A hundred years ago today, November 17, 1915, the United States fought the Battle of Fort Rivière. Chances are, most Americans have never heard of this battle, even though it resulted in three Medals of Honor being awarded to U.S. marines or sailors.

Among the Medal of Honor recipients was then-Major, later General Smedley Darlington Butler, who led the U.S. forces in the battle, which was part of the U.S. occupation of Haiti, which had begun on July 28, 1915. The occupation had been motivated by two factors. Those factors overlap a great deal, and historians have debated the relative importance of each. First of all, there was a need to protect U.S. commercial interests in Haiti. The country had potential with agriculture, minerals, and ports. American interests were hampered by, among other things, the fact that foreigners were not allowed to own property.

The other concern was German influence in the Western Hemisphere, and the United States viewed Germany as having too much influence in Haiti. While the German population was quite small, it did have a very great commercial influence, since a very large portion of the commercial activity was controlled by German families with strong ties to the old country. Also, the Germans were more willing to marry in to prominent Mulatto families, thus skirting the property ownership laws.

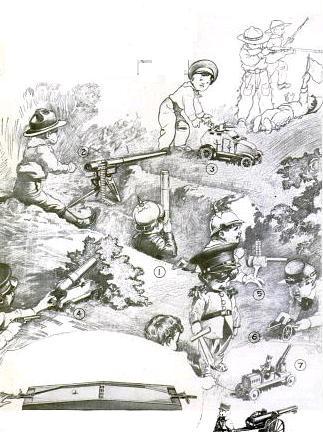

President Wilson sent in the marines in July, and the largest battle took place on November 17 as U.S. sailors and marines stormed an old French fort where the peasant rebels were holed up. The battle against the poorly equipped rebels was over quickly. Over 50 rebels were killed. The only U.S. casualty was a marine who had two teeth knocked out by a rock thrown at him by one of the rebels. While a few later skirmishes took place, this was the decisive battle.

Under the occupation, Haiti adopted a new constitution written by then-Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. It gave U.S. officials more or less absolute veto power over acts of the Haitian government, and also guaranteed foreigners the right to own property.

The occupation did have the result of modernizing Haiti. For example, Port-au-Prince became the first location in the Caribbean to have an automated dial telephone system. Also, Haiti had radio broadcasting as early as 1926, as reported in the February 26, 1927, issue of Radio World.

General Smedley Butler

As a result of the battle, Butler received the first of his two Medals of Honor, and he went on to become, at the time, the nation’s most decorated military hero, and made a name for himself two other times off the battlefield.

The first was in in 1934 when he testified before the House Special Committee on Un-American Activities, revealing what came to be known as the “Business Plot.”

He testified that he had been called upon by business leaders to lead a march of veterans on Washington, at which point he would stage a coup against President Roosevelt. Roosevelt would be kept on as a puppet figure, with Butler wielding most of the power. Butler had been a key figure in earlier marches by veterans, was respected as a military leader, and the conspirators, most of whose names were never publicly revealed, planned to use Butler as their puppet, so he testified.

The Committee, and the American press, generally dismissed Butler’s testimony as an implausible conspiracy theory. The phrase “tinfoil hat” hadn’t yet been coined, but if it had, it probably would have been applied to Butler. Compounding the problem was that Butler seemingly hadn’t named any names, although this wasn’t entirely true. He had named names, but since most of his allegations amounted to hearsay, the Committee had refused to make them public.

The most plausible explanation, it seems to me, is that there was indeed a conspiracy to overthrow the government, and that Butler was approached to lead it. It doesn’t appear that he had any motive to fabricate the story. However, it also seems likely to me that the conspiracy wasn’t as large as he was led to believe by those who approached him.

In 1935, based upon his experiences as a career military officer, Butler published “War is a Racket,” a widely-distributed pamphlet in which he argues that war is, indeed, a racket, which he summarized as follows:

War is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives. A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of the people. Only a small ‘inside’ group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many. Out of war a few people make huge fortunes.

Butler’s recommendation was to make war unprofitable by conscripting soldiers only after conscripting capital. Of course, the naysayers would say that this runs roughshod over private property which, of course, it does. But conscription of soldiers also runs roughshod over their own personal liberties, so the idea doesn’t strike me as too farfetched. Butler also recommended that the declaration of war be done not by congress, but by a referendum of those subject to service, and also a restriction of the military to self-defense only.

The book is available online at numerous places, including archive.org.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

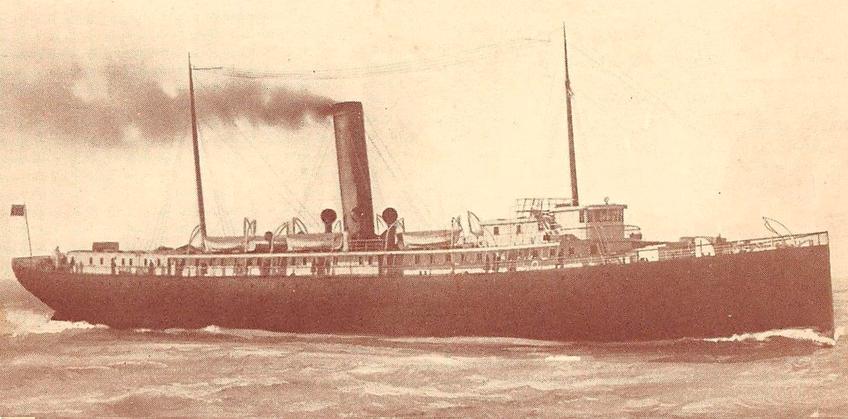

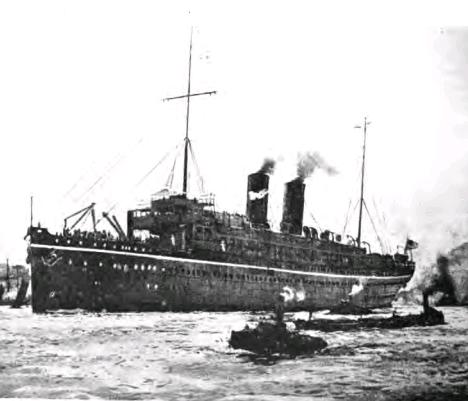

Among the dead was Marconi wireless operator George Henry Dewey, shown here. After finishing his education, he had initially entered the post office as a telegrapher and clerk, and then studied at the British School of Telegraphy and entered the service of the Marconi company. In his short career, he had served aboard five other ships before his appointment to his position aboard the Persia.

Among the dead was Marconi wireless operator George Henry Dewey, shown here. After finishing his education, he had initially entered the post office as a telegrapher and clerk, and then studied at the British School of Telegraphy and entered the service of the Marconi company. In his short career, he had served aboard five other ships before his appointment to his position aboard the Persia.

![]()