A year before the Cuban Missile Crisis, the September 15, 1961, issue of Life magazine carried a big section of civil defense advice to the nation, along with a letter to the American people from President Kennedy. He stated that war couldn’t solve any of the world’s problems, but that the decision was not ours alone.

A year before the Cuban Missile Crisis, the September 15, 1961, issue of Life magazine carried a big section of civil defense advice to the nation, along with a letter to the American people from President Kennedy. He stated that war couldn’t solve any of the world’s problems, but that the decision was not ours alone.

Accordingly, he urged the magazine’s readers to carefully consider the issue’s contents to prepare for all eventualities. And the picture above shows how one family did exactly that by building one of the fallout shelters, the basic blueprints of which were included in the magazine. The magazine also told where you could write for more information, and it’s likely this family had done exactly that.

The view outside shows that this family’s town escaped the blast effects of the nuclear weapon, but the fallout had either arrived or was on the way. But life went on. Mom is tucking in the youngest child, while the older brother sits vigilantly near the entrance. (And the shelter did have an entrance, but since the original picture took up two pages in the magazine, it seems to have gotten cut off when the image from the two pages was combined). Meanwhile, the older sister seems to be fixing her hair, and the father is relaxing by lighting up a smoke in the relatively well ventilated enclosure. (In addition to the ventilation provided by the entryway, you can see four ventilation holes on the wall near the ping-pong table.)

The family shown in the picture below had even better protection, since their outdoor corrugated pipe shelter provided protection against the blast as well as fallout. In this case, instead of going inside the relax with a smoke, it looks like the father is hoping to catch a glimpse of the fireball before slamming the door before the blast wave arrives.

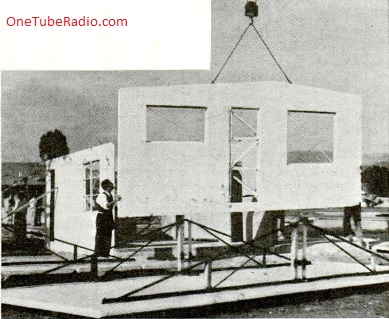

The magazine carried plans for more shelters along with estimates for their cost, as well as some other rudimentary civil defense instructions. It also suggested the possibilities for private community shelters, such as that constructed for the group shown below:

This shelter was in a suburb of Boise, Idaho. Families there incorporated and bought shares for $100 each for access to this community shelter dug into a hill. According to the magazine, the shelter had dormitories, a power plant, kitchen, hospital, and decontamination showers. In the photo, the families were lining up in peacetime to bring in their emergency rations.

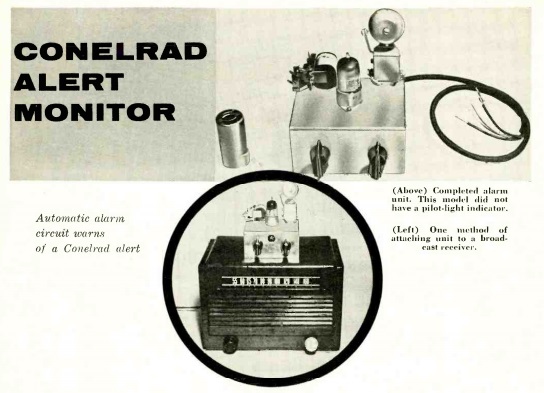

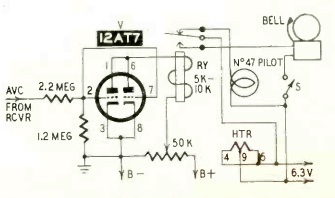

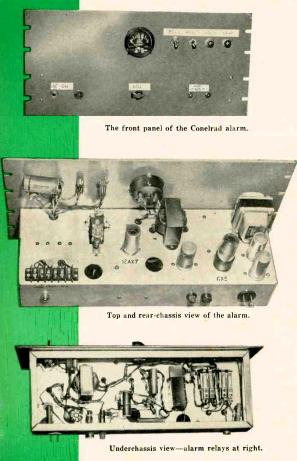

And speaking of peacetime, there was no reason to let all of that perfectly good living space go to waste just because Krushchev hadn’t hit the launch button yet, as demonstrated in the picture above of Amelia Wilson of Vega, Texas. The family had installed a shelter in the backyard, and Amelia seized upon the opportunity to make it her clubhouse and the perfect place to get away and chat with her friends. But as the magazine pointed out, the shelter was ready to be put to its intended use at a moments notice, as evidenced by the air blower directly above her and the exhaust pipe running out of the ceiling. And the radio entertains her now, but it’s also all ready to go at a moment’s notice to tune in civil defense information and warnings on CONELRAD.