A hundred years ago today, the young entrepreneur wishing to acquire a wide variety of interesting products couldn’t go wrong by getting him or herself into the bluing business, courtesy of this ad from the Washington Times, August 20, 1922. I suppose a few kids might have desired the football, the doll, or the dollhouse, but we would like to think that the more popular items were the telescope, the camera, the air rifle, or the moving picture machine. The “school box with fountain pen” is notable for the fact that it includes a knife. If a kid today showed up with a school box containing a pocket knife, the SWAT team would probably be called in, and the poor kid expelled. But a hundred years ago, it was perfectly normal for a kid to bring this useful tool with him to school.

A hundred years ago today, the young entrepreneur wishing to acquire a wide variety of interesting products couldn’t go wrong by getting him or herself into the bluing business, courtesy of this ad from the Washington Times, August 20, 1922. I suppose a few kids might have desired the football, the doll, or the dollhouse, but we would like to think that the more popular items were the telescope, the camera, the air rifle, or the moving picture machine. The “school box with fountain pen” is notable for the fact that it includes a knife. If a kid today showed up with a school box containing a pocket knife, the SWAT team would probably be called in, and the poor kid expelled. But a hundred years ago, it was perfectly normal for a kid to bring this useful tool with him to school.

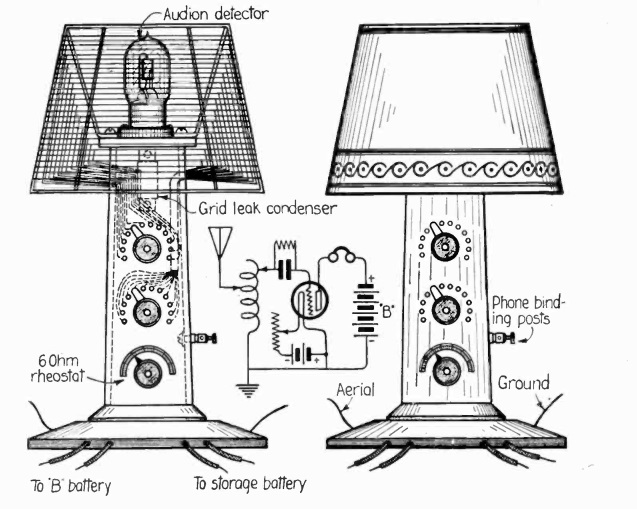

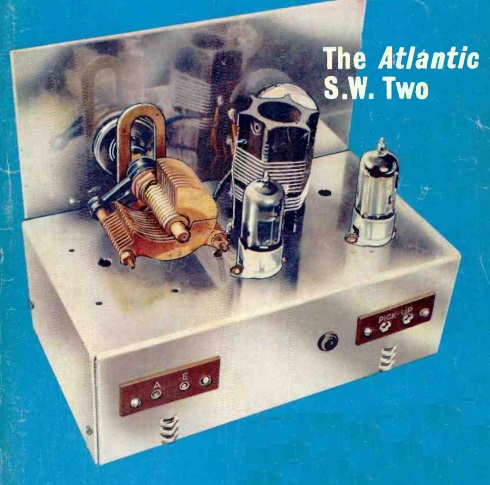

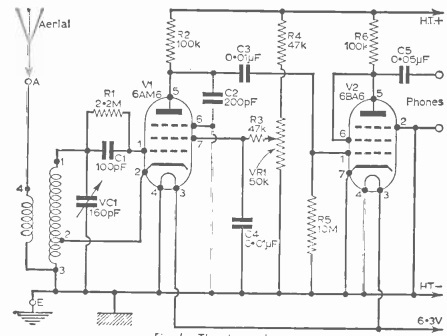

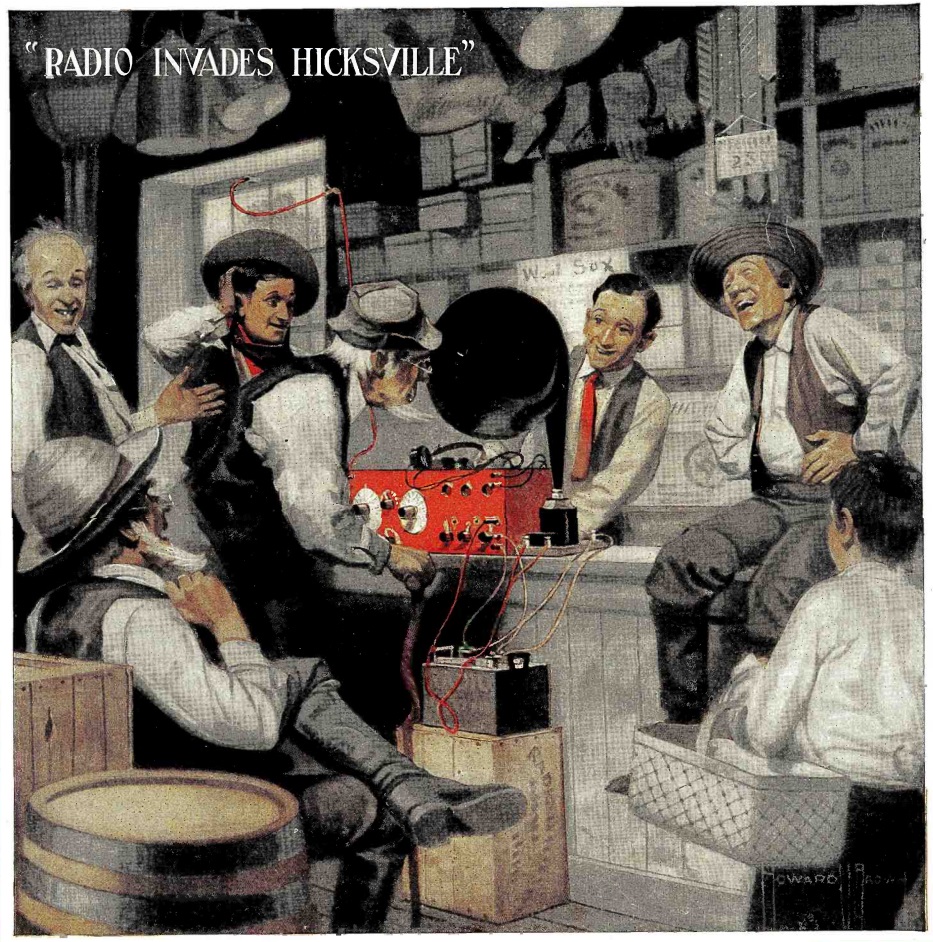

Of course, the most interesting item available was the radio. According to the ad, this fine Radio Receiving Set was a genuine scientific instrument, made of first class material. It included the tuning coil, detector, and condenser and was capable of pulling in stations from 15-25 miles away. With it, the young salesman could catch messages, singing, lectures, and radio news of all sorts. The whole family would enjoy it.

To earn the radio, the youngster would need to sell 28 packages of bluing at 10 cents each. Now, if that youngster reads the ad carefully, he will notice that the ad doesn’t say anything about a headphone being included. So unless Junior happened to already own a headphone, he would need to sell 28 more packages of bluing to earn the radio ear piece.

But still, making sales totaling $5.60 seems pretty reasonable and achievable. So to get started, the young salesperson just needed to write to the Bluine Mfg. Co., 150 Mill St., Concord Junction, Mass.

Perhaps some readers have gotten this far and don’t know what “bluing” is. It was more common back in the day, but it’s not used so much any more. “Bluing” is simply a blue dye, a small amount of which is added to the rinse water when washing white items. The effect is to make the whites whiter, since they turn grey or yellow with age. The blue dye covers up these colors, giving the illusion that the cotton fabric is whiter. The bluing provided by the Bluine Mfg. Co. was impregnated into pieces of paper, which were sold a dozen to the package. Therefore, they were easy not only to toss in the wash, but also to send through the mail, making the product ideal for this type of distribution.

Even though it’s less popular today, to the point where most people haven’t heard of it, the laws of physics haven’t changed since 1922, and adding a bit of bluing to the whites will still have the same effect of making them whiter. And as with everything else, you can still buy it on Amazon at the links below. Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear to be available impregnated in small pieces of paper. Instead, it comes in a liquid, or in a small solid square. You cut off a small piece and mix with warm water to make your own liquid. Since you use only a few drops, and of these will probably last the typical household years.

Some links on this site are affiliate links, meaning that this site earns a small commission if you make a purchase after using the link.

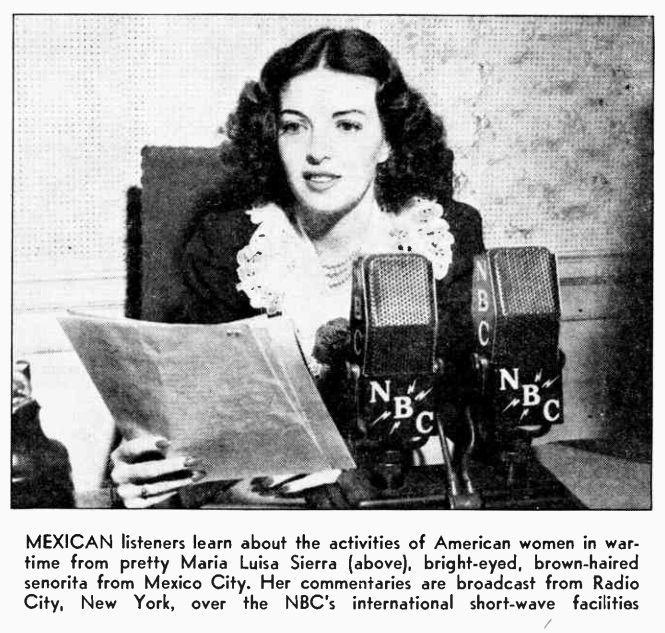

A hundred years ago today, the August 22, 1922, issue of the Washington Evening S carried this ad for the radio department of Lansburgh’s Department Store.

A hundred years ago today, the August 22, 1922, issue of the Washington Evening S carried this ad for the radio department of Lansburgh’s Department Store.