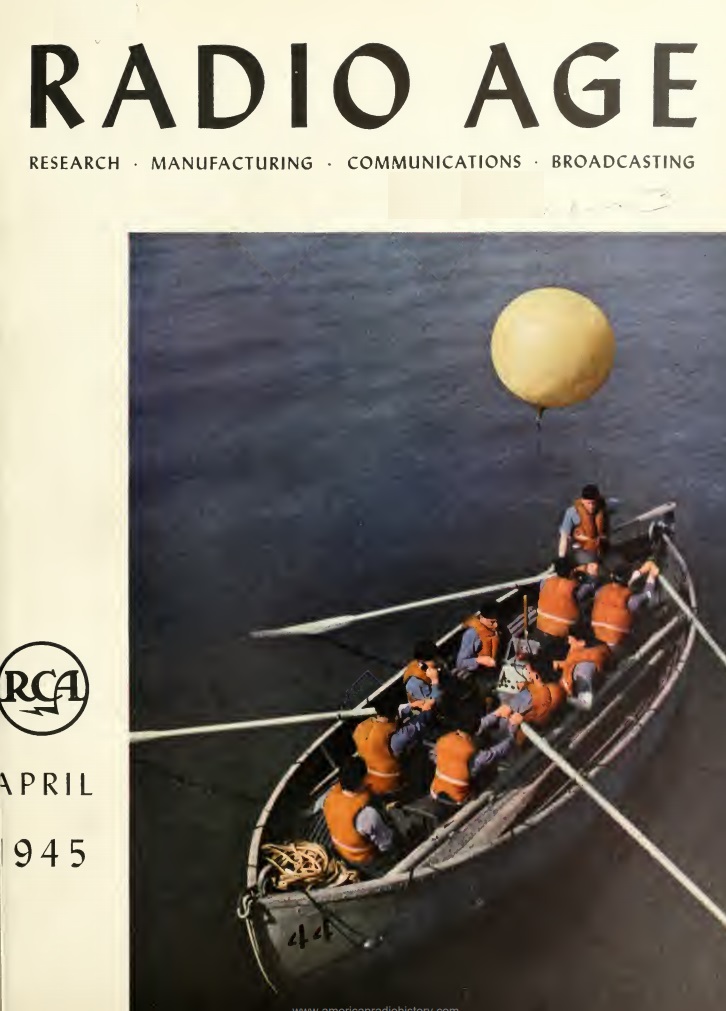

We previously featured the Radiomarine Corporation of America’s model ET-8030 lifeboat radio. While the set was never deployed during the war, it was featured in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, a quarterly magazine published by RCA. It is featured on the cover of the magazine, being operated by cadets at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, N.Y..

We previously featured the Radiomarine Corporation of America’s model ET-8030 lifeboat radio. While the set was never deployed during the war, it was featured in the April 1945 issue of Radio Age, a quarterly magazine published by RCA. It is featured on the cover of the magazine, being operated by cadets at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, Kings Point, N.Y..

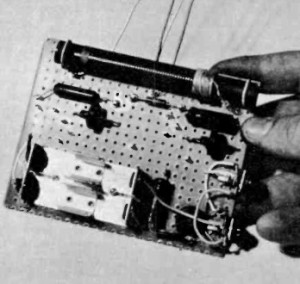

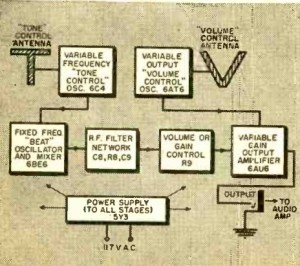

The set, permanently mounted in the lifeboat, operated with a hand crank which provided the power and keyed the transmitter. In the automatic mode, the set would send a long dash and SOS on 500 kHz and 8280 kHz. It could also be switched into the manual mode, which allowed voice transmission, and included a receiver for both 500 kHz and 8100-8600 kHz. The set could be used with an inveted vee antenna mounted to the boat’s mast, but the most prominent feature was a helium balloon which could hoist the antenna to height of 300 feet and keep it there for a week. As a backup, a box kite was also provided.

The set, permanently mounted in the lifeboat, operated with a hand crank which provided the power and keyed the transmitter. In the automatic mode, the set would send a long dash and SOS on 500 kHz and 8280 kHz. It could also be switched into the manual mode, which allowed voice transmission, and included a receiver for both 500 kHz and 8100-8600 kHz. The set could be used with an inveted vee antenna mounted to the boat’s mast, but the most prominent feature was a helium balloon which could hoist the antenna to height of 300 feet and keep it there for a week. As a backup, a box kite was also provided.