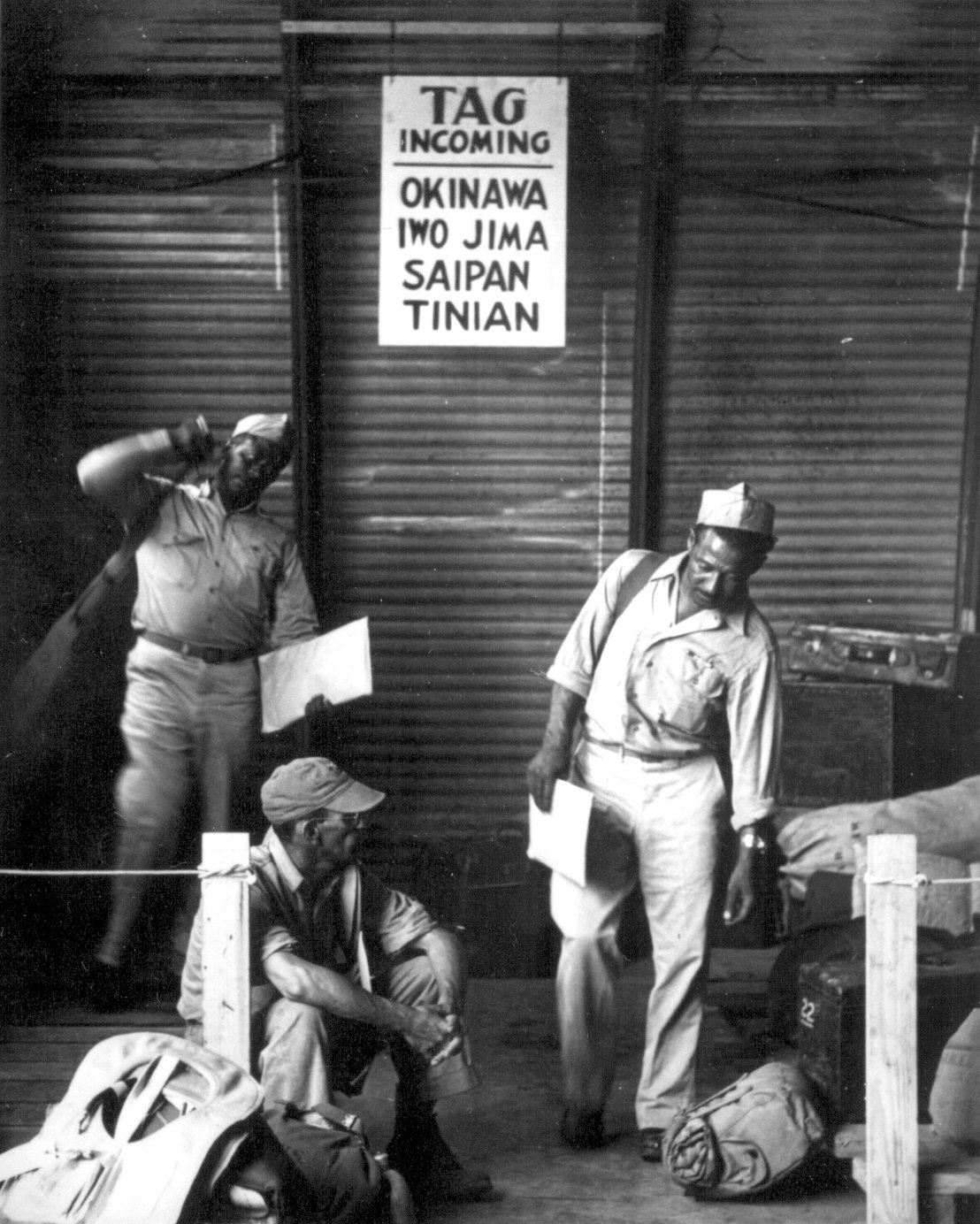

African-American soldiers preparing to fight the Japanese. US Gov’t photo.

Most Americans believe that Axis propaganda during World War 2 was basically unsuccessful, since America and the Allies relied on truth, whereas the Axis relied on deception. I generally take this same view, but as with many oversimplifications, it is not entirely true. An interesting article detailing a Japanese propaganda campaign that was somewhat successful can be found in a scholarly journal, the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Volume 19, Number 1, March, 1999. The article, by Sato Masaharu of Shobi University and Barak Kushner of Princeton University, is entitled “Negro Propaganda Operations: Japan’s short-wave radio broadcasts for World War II Black Americans.” It’s not available free anywhere online, but it is available at most University libraries, and your public library should be able to obtain a copy by interlibrary loan. The article is a look at a Japanese propaganda operation that did have a measure of success.

The authors concede that the Japanese campaign was by no means successful in the sense that any appreciable number of African Americans were swayed to the Axis side. But the existence of such propaganda, largely based upon truth, did force the United States Government to confront those realities. Some groups, such as the NAACP, used this propaganda as a tool, even though quick to concede that it couldn’t simply be accepted at face value.

In addition, the Japanese propaganda was successful to some extent in diverting U.S. Government resources to unproductive use. During the War, almost all African-American newspapers were investigated by the FBI. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, in part because of the existence of the Japanese propaganda, was convinced that these newspapers were disloyal.

Some Americans were also convinced that the Japanese were responsible for racial agitation. An officer stationed in Little Rock complained to the War Department that the “Negroes of Little Rock were being organized and incited by the Japanese.” There was, of course, no evidence that any such Japanese agitation had occurred, but that didn’t stop the belief, which was in part fueled by the Japanese propaganda.

African-Americans, like other Americans, were well aware of what the Japanese had been doing in China. W.E.B. DuBois, for example, who provided a certain amount of overt support for the Japanese propaganda, opined: “It is not that I sympathize with China less but that I hate white European and American propaganda, theft and insult more. I believe in Asia for the Asiatics and despite the hell of war and the fascism of capital, I see in Japan the best agent for this end.”

Black Americans were also cognizant of the fact that Japan had been on our side in the First World War, and had brought to the table at Versailles matters of racial equality. These concerns were quickly brushed aside by President Woodrow Wilson, who was in very many ways a typical Democrat racist, who had segregated the Army. White Americans were generally not cognizant of this, but African Americans were. So there was a certain amount of natural sympathy on which the Japanese could play.

The U.S. military was certainly aware of this image problem, and was doing its best to counter it. For example, in 1944, it released the film, The Negro Soldier, produced by Frank Capra, which is available on YouTube.

The focus of Japanese broadcasts was that only Japanese victory could ensure Blacks of the elimination of racial discrimination. To reach this conclusion, the Japanese broadcast largely true accounts of discrimination, violence, and even lynchings. In addition, comparisons were frequently made between Japanese leaders and African Americans such as Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington.

Throughout the war, Japanese embassies in neutral countries were tasked with researching American news for items of interest regarding discrimination against Blacks, and this news made up much of Tokyo’s propaganda content.

An additional source of program material came in the form of African-American POW’s, and there were plans in place to include them in programs discussing discriminatory conditions in American civilian and military life, reactions to conditions supposedly prevailing in Japan, and the humane manner in which Black POW’s were supposedly treated by the Japanese.

The first POW broadcast took place on December 2, 1943, during the Hi No Maru Hour program, which was beamed to America on short wave. It’s unclear whether any actual POW’s appeared on the program, or whether they were African American. But they were passed off as being POW’s.

POW’s were “encouraged” to take part in these broadcasts, and the Japanese pointed out that “we do not guarantee the life of those who refuse to cooperate.” Some prisoners did cooperate, and were tried after the War for doing so. They were able to point to this portion of the order to demonstrate that they had done so only under duress.

Unfortunately, as might be expected from a scholarly article of this type, the authors do not go into any detail as to the details of the broadcasts or the extent to which they were heard. It does note that the U.S. Government extensively monitored them, but it doesn’t address the critical question of how many Americans–Black or otherwise–actually listened to them.

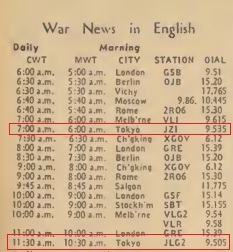

But the Axis stations were easy to hear by anyone in the U.S. with a short wave receiver. I’ve noticed that the short wave listings in many American newspapers stopped carrying listings of Axis stations after the U.S. joined the war. But the clipping here, from the February 1943 issue of Radio Guide, clearly shows the times and frequencies of English broadcasts from Tokyo.

But the Axis stations were easy to hear by anyone in the U.S. with a short wave receiver. I’ve noticed that the short wave listings in many American newspapers stopped carrying listings of Axis stations after the U.S. joined the war. But the clipping here, from the February 1943 issue of Radio Guide, clearly shows the times and frequencies of English broadcasts from Tokyo.

Despite the lack of information that the SWL historian might like to see, this article is an interesting look at the program content during the war, and it does a good job of refuting the notion that Japanese propaganda was ineffective. The article is extensively footnoted, and those wishing to learn more about this forgotten chapter in war history will have many sources available.

For more history of radio and short wave listening during the war, please see the following earlier posts:

- SW Broadcast Bands During WW2

- WW2 Short Wave Listening

- Prisoner of War Broadcasts

- German and British Amateur Radio During the War

- Radio Coverage of Pearl Harbor

- The US Embassy in Tokyo After Pearl Harbor

Click Here For Today’s Ripley’s Believe It Or Not Cartoon

![]()

Brings back unpleasant memories…

Pingback: American Shortwave Broadcasting, 1941 | OneTubeRadio.com