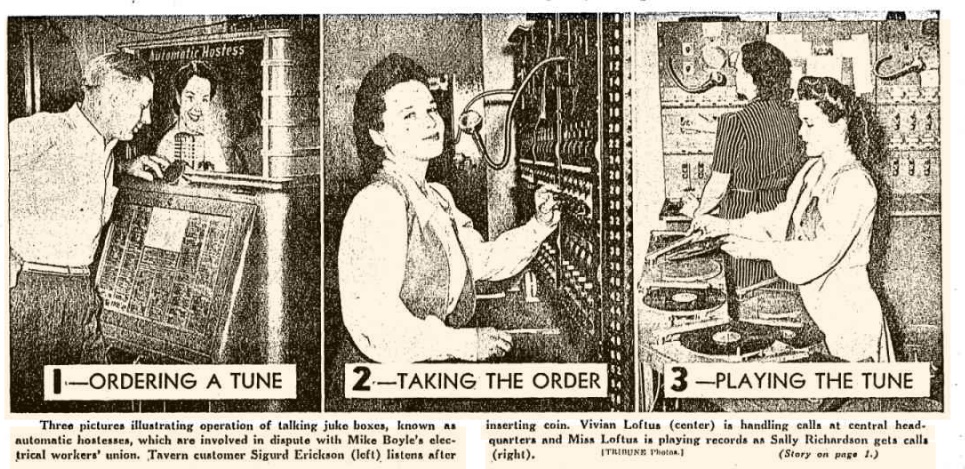

Seventy-five years ago today, the Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1941, offered an interestingly candid look at the juke box industry in Chicago. Typically, a juke box would contain 20 records, and the patron put in a nickel in exchange for playing one of them.

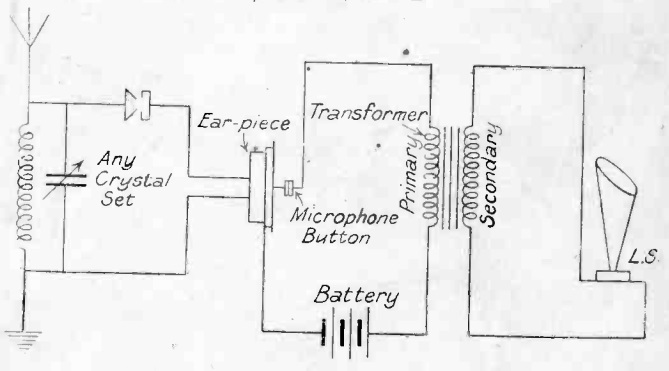

Things changed when the K.P. Music corporation of 1057 Wilson Avenue came along with talking juke boxes known as “automatic hostesses.” Instead of twenty records, the patron had a choice of 680 records. When the patron inserted his coins, he was connected, via leased telephone line, to a hostess at 1057 Wilson Avenue, with whom he could exchange banter, make a request, and even dedicate a particular number to his friends.

Eighteen taverns quickly signed up and junked their old jukes. This went over well with everyone, with one exception, and that was Michael J. Boyle, also known as the “Umbrella Man,” the head of the Electrical Workers’ union. He had two objections. He first argued that the new jukes were too good, and that hundreds of traditional juke boxes were in other taverns, with hundreds of dollars tied up. The new talking juke boxes would cut in too heavily, making the investment a “dead loss.”

Umbrella Mike got his name from his practice of hanging an umbrella from the bar when making a visit. The owner of the tavern could then conveniently deposit an envelope into the umbrella so that Mike could be on his way with a minimum of fuss.

The old machines were serviced by, and more importantly, in the territory “belonging to” the Apex Cigaret Company of 4220 Lincoln Avenue. Depiste the name, Apex wasn’t in the cigarette business. Its business was juke boxes.

The newspaper identified Joseph “Gimp” Mahoney as the nominal president of Apex, “but Eddie Vogel, old time Capone gangster, is known as the power behind it. Those gentlemen’s relations with Mr. Boyle are cordial.”

To express their displeasure, the union’s business agent, along with about a half dozen members of the union, showed up at the 18 bars in question. They carried signs announcing that the talking jukes were “unfair to organized labor.” After picketing for a bit, the business agent would slip inside and unplug the machine. He also left some advice to the owners that “it was in their best interests that the boxes remain silent.”

Eleven of the 18 taverns took the advice, but at seven others, “the tavern owners showed the agent the door and the talking jukes went on talking.”

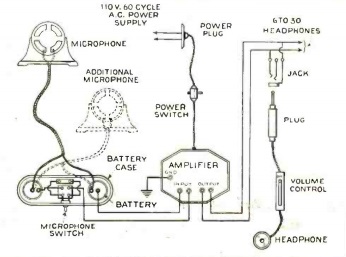

The newspaper reporter visited the talking jukebox studio and described the operation. The “hostess,” Miss Mickie Martin, shown above at the microphone, would be signaled by a light that some business was coming in from one of the taverns. Another indicator would show how many nickels had been fed in. Confirming that payment had been received, she would flip the switch and say sweetly, “hello, what can I do for you?”

The reporter noted that many voices would come over the wire, both old and new. “Some were those of strangers, some those of old friends who’d built up an acquaintance thru many nickels with Mickie.”

In one case, the connection was interrupted, and Mickie advised that they were having trouble at that establishment, since the business agent was there.

The firm’s attorney was dispatched to the bar in question, but by the time he arrived, the agent had pulled the plug and left the scene. The attorney lamented, “I’ve got 17 cousins on the police force, but what can you do when you run up against this kind of stuff?”

And not insignificantly, the old juke boxes were serviced by members of his own union.

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

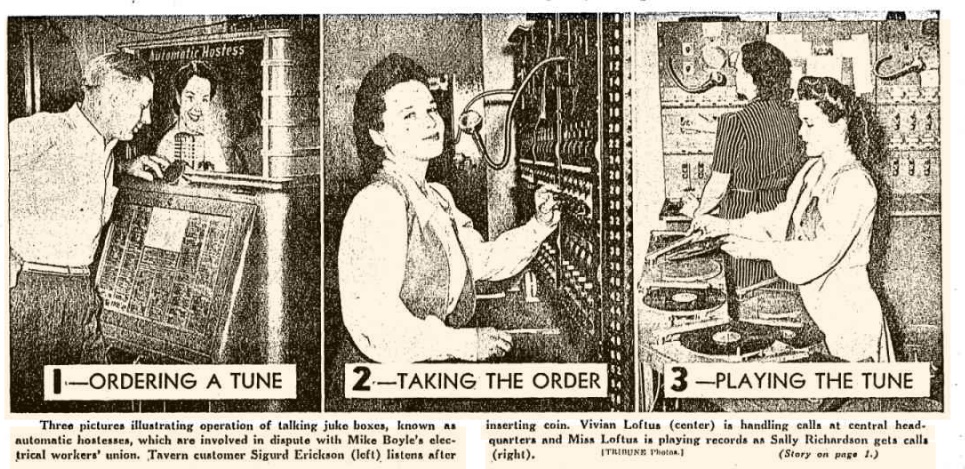

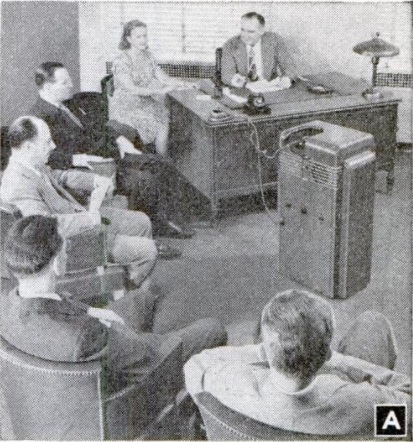

Today, most telephones, either landline or mobile, contain a speaker phone function, but this hasn’t always been the case. Shown here from 70 years ago is a very early version, the Jordaphone, shown here in the January 1948 issue of Popular Mechanics. The article notes that groups could now sit in on meetings without individual telephones with the instrument that “looks like a console radio.”

Today, most telephones, either landline or mobile, contain a speaker phone function, but this hasn’t always been the case. Shown here from 70 years ago is a very early version, the Jordaphone, shown here in the January 1948 issue of Popular Mechanics. The article notes that groups could now sit in on meetings without individual telephones with the instrument that “looks like a console radio.”