Gracing the cover of Radio News 75 years ago this month, May 1949, is the mobile unit of WKY, Oklahoma City. The unit was custom built, and was complete with both transmitting and receiving antennas for AM and FM.

Gracing the cover of Radio News 75 years ago this month, May 1949, is the mobile unit of WKY, Oklahoma City. The unit was custom built, and was complete with both transmitting and receiving antennas for AM and FM.

Gracing the cover of Radio News 75 years ago this month, May 1949, is the mobile unit of WKY, Oklahoma City. The unit was custom built, and was complete with both transmitting and receiving antennas for AM and FM.

Gracing the cover of Radio News 75 years ago this month, May 1949, is the mobile unit of WKY, Oklahoma City. The unit was custom built, and was complete with both transmitting and receiving antennas for AM and FM.

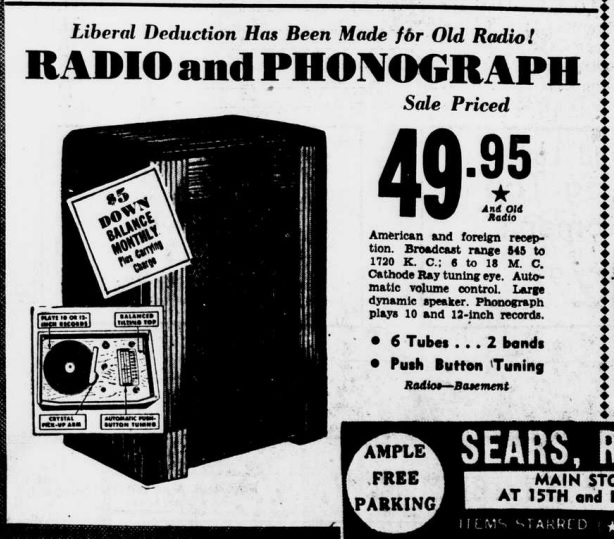

If you were in the market for a new radio-phono 85 years ago, Sears was the place to go. They would give you a liberal allowance for your trade-in. For only $49.95 plus your old radio (or just $5 down), you could go home with this two-band receiver. The broadcast band went up to 1720 kHz, so you would be able to pull in police calls. And the 6-18 MHz shortwave band meant that you could listen to the news direct from Europe.

If you were in the market for a new radio-phono 85 years ago, Sears was the place to go. They would give you a liberal allowance for your trade-in. For only $49.95 plus your old radio (or just $5 down), you could go home with this two-band receiver. The broadcast band went up to 1720 kHz, so you would be able to pull in police calls. And the 6-18 MHz shortwave band meant that you could listen to the news direct from Europe.

The ad appeared in the May 28, 1939, issue of the Washington Evening Star.

While her sons, son-in-law, and granddaughter were off to war, Mrs. Louise Oeser does her part by calibrating radio transmitters for GE at Schenectady, NY.

While her sons, son-in-law, and granddaughter were off to war, Mrs. Louise Oeser does her part by calibrating radio transmitters for GE at Schenectady, NY.

This item appeared in the May 1944 issue of Radio Craft.

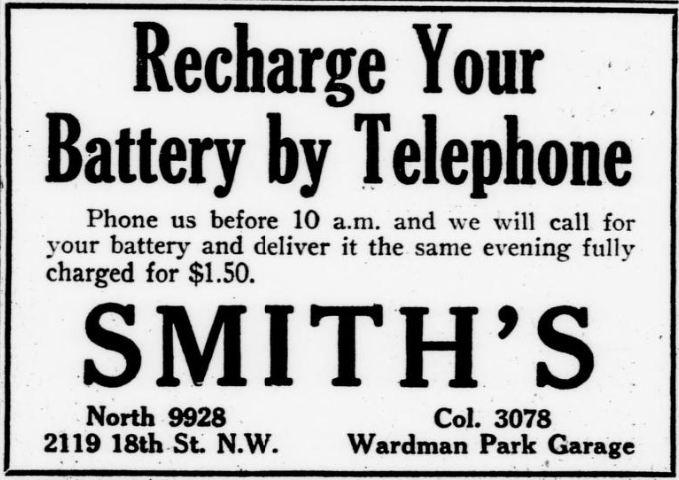

A hundred years ago, if your radio battery was dead, you could get it charged by phone, kind of. You could call before 10:00 AM, the service station would come and pick it up, and you would have it back in time to pull in the DX that evening.

A hundred years ago, if your radio battery was dead, you could get it charged by phone, kind of. You could call before 10:00 AM, the service station would come and pick it up, and you would have it back in time to pull in the DX that evening.

The ad appeared in the Washington Evening Star, May 25, 1924, and the service was offered by Smith’s, 2119 18th St. NW, Washington, DC.

No family picnic is complete without getting on the air and making some 2 meter QSOs, as shown 70 years ago this month on the cover of Radio News, May 1944. While mom gets lunch ready and junior looks on, dad is making some contacts with his Gonset Communicator, which can operate on either 117 volts AC or 6 volts DC.

The magazine contained an article describing the then-new offering. It noted that it was considerably more sophisticated than prewar rigs. While the target market for the rig was hams, the magazine noted that it was also suitable for CAP use, or even as the UNICOM frequency of a small airport.

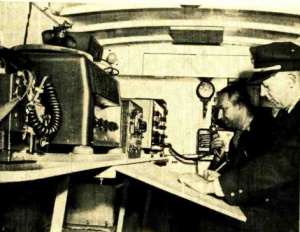

Shown above is the 1939 Studebaker employed in 1954 by the City of Malden, Mass., as its mobile emergency communications center. Shown at left are Sgt. Orin Hood, W1LD, of the Malden Police Department, along with Eli Nannis, W1HKG, the city’s radio officer and emergency coordinator.

Shown above is the 1939 Studebaker employed in 1954 by the City of Malden, Mass., as its mobile emergency communications center. Shown at left are Sgt. Orin Hood, W1LD, of the Malden Police Department, along with Eli Nannis, W1HKG, the city’s radio officer and emergency coordinator.

The photos and description appeared 70 years ago this month in the May 1954 issue of Radio Electronics, which explained how such a station could be set up on a reasonable budget. The Studebaker patrol wagon was about to be surplussed by the police department. It had been rarely used, and was in good condition.

The City was also going to get rid of a 1800-watt gasoline generator, and it was obtained and placed on a two-wheel trailer.

For radio equipment, it was equipped with a Harvey Wells model TBS-50C transmitter and National NC-183 receiver. As a backup station, the truck was equipped with a 10-watt 10 meter transmitter, and a car radio and converter. That station could run off the truck batteries. The truck also contained a radio for police frequencies, as well as telephones and wire for hooking them up as needed.

The station had already been put into service when tornadoes struck nearby Worcester.

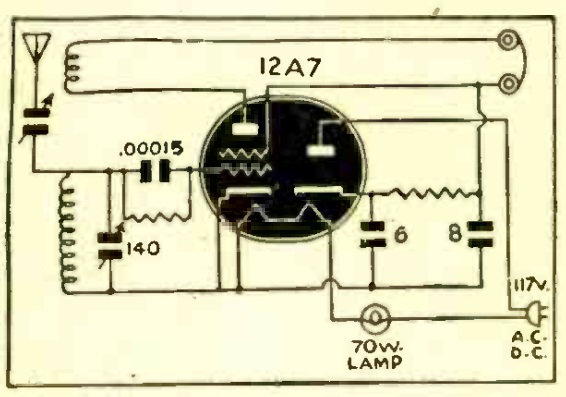

Eighty years ago this month, the May 1944 issue of Radio Craft carried this circuit for a one-tube receiver. It had been sent in to the magazine by one Bob Smith of Montclair, NJ, who pointed out that standard plug-in coils could cover the shortwave and broadcast bands. He added one word of caution, “do not ground set.” This, of course, is because it was running straight off the AC line, and if you grounded it, there would be a 50/50 chance that you would short out the power. We, of course, will add another word of caution, namely, not to touch anything. The headphones are hot, strapped right to your head. So if you touch a grounded object nearby, there’s a 50/50 chance that the resulting current would run right through you.

Eighty years ago this month, the May 1944 issue of Radio Craft carried this circuit for a one-tube receiver. It had been sent in to the magazine by one Bob Smith of Montclair, NJ, who pointed out that standard plug-in coils could cover the shortwave and broadcast bands. He added one word of caution, “do not ground set.” This, of course, is because it was running straight off the AC line, and if you grounded it, there would be a 50/50 chance that you would short out the power. We, of course, will add another word of caution, namely, not to touch anything. The headphones are hot, strapped right to your head. So if you touch a grounded object nearby, there’s a 50/50 chance that the resulting current would run right through you.

A 70-watt lightbulb is used to drop the filament voltage to 12.5 volts to light the filament of the 12A7 tetrode/diode tube.

A hundred years ago today, the May 16, 1924 issue of the Washington Star carried this item. Many listeners had graduated to tube sets, and radio executive Le Roy Mark wanted to see to it that their old crystal sets made it into the hands of the poor and needy of Washington. He had begun an ongoing campaign to collect old crystal sets at Piggly Wiggly and Peoples Drug stores in the District, from whence they would make it into the hands of the needy. 400 names had already been collected, but Mark requested that clergymen and physicians send him the names of others who might benefit.

A hundred years ago today, the May 16, 1924 issue of the Washington Star carried this item. Many listeners had graduated to tube sets, and radio executive Le Roy Mark wanted to see to it that their old crystal sets made it into the hands of the poor and needy of Washington. He had begun an ongoing campaign to collect old crystal sets at Piggly Wiggly and Peoples Drug stores in the District, from whence they would make it into the hands of the needy. 400 names had already been collected, but Mark requested that clergymen and physicians send him the names of others who might benefit.

The Boy Scouts of the District had volunteered to install the sets. The only expense would be the cost of antenna wire, and contributions were being solicited for that purpose.

According to his 1938 obituary, Mark was a pioneer of radio broadcasting in Washington, as well as the insurance industry. The obituary still remembered him as “a leader in the campaign to provide funds to furnish radio sets to all shut-ins, particularly to make available a sufficient number of sets to enable all hospitalized World War veterans to listen to radio programs.”

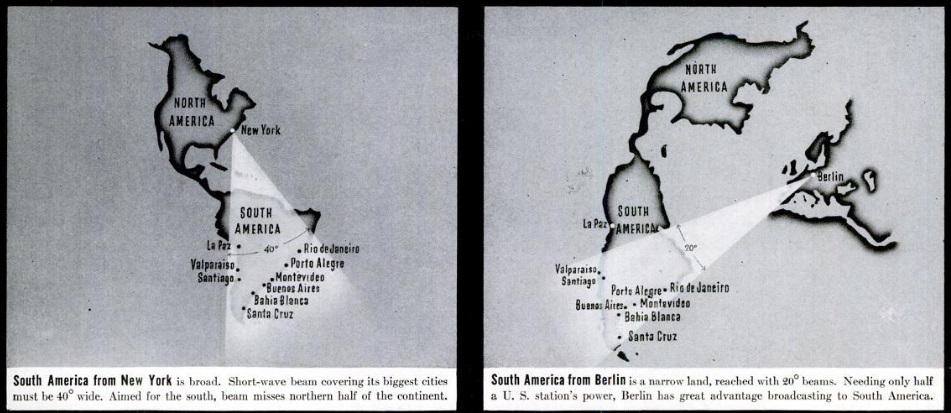

Eighty-five years ago, all of the countries that would soon be at war were gearing up for the inevitable propaganda battles, and the May 15, 1939, issue of Life magazine explained some of the technical issues involved. The Germans had an advantage when it came to broadcasting to South America, since their beam could be only half the width required by the Americans to cover the major population centers.

Eighty-five years ago, all of the countries that would soon be at war were gearing up for the inevitable propaganda battles, and the May 15, 1939, issue of Life magazine explained some of the technical issues involved. The Germans had an advantage when it came to broadcasting to South America, since their beam could be only half the width required by the Americans to cover the major population centers.

But as far as broadcasting to the respective homelands, the Americans had the advantage. They could blanket Europe with a narrow beam, whereas the signal from Berlin would need to be extremely wide to cover all of the United States.

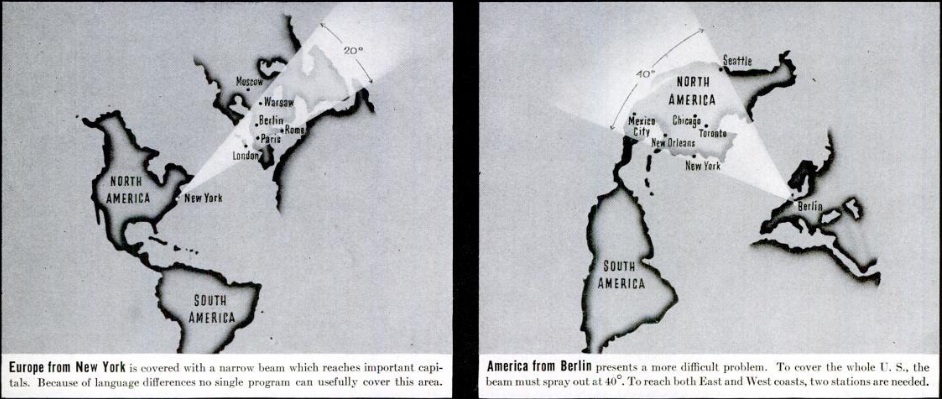

This gentleman’s technique with the canoe paddle leaves something to be desired, but his girl doesn’t even notice, because she is enthralled with the portable radio he had the foresight to bring along on their date.

This gentleman’s technique with the canoe paddle leaves something to be desired, but his girl doesn’t even notice, because she is enthralled with the portable radio he had the foresight to bring along on their date.

Eighty-five years ago, portable radios were a hot commodity, and the May 1939 issue of Radio Today carried some pointers for selling them. In addition to the normal ideas of direct mail, window displays, etc., it suggested some other ideas. For example, it recommended to “have a clown or a fairy-story character carry a battery-operated radio playing around the streets, with appropriate signs. Thousands of people don’t yet know there is such a radio.” If the clown didn’t work out, the magazine suggested having a man with a battery-operated portable meet all he trains, or lending a radio to prominent people in the community and taking their picture.