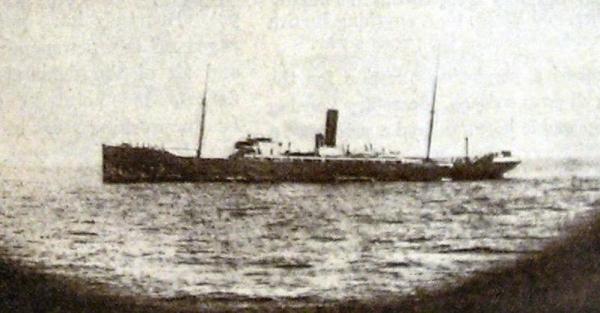

Commerce raider SMS Möve. Wikipedia photo.

A hundred years ago today, the October 16, 1917, edition of the Chicago Tribune carried the story of Walter Smith of Norway, Connecticut. Earlier in the year, Smith, who had worked as a brakeman on the New Haven railroad, signed on as a muleteer on the British Cargo steamer Esmeraldas, which was sailing from Newport News to Liverpool with a cargo of 950 horses. At about 2:00 AM on March 10, the twelfth day of the voyage, the ship was overtaken by the German commerce raider SMS Möwe, shown above.

Smith was awakened by another crew member who announced, “they’ve got us,” to see the Möwe lying astern. Smith reported that the Möwe “looked like a tramp steamer, but it could travel, believe me. It had eight guns forward under a folding deck, and when it fought they raised the ship sides. They lowered them after battle and then it looked harmless.”

Soon, the ship was swarming with Germans, three of whom carried bombs. They took the 350 crew and passengers off and proceeded to blow up the Esmeraldas.

Smith reported that the prisoners were treated well aboard the Möwe, but also served as unwitting participants in five more battles as the Möwe continued her raids. On March 21, the ship reached harbor at Kiel, which was “full of warcraft, battleships, and hydroplanes, and it was a pretty sight to watch the hydroplanes darting down to the water like gulls.” The prisoners remained in Kiel for four days, and then another two weeks in Durmen. From there, they were taken to a prison camp near Brandenburg on April 4, and “we were in that dump until early in May. They pushed us and shoved us a good deal and called us swine and some other things.” Food consisted of “one chunk of bread daily and turnip soup. That turnip soup was good water spoiled.”

At some point in May, Smith and several hundred other prisoners were transferred to Lubeck, where they were put to work on the docks loading ships bound for Sweden. When the German freighter Undine was being loaded, Smith came up with his escape plan.

Prisoners were marched to the deck in groups of twelve at 6:00 AM, but Smith noted that men who had reported sick were not seen until later in the morning. So Smith reported himself sick. When the men were marched to the dock the next morning, he waited until a group had been counted, and then slipped in. The guards didn’t bother counting during the march, and they didn’t expect an extra man. At the dock, he joined in the loading. As soon as he was aboard, he hid himself in the hold along with the load of fertilizer. He remained there from Saturday morning to Friday morning of the next week. “It was dark, but I had a pocket lamp that lasted quite a while.”

Smith had brought some food, some crackers, but didn’t bring any water. Therefore, he was unable to eat “because my mouth and throat got so dry I would not swallow them. I tried to eat them, but they were like sand in my mouth and would not go down. All the time I was afraid and my tongue was getting bigger and bigger. It felt a foot thick.”

A few times, Smith considered going up and turning himself in, but after remembering the conditions at Brandenburg, he decided to wait.

On Thursday night, the ship docked at Norrköping, Sweden. In the morning, “looking like a wildman, a week’s growth of beard on his face, his tongue swolen from six days’ raging thirst, eyes blazing with fever, body shaking with nervous chills, but still full of fight,” Smith made a leap from the deck of the ship into the arms of a Swedish dock policeman. The Swedish stevedores, realizing the situation and manifestly sympathetic, shouted to the policeman to hustle Smith away from the ship.

After Smith’s imploring gestures, he was ushered to a hydrant “where he thinks he must have drunk a gallon of water without stopping, the policeman patting him on the shoulders the while.” He was taken to the police station and a telegram was sent to the U.S. Consulate in Stockholm.

The Chicago Tribune correspondent and a few others chipped in to buy Smith a suit of clothes, after which “Smith began to look really respectable.” The American Vice Consul went to the station to get Smith, saying that “I thought he’d proved himself a good American and deserved welcome,” and the consulate was making arrangements to send him home.

The following German propaganda film shows a number of the exploits of the Möwe, which was the most successful German raider of both wars.