On hundred years ago today, April 2, 1917, President Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress and asked for a declaration of war against Germany.

In his address, Wilson first told the assembled Congress that there were “serious, very serious, choices of policy to be made, and made immediately.” He first cited the German government’s declaration on February 3 or unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, which he called “a warfare against mankind.”

It was clear that Wilson saw the role of the United States as a superpower who would win the war through overwhelming national power:

What this will involve is clear. It will involve the utmost practicable cooperation in counsel and action with the governments now at war with Germany, and, as incident to that, the extension to those governments of the most liberal financial credits, in order that our resources may so far as possible be added to theirs. It will involve the organization and mobilization of all the material resources of the country to supply the materials of war and serve the incidental needs of the nation in the most abundant and yet the most economical and efficient way possible. It will involve the immediate full equipment of the Navy in all respects but particularly in supplying it with the best means of dealing with the enemy’s submarines. It will involve the immediate addition to the armed forces of the United States already provided for by law in case of war at least 500,000 men, who should, in my opinion, be chosen upon the principle of universal liability to service, and also the authorization of subsequent additional increments of equal force so soon as they may be needed and can be handled in training. It will involve also, of course, the granting of adequate credits to the Government, sustained, I hope, so far as they can equitably be sustained by the present generation, by well conceived taxation.

And while Wilson stated that the United States had no quarrel with the German people, it’s government, as evidenced by the Zimmermann telegram, was evidence of “criminal intrigues everywhere affot against our national unity: ” That it means to stir up enemies against us at our very doors the intercepted note to the German Minister at Mexico City is eloquent evidence.”

The country would be at war within four days. The Senate approved the declaration of war on April 4, with the House approving it on April 6.

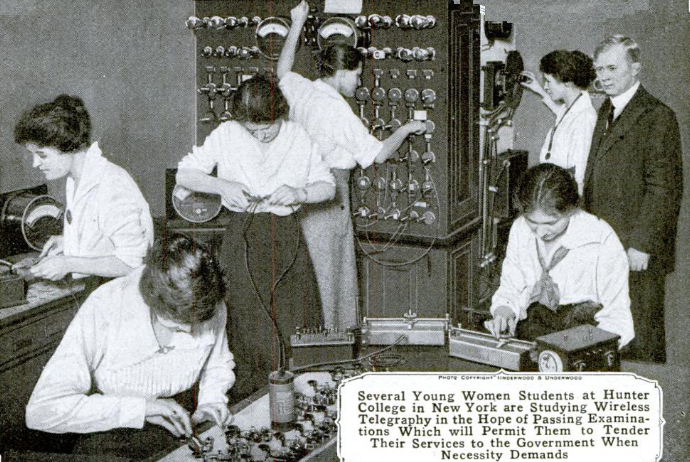

A hundred years ago this month, the May 1917 issue of Popular Mechanics showed this image of woman students at Hunter College, New York. The women were looking forward to the possibility of wartime labor shortages that would allow them to serve the government as wireless operators.

A hundred years ago this month, the May 1917 issue of Popular Mechanics showed this image of woman students at Hunter College, New York. The women were looking forward to the possibility of wartime labor shortages that would allow them to serve the government as wireless operators.