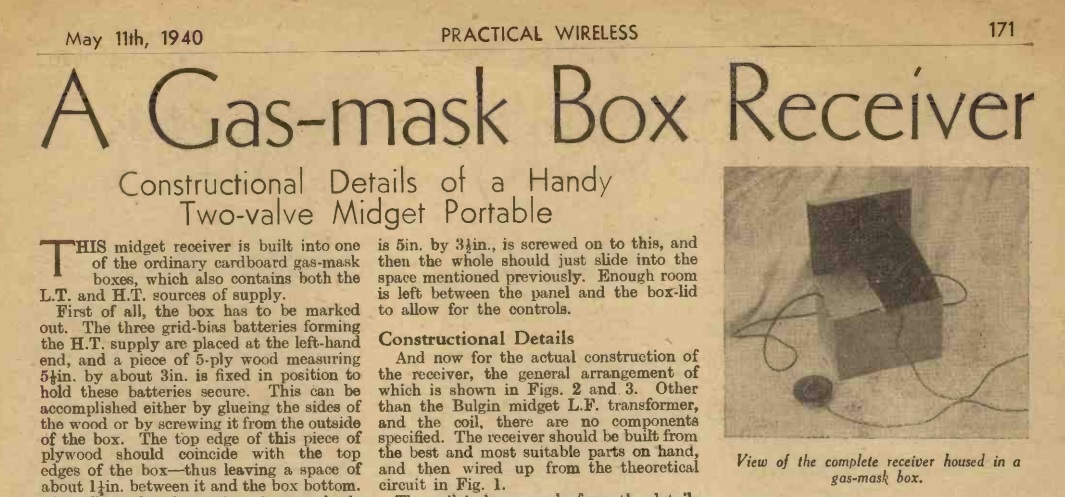

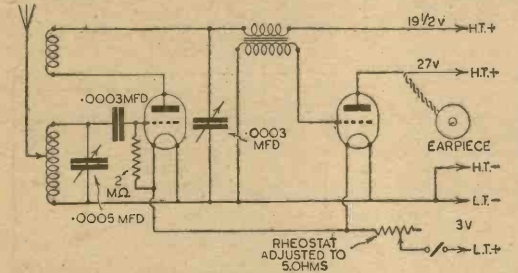

Eighty-five years ago this month, the June 1940 issue of Practical Wireless showed how to put together this basic crystal set for the beginning radio experimenter. Just because there was a war going on didn’t mean that one couldn’t get a start in radio with this simple receiver.

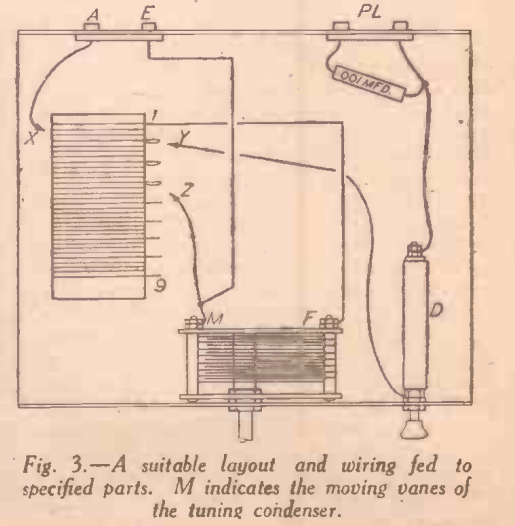

Eighty-five years ago this month, the June 1940 issue of Practical Wireless showed how to put together this basic crystal set for the beginning radio experimenter. Just because there was a war going on didn’t mean that one couldn’t get a start in radio with this simple receiver. It noted that buying commercial coils would be an easy way to make a compact set. But it encouraged winding your own, as that way, the beginner would be able to see the works.

It noted that buying commercial coils would be an easy way to make a compact set. But it encouraged winding your own, as that way, the beginner would be able to see the works.