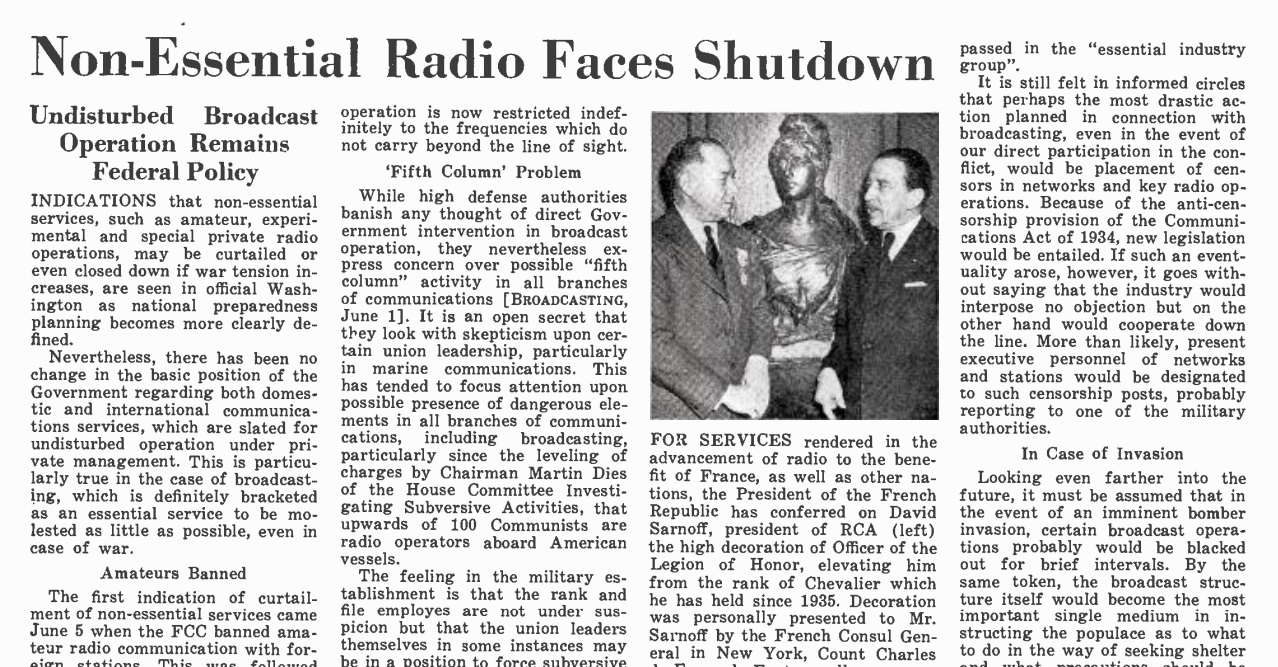

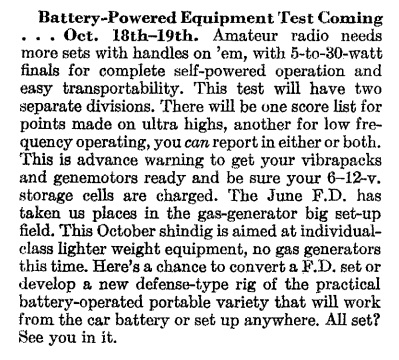

Today marks the 80th anniversary of an ARRL contest that, as far as I can tell, happened only one time, the 1941 ARRL Battery-Powered Equipment Test. The announcement shown here appeared in the September 1941 issue of QST, and the full rules appeared in the October issue.

Today marks the 80th anniversary of an ARRL contest that, as far as I can tell, happened only one time, the 1941 ARRL Battery-Powered Equipment Test. The announcement shown here appeared in the September 1941 issue of QST, and the full rules appeared in the October issue.

While June Field Day was, and is, dominated by gasoline powered generators, this event was “aimed at individual-class lighter weight equipment.” To stress this, the official contest exchange included the transmitter weight. Participants could work non-contest stations for one point, with an extra point for sending and getting acknowledgment of the transmitter weight. If the other station was battery powered, there was an additional point for copying their transmitter weight.

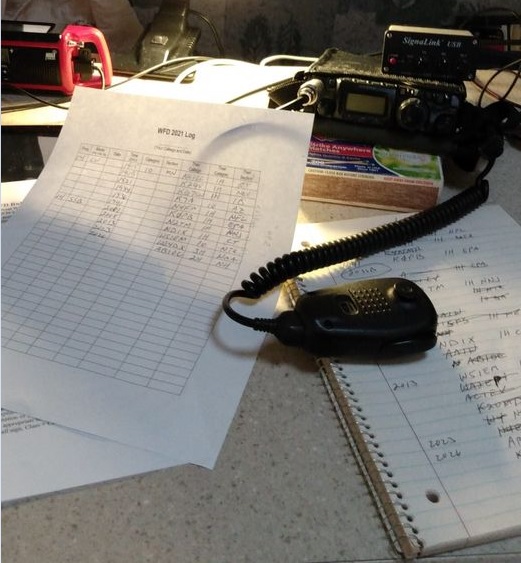

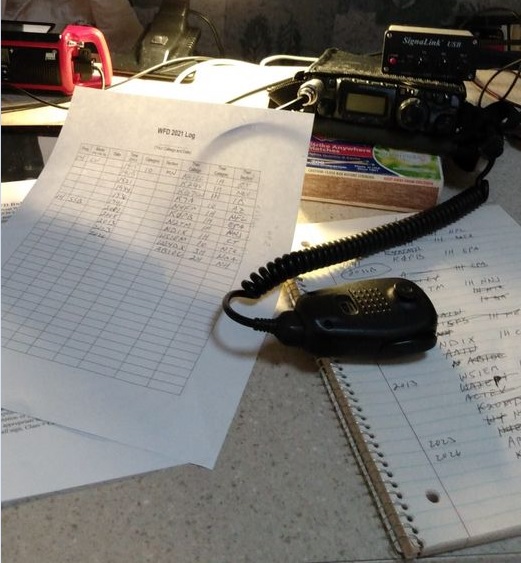

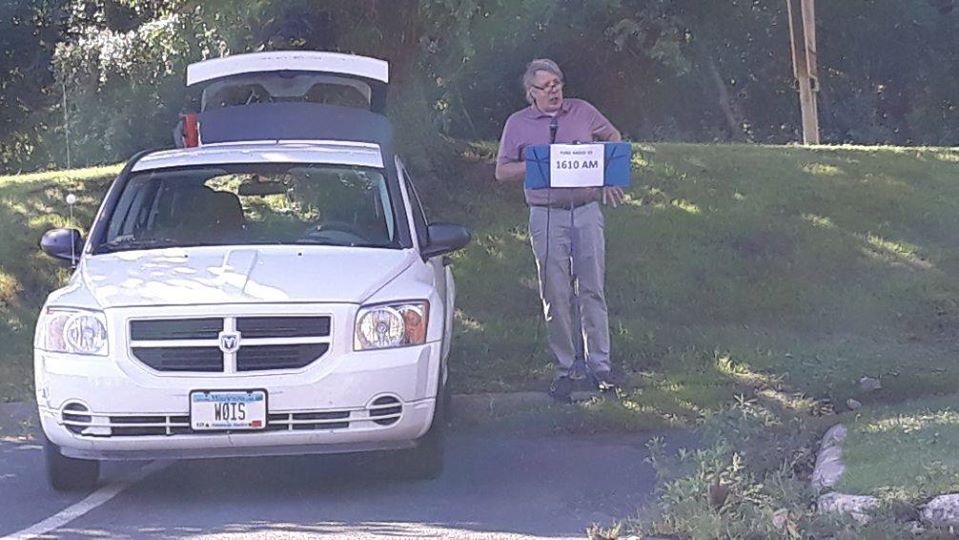

In my opinion, the small advantage gained by an electric generator is more than offset by the convenience of operating with batteries. For example, as I previously reported, I worked the 2021 Winter Field Day contest with my trusty fish finder battery. Especially if you’re thinking in terms of emergency preparedness, it’s an easy matter to keep fully charged batteries on hand, whereas a generator usually requires a certain amount of maintenance, as well as keeping fuel on hand.

In my opinion, the small advantage gained by an electric generator is more than offset by the convenience of operating with batteries. For example, as I previously reported, I worked the 2021 Winter Field Day contest with my trusty fish finder battery. Especially if you’re thinking in terms of emergency preparedness, it’s an easy matter to keep fully charged batteries on hand, whereas a generator usually requires a certain amount of maintenance, as well as keeping fuel on hand.

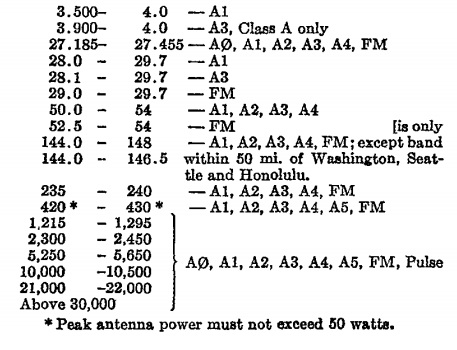

The maximum power level for the 1941 contest was set at 30 watts, although it would have been a stretch to get more from battery-powered equipment. Operation from the field was encouraged, with a multiplier of of 2 for all contacts. However, stations could also be operated from home, as long as batteries provided all power for transmitter and receiver. The contest rules reminded hams that portable operation required 48 hours advance notice to the FCC.

There were categories for both HF and VHF (called in those days “low frequency” and UHF). Interestingly, HF operation was confined to the daylight hours, but UHF could continue all night. The UHF category allowed 5 meters and up, but all of the entries in that category used exclusively the 2-1/2 meter band.

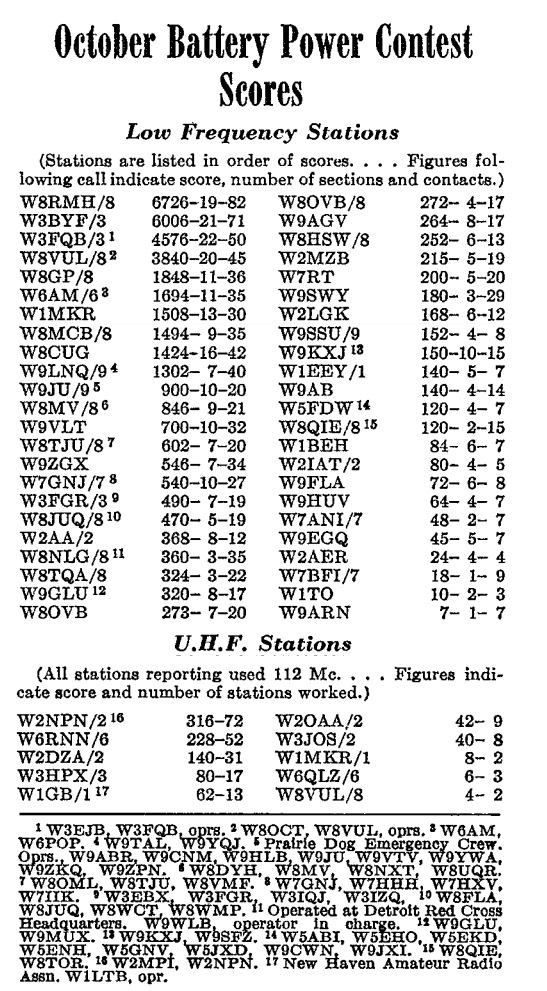

The results weren’t published until after Pearl Harbor, in the March 1942 issue of QST. They are shown below, with W8RMH, Edgar Cantelon of Detroit, later W8CV, taking the honors for high score with 82 contacts from a portable location. Among the calls is one familiar one, that of Don Wallace, W6AM, whom we have previously profiled.

In the “UHF” category, W2NPN took top honors, with an impressive 72 contacts from a portable location, all on 112 MHz.

The “transmitter weight” is an interesting piece of data to exchange. Even though this contest is no more, transmitter weight is still a factor in at least one contest. While it’s not sent on the air, transmitter weight is an important factor in scoring for the Adventure Radio Society Spartan Sprint contest. In the most recent running, K4PQC managed 11 contacts with a station (transmitter, receiver, headphones, and battery) weighing in at 0.1268 pounds (2 ounces). He reported that his station consisted of a 40 meter ATS-3b. The rig is designed to fit inside an Altoid’s tin, but he ran it without the case to shave a whopping 1.2 ounces off the station weight.

I suspect W8RMH’s rig weighed a bit more in 1941, but he probably used a lot of other gear, both larger and smaller, over the years. According to his 2016 obituary, he had just started working at WJBK radio (now WLQV) shortly after this contest, and he was in the transmitter room when the station reported that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. He then secured a new job in a defense plant, later becoming a radio operator for bomber test flights. He later served in the Merchant Marine as a radio operator, and then the army. He later went back to WJBK and served as an engineer for their TV station.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning this site earns a small commission if you click on the link and make a purchase.