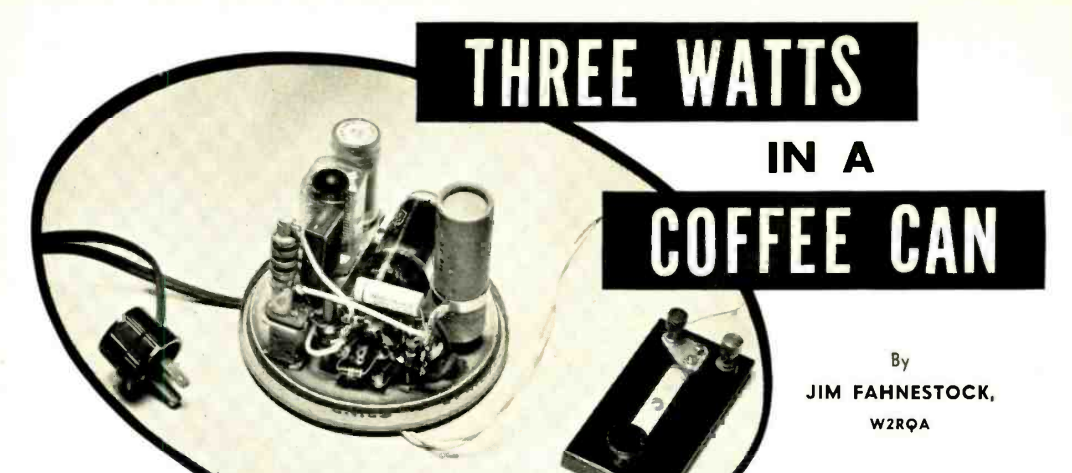

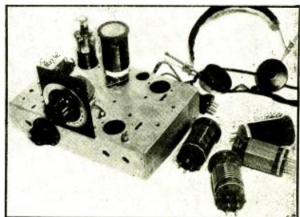

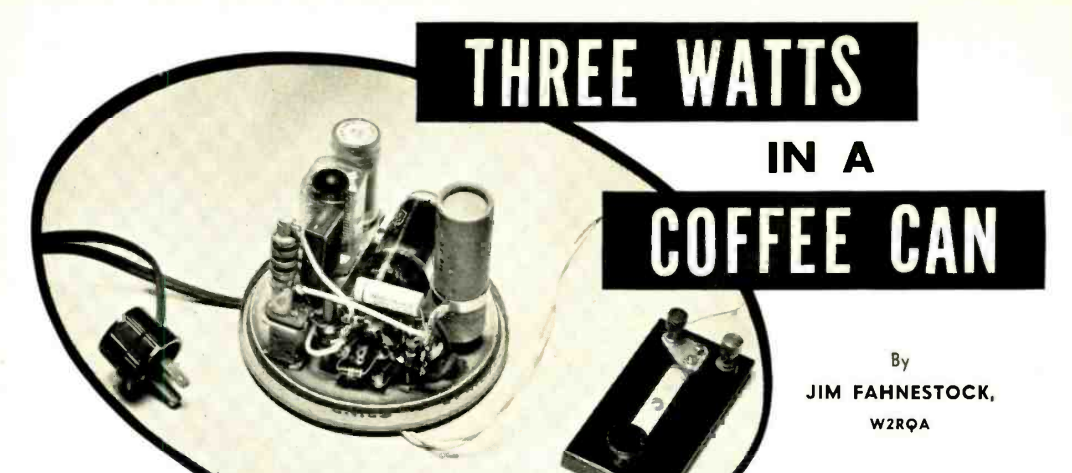

Many hams from the 1970s and later are familiar with variations on W1CER’s (later W1FB) Tuna Tin II, a transmitter which used a tuna can as its enclosure. But the 1950s had its own variation on the same theme, as shown here in the June 1953 issue of Radio News. A 117L7GT tube wouldn’t fit inside a tuna can, but it did fit into a coffee can, so that’s what was used.

Many hams from the 1970s and later are familiar with variations on W1CER’s (later W1FB) Tuna Tin II, a transmitter which used a tuna can as its enclosure. But the 1950s had its own variation on the same theme, as shown here in the June 1953 issue of Radio News. A 117L7GT tube wouldn’t fit inside a tuna can, but it did fit into a coffee can, so that’s what was used.

This 80-meter transmitter was actually a club project by the Wantah Radio Club on Long Island, New York. It was designed to spur some activity as the club members built and used them. Once the rigs were built, they used them for local nets, and also used them for contests, such as for the most distant contact, and the highest number of states worked.

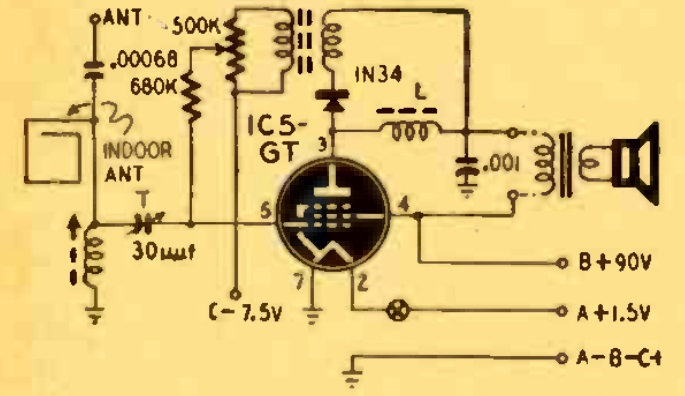

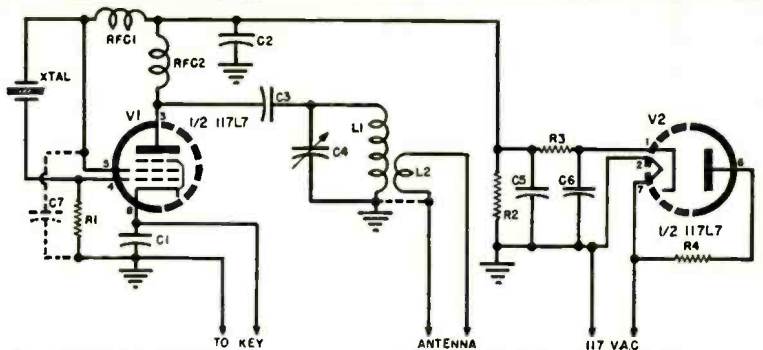

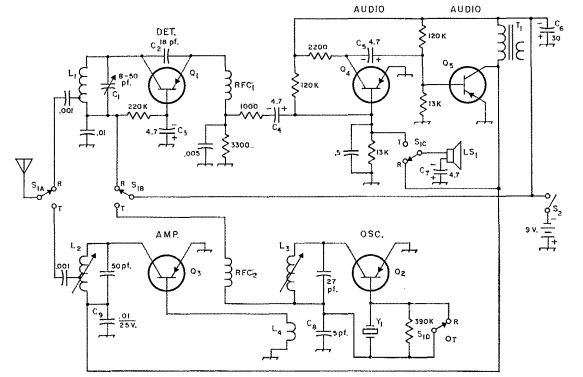

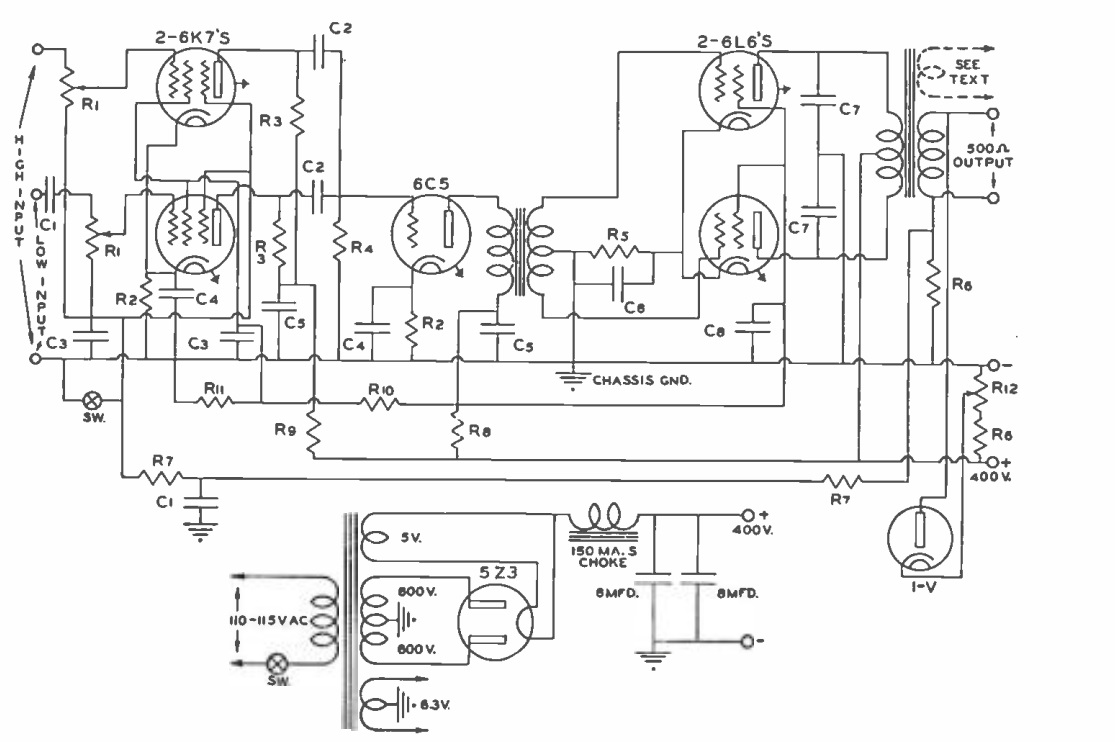

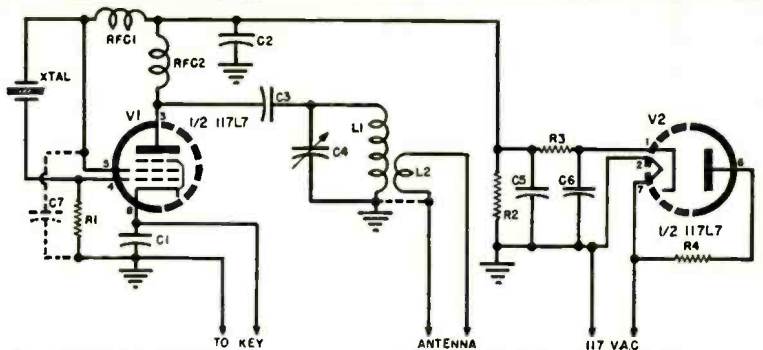

Half the tube was used as a Pierce oscillator, with the other half serving as rectifier. We’ve seen other transmitters using the same tube, and it’s a natural for a small one-tube QRP rig. This design put out about 3 watts, and the station on the other end was often surprised by the power used. The article warned that to save money, half of the line cord was attached to the chassis, making it potentially hot. Therefore, those making the set were cautioned to use care in plugging the cord in with the right polarity. They described a test circuit to see if it was plugged in the right way, but that circuit would trip a modern GFCI outlet.

The tuning circuit shown in the schematic below was “already mounted on a convenient subchassis from a BC-746 tuning unit available at surplus,” as if everyone knew what a BC-746 was. That appears to be an external antenna tuner, one portion of which was used here. If you can’t find a BC-746, the article gives alternatives for making your own.

The set was mounted on the coffee can lid, with the can itself then used as the enclosure. This was said to provide shielding to prevent TVI.

The author of the article was Jim Fahnestock, W2RQA. There can’t be that many Fahnestocks in the world, and since he was from New York, where the famed Fahnestock clip originated, we have to guess that he was related to the inventor of the clip and the namesake of the State Park.

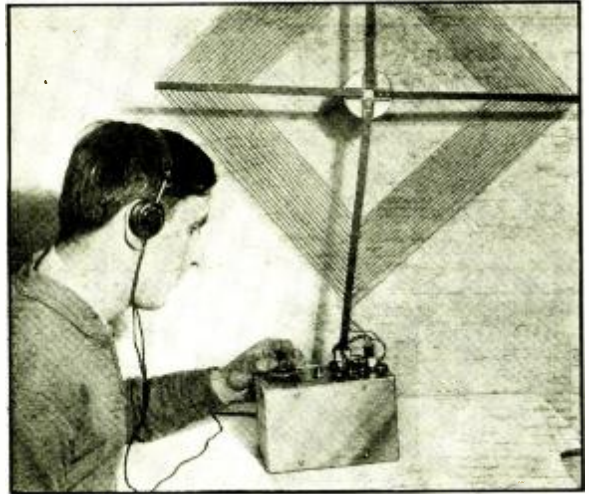

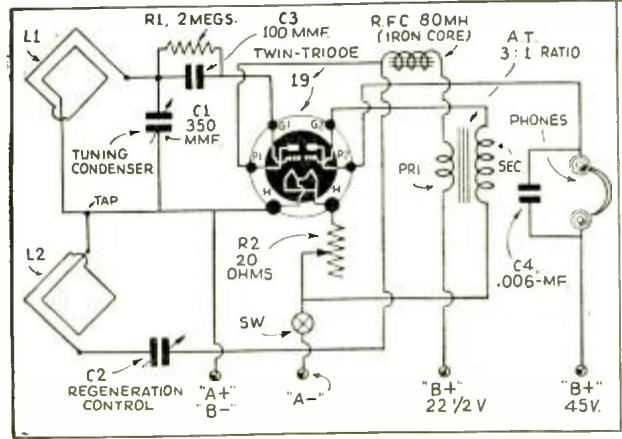

The summer of 1923 was to be a big one for radio, as predicted by the June 1923 issue of Wireless Age. The magazine editorialized that radio would be a major feature of summer camp experiences, and many farm families would be introduced to radio by their city visitors.

The summer of 1923 was to be a big one for radio, as predicted by the June 1923 issue of Wireless Age. The magazine editorialized that radio would be a major feature of summer camp experiences, and many farm families would be introduced to radio by their city visitors.