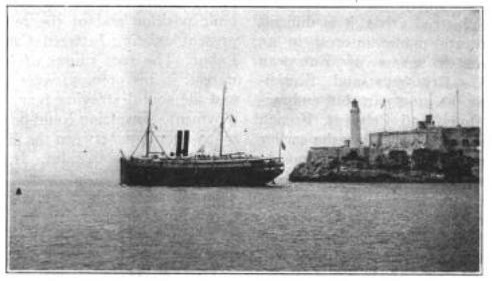

A hundred years ago this month, the December 1915 issue of Wireless Age carried an interesting account of J.K. Noble, the wireless operator aboard the steamer Seguranca, recounting the ship’s voyage from Pensacola to London with a cargo of naval stores and lumber. The ship left New York en route to Pensacola on May 30, and the most remarkable incident on that leg of the voyage was a hawk which perched itself on the ship’s mast looking for a meal. It set its eyes on the ship’s mascot, a kitten named Booze, and finally swooped down on the cat. The cat fought back and managed to break free. The ship’s crew attempted to shoot the hawk, but the bullet went wild and the bird flew away.

The trip across the Atlantic was initially uneventful. Noble points out that the wireless gave the latest news every night from Cape Cod and Poldhu, England. He was able to copy the French war news from FL, the Eiffel Tower station, up to 1600 miles from Paris. The French time signals were also used to check the accuracy of the ship’s chronometer.

As the ship neared England, the traffic picked up, the call signs were unfamiliar, and almost all messages were coded. The call signs he heard included ZAAW, ABMV, CX, A27, 51M, XXJ, and YCF.

On July 7, Noble copied a message sent by the Poldhu station to the Saxonia, then serving as a troop ship, with a warning of a possible bomb placed on board by a fanatic who had attacked J.P. Morgan (apparently Erich Muenter).

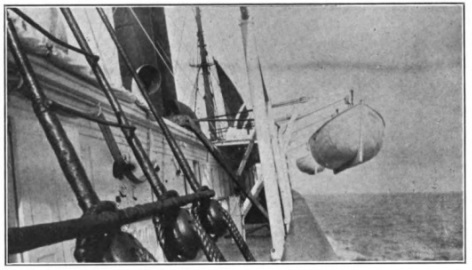

As the ship entered the war zone, the Seguranca kept her neutral American flag illuminated at night, as well as the letters “U.S.A.” which had been painted on both sides of the ship. The lifeboats were slung out. Two submarines were sighted, but they kept a considerable distance.

The ship entered the English Channel through the Strait of Dover, passing through two light ships. The British ordered the Seguranca to take down her aerial at this point. At Deal, the ship was stopped by a British patrol boat and its officers examined the Seguranca’s papers. After a few hours’ delay, a pilot boarded and the ship headed to London under torpedo boat escort.

The big guns in France could be heard, the sound ceasing only as the ship started up the Thames. To guard against air raids, the ship’s lights had to be covered at night, and the generator had been ordered shut off at 10:00 PM.

Because of a wartime shortage of stevedores, the ship remained in London for five and a half weeks while being unloaded. While in London, Noble was stopped more than one time by British officers trying to persuade him to enlist in the British forces.

The return trip gave Noble the opportunity to hear more radio traffic. After passing Dover, the aerial was reinstalled, and Noble was back on the air. On August 19, he first copied the Baron Erskine (MHF) reporting that it was being chased by a sub. One of the patrol boats reported that it was coming to her assistance. At 2:45, he copied an SOS, stating that it had been struck by two enemy subs. This ship gave a location, but didn’t sign a call sign. Noble concluded that this SOS had come from either the Arabic or the Nicosion. Since the reported location was 200 miles away, the Saguranca did not go to the aid of the distressed vessel.

Soon thereafter, at 5:30, he copied an SOS from the steamer Bovic, call sign GDO, reporting that she was being chased by a sub. A patrol boat said that she was coming to the Bovic‘s aid, but at 7:30, the Bovic reported that she was sinking. The patrol boat reported that she would be there by 9:00.

Two days later, the steamer Georgia (call sign GDT) was requesting a doctor, since her chief engineer had seriously wounded himself with a rifle. The Minnehaha, MMA, had a doctor aboard, but had some doubts as to the veracity of the message, fearing that it might have been faked by the Germans. After some confirmation, a rendezvous was arranged, and an hour or two later, the Minnehaha reported that the wounded man was on board.

The remainder of the voyage back to New York was uneventful, and the “Seguranca steamed past the lights of Coney Island and headed up the bay while on the lips of those on board was framed a word full of meaning–home.”

According to the Nautical Gazette, the Seguranca was launched in 1890 and served until 1920.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()