Sixty years ago today, the Space Age started when the Soviet Union stunned the world by launching Sputnik 1, the Earth’s first artificial satellite, on October 4, 1957.

Soviet news agency TASS made the official announcement:

As a result of very intensive work by scientific research institutes and design bureaus the first artificial satellite in the world has been created. On October 4, 1957, this first satellite was successfully launched in the USSR. According to preliminary data, the carrier rocket has imparted to the satellite the required orbital velocity of about 8000 meters per second. At the present time the satellite is describing elliptical trajectories around the earth, and its flight can be observed in the rays of the rising and setting sun with the aid of very simple optical instruments (binoculars, telescopes, etc.).

In addition to reminding the West that the satellite could be seen by anyone, TASS went out of its way to make sure that even radio amateurs could hear for themselves that the Soviets had won the race into space. The official press release included Sputnik’s frequencies:

It is equipped with two radio transmitters continuously emitting signals at frequencies of 20.005 and 40.002 megacycles per second (wave lengths of about 15 and 7.5 meters, respectively). The power of the transmitters ensures reliable reception of the signals by a broad range of radio amateurs. The signals have the form of telegraph pulses of about 0.3 second’s duration with a pause of the same duration. The signal of one frequency is sent during the pause in the signal of the other frequency.

Receivers for the 40 MHz signal would have been a rarity, but thousands of hams and SWL’s had receivers that would easily tune 20 MHz. The frequency was cleverly picked to be close to WWV’s powerful 20 MHz signal. Thus, even though most receivers weren’t calibrated well enough to show the exact frequency, the U.S. National Bureau of Standards unwittingly made sure that everyone knew exactly where to tune.

In addition, the signal was so close to WWV, then at Beltsville, Maryland, that the unmodulated carrier from the satellite would create a heterodyne with WWV, allowing it to be heard even if the receiver was a simple one without a BFO.

The national association of amateur radio operators, ARRL, was flooded with calls from reporters. They gave instructions to listeners to “tune in 20 megacycles sharply, by the time signals, given on that frequency. Then tune to slightly higher frequencies. The ‘beep, beep’ sound of the satellite can be heard each time it rounds the globe.”

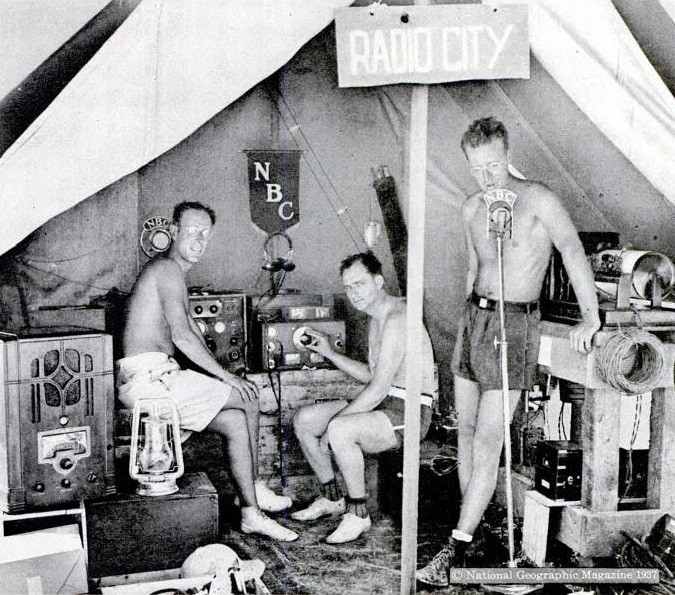

The December 1957 issue of QST included several photos of hams who had heard the satellite, And in many cases, those hams made the signal available to local broadcast stations and news outlets.

The December 1957 issue of QST included several photos of hams who had heard the satellite, And in many cases, those hams made the signal available to local broadcast stations and news outlets.

In Chicago, it was 27-year-old ham Jerome Tannenbaum, W9JJN, of 5240 Harper Avenue. He was described in the October 5 Chicago Tribune as the owner of an electronic engineering consulting firm and radio operator since he was 15. He told the newspaper that he heard a steady stream of “dahs” on 20.005, and definitely believed that the signal was from Sputnik, based upon the fact that it faded out right when predicted.

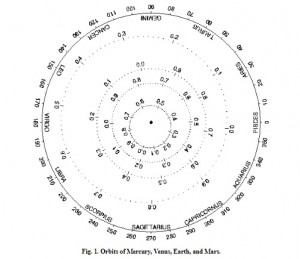

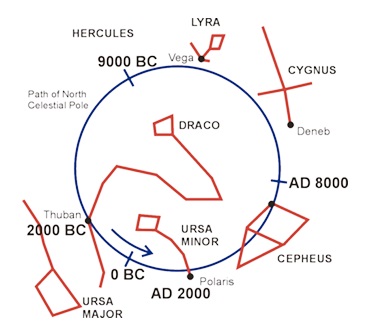

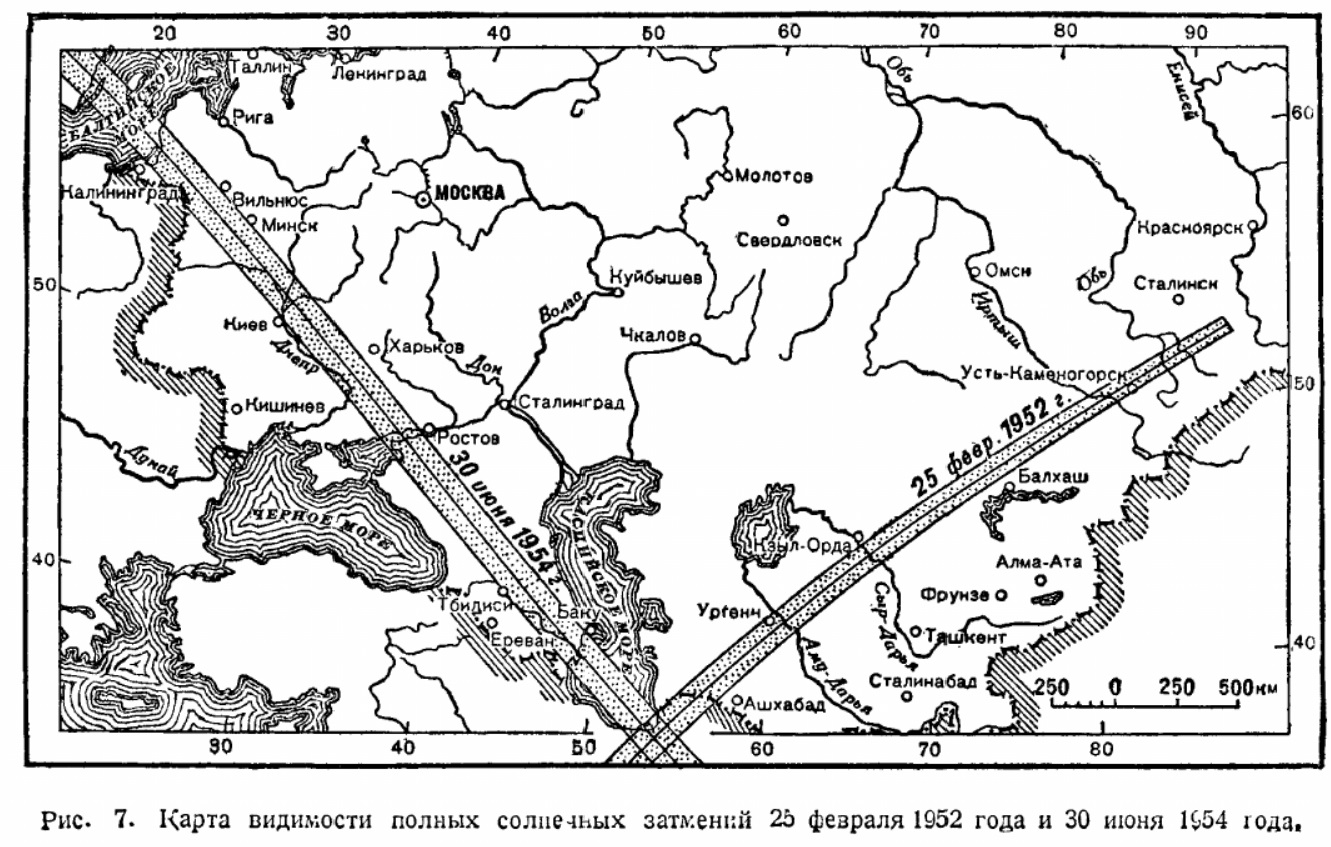

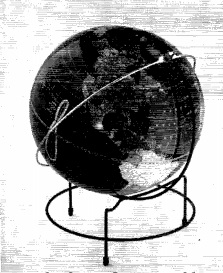

Hams quickly figured out how to track the orbit and predict the next time the satellite would be in range. Again, Moscow made sure they knew Sputnik’s orbital inclination of 65 degrees, and orbital period of 1 hour 35 minutes, by including this information in the first announcement. The simple locating device shown here was made at ARRL headquarters, merely by mounting a loop of wire around a globe. Once the satellite was heard, it was a simple matter of predicting where it would be heard next by rotating the Earth 23.75 degrees, the amount it would move during one orbit.

Apparently, Sputnik had at least one deliberate QRM’er. A letter in the December 1957 issue of QST reports that someone showed up on 20.005 MHz on October 7 with commentary such as, “this is the moon speaking,” sending the safety signal, and signing the call sign UA3ABD. The letter writer, Dave Harris, K2RRH of Lyndhurst, N.J., hoped “that donkey realizes that he is on tapes all across the country.”

Sputnik 1 remained in orbit until January 4, 1958, having completed 1440 orbits of the Earth. When it re-entered the atmosphere, WWV played another role. Hams and others were already familiar with meteor scatter, the reflection of radio signals by the ionized gasses caused when a meteor enters the atmosphere. Scientists and hams correctly guessed that Sputnik would cause the same phenomenon on re-entry. As a convenient signal source, WWV was once again used, and as predicted, the WWV signal appeared or got louder as the satellite entered the atmosphere. With this data, it was possible to track the satellite’s location until it completely disintegrated in the atmosphere.

Thousands of Americans were able to see or hear Sputnik. In many cases, this sparked a lifelong interest in science, space, and/or radio. I asked some of the hams at QRZ.com to share there stories about their experiences. A number of hams posted there or e-mailed their recollections.

Glen Zook, K9STH, currently of Richardson, Texas, shared this story of hearing Sputnik as a 13 year old in LaPorte, Indiana, and he gave me permission to include it here:

Hallicrafters S-40

There was a garage shop TV repair facility about a block south of my parents’ house. When Sputnik was launched and was operating, the frequency, 20.005 MHz, and the expected times when the satellite could be heard, were published in the LaPorte Herald Argus newspaper. Orville Hartle, the owner of the TV shop, had a Hallicrafters S-40 receiver and invited my father to come down and listen to Sputnik. I “tagged along” with my father.

As the expected time for the satellite to become in range, Orville started “fiddling” with the receiver. Nothing was heard! Finally, the “beep, beep, beep” from the satellite’s transmitter came faintly from the S-40’s receiver. Today, such a happening would be “ho hum”. However, in 1957 this was very exciting if, for no other reason, that the signal could be received by “Joe Blow” and not just by a very sophisticated scientific or military installation.

The repercussions from this evening, at least in my personal life, were great. Orville discovered that I had a serious interest in electronics which his son, who was about a year younger than I, had absolutely no interest. In fact, his son had very little interest in anything! Orville was an unusual character! He was a graduate EE but worked in the “tool crib” at the local Allis Chalmers plant, ran the TV shop evenings and weekends, and wrote books!

Orville started giving me as many old television chassis that I could “haul off” for the purpose of stripping for parts. I would take my sister’s “little red wagon” (she is 7-years younger than I) down to the TV shop and Orville would put 2, or 3, chassis in the wagon and I would bring them to my house. There were outside stairs to the basement and I would carry the chassis down and put them next to a workbench that my father had built next to the coal bin. My “experiments” were conducted, primarily, on that bench.

Thinking back, I cannot help but believe that Orville was a contributing factor to the fact that for Christmas, 1957, my parents bought me a used Heath AR-3 receiver (from Allied Radio Company in Chicago). Prior to that Christmas, I had been using an old TrueTone (Western Auto private brand) receiver with a shortwave band.

He was not an amateur radio operator, but he did encourage me to experiment with electronics and even gave me a television set, for my room, that was better than the one in my parent’s living room!

With the help of Dave Osborn, K9BPV, I passed my Novice Class examinations on my 15th birthday, 13 February 1959. It took over 3-months for the license to arrive in the mail. The license is dated 15 May 1959 but took an additional almost 2-weeks to come in the mail. I was just ending my freshman year in high school. In October, I took my General Class examinations at the FCC office in Chicago.

Then, in August 1962, between my senior year in high school and my freshman year in college, I took the examinations for my commercial radiotelephone operator’s license. My junior year at Georgia Tech, I got married and also got a job at the Motorola Service Station in Atlanta, Georgia. My senior year, I was hired directly by Motorola to establish, and then manage, the first Motorola owned portable / pager repair facility away from the Schamburg, Illinois, plant. After graduating, I was employed by the Collins Radio Company at the “new” corporate headquarters here in Richardson, Texas, and the “rest is history”!

All of this starting with the listening to Sputnik in October 1957!

Jim Allen, W6OGC, of New Braunfels, Texas, sent this account, which I share with his permission:

Sputnik went up in October, 1957, and lasted something like 3 months

One evening as we sat eating supper, the telephone rang. My dad got up and answered. He recognized the caller, the Superintendent of Schools, then became as flustered as I ever saw him. “Why, yes, he’s here. I’ll get him.”

He gestured to me, I got up and answered the phone. My dad hovered around with a look in his face, “there better be a heck of a good story for this!” He could not imagine why this big shot was calling for me, a 6th grader.

The Super, W5FFE, said to me, “listen to this.” I heard the beep, beep, beep, that no one had ever heard before. He explained it was a satellite, the first one, and he was listening to it on his radio, an SX-100 as I knew. I had been watching the launches from Florida, none successful thus far.

A few of us had been going to Novice classes, he knew of it, and had called some of us, each pass.

I don’t think my dad ever forgot that.

One surprise for me was the number of hams (and other members of the public) who saw Sputnik with their eyes. A number of such reminiscences were posted, although many of the viewers realized years later that they probably hadn’t seen Sputnik itself, but rather the larger covers that had been jettisoned from the smaller satellite. But still, they were watching with their own eyes something the Soviets had put into orbit.

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise that so many people saw Sputnik (or the other parts of the spacecraft). Today, when randomly stargazing, it’s not uncommon to see an artificial satellite cross the sky. After all, there are thousands of them, and just by randomly looking up, you’re bound to eventually see one. In fact, it’s almost mundane. When I was growing up in the mid-sixties, it wasn’t uncommon for my parents to point one out to me. It was already mundane, but there they were for all the world to see. It did strike me as amazing.

I remember reading about the Lykov family, who, starting in 1936, lived in complete isolation from society in Siberia for 42 years. According to one account, They had noticed starting in the 1950’s that “the stars began to go quickly across the sky.” The father, Karp Lykov, surmised that “people have thought something up and are sending out fires that are very like stars.”

When Sputnik 1 went up, it wasn’t mundane, and the predicted times of orbits were published in newspapers. Millions of people were looking up, expecting it. It shouldn’t have surprised me that so many of them still remember.

A hundred years ago this month, the April 1919 issue of Popular Science carried this image of a hypothetical traveler to the moon. The accompanying article detailed the problems of getting there. For example, balloons or airplanes were out of the question, since they both relied upon the atmosphere for their lift. A gun was a theoretical possibility, but the article pointed out that the Earth’s escape velocity was 26,000 feet per second. But the most powerful gun at the time had a velocity of only 5500 feet per second. The article correctly predicted, however, that there was a “ray of hope in the sky-rocket.” The article reminded readers that, contrary to popular perception, a rocket did not rely upon pushing against the atmosphere. Therefore, it would work in space.

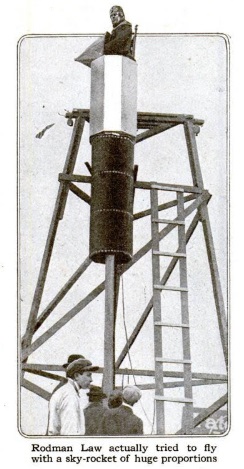

A hundred years ago this month, the April 1919 issue of Popular Science carried this image of a hypothetical traveler to the moon. The accompanying article detailed the problems of getting there. For example, balloons or airplanes were out of the question, since they both relied upon the atmosphere for their lift. A gun was a theoretical possibility, but the article pointed out that the Earth’s escape velocity was 26,000 feet per second. But the most powerful gun at the time had a velocity of only 5500 feet per second. The article correctly predicted, however, that there was a “ray of hope in the sky-rocket.” The article reminded readers that, contrary to popular perception, a rocket did not rely upon pushing against the atmosphere. Therefore, it would work in space. Robert Goddard had already begun his experiments, but his name was not known in 1919. The only rocketeer mentioned in the article was stuntman Rodman Law, shown at left boarding a rocket for a test flight. The article notes that the flight was a spectacular failure, although Law survived. Ironically, Law died later in 1919 of tuberculosis.

Robert Goddard had already begun his experiments, but his name was not known in 1919. The only rocketeer mentioned in the article was stuntman Rodman Law, shown at left boarding a rocket for a test flight. The article notes that the flight was a spectacular failure, although Law survived. Ironically, Law died later in 1919 of tuberculosis.

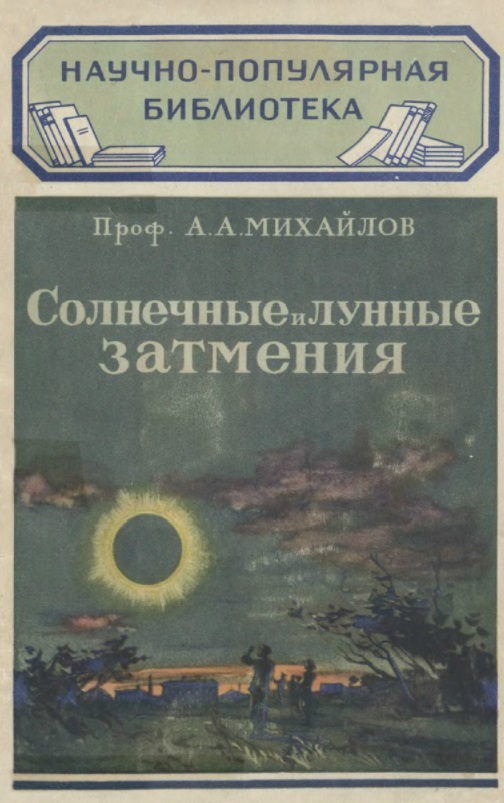

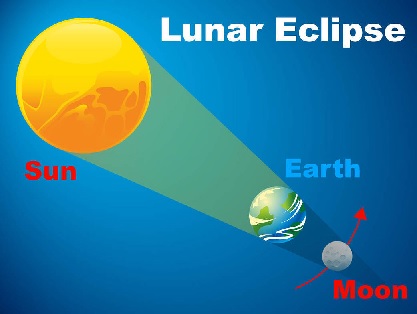

Even though the eclipse is full, the moon does not become fully dark. This is because the moon is illuminated by a ring surrounding the earth, namely, all of the sunrises and sunsets taking place on earth.

Even though the eclipse is full, the moon does not become fully dark. This is because the moon is illuminated by a ring surrounding the earth, namely, all of the sunrises and sunsets taking place on earth.